In case you haven’t noticed, a technological revolution is unfolding before our very eyes. It may feel like it snuck up on us, but it’s been around for a while.

I’m talking about the rise of artificial intelligence (AI), which could become one of the most transformative and disruptive technologies of all time, perhaps even more so than the Internet.

It also raises some significant safety, moral, and ethical issues. As Elon Musk warned at MIT’s AeroAstro Centennial Symposium, “I mean with artificial intelligence, we’re summoning the demon.”

This is the first of two articles about AI. In this one, I’ll give you an overview (which will help if you’d like to become more familiar with it) and also touch on some of the moral and ethical concerns that Christians and others (rightly) raise.

In the second part, I’ll discuss some of its implications for planning and living in retirement. Will it help or hurt retirees and older people in general?

What is it, anyway?

If AI seems like science fiction becoming nonfiction, in many ways, it is. And for many of us, it’s a mystery, a high-tech “black box.”

So, what exactly is AI?

I must state that although I spent nearly 30 years of my professional life in information technology (IT), I was never involved in any AI projects.

While I have some understanding of the underlying technologies (because they’ve been around for a while), I’m no expert.

Furthermore, I’ve gleaned what I know about it from others I have read and studied.

A big challenge in getting our heads around AI is that it’s so new and advancing so quickly. As Eliezer Yudkowsky, founder of the Machine Learning Research Institute, said:

“By far, the greatest danger of Artificial Intelligence is that people conclude too early that they understand it.”

AI is basically about computers performing human-like tasks, such as understanding language, playing chess, making decisions, being creative, or having conversations.

If that seems relatively non-threatening and benign, that’s because most of these computerized functions are. AI is advanced technology designed to simulate human intelligence applied to specific problems or situations.

“Simulate” is the key—it’s artificial intelligence. It may eventually emulate human reason and intelligence or even replicate them almost perfectly (and some would suggest far surpassing them), but it’s not human and never will be.

That’s because it will never be able to replicate the metaphysical aspects of human beings—the ‘spiritual,’ if you prefer. A computer may have rules programmed into it, but it doesn’t have morals, ethics, beliefs, or faith that together comprise a human heart, nor does it have a “living soul.”

A computer may have incredible analytical power, but it can’t be a “living creature” the way man is (Gen. 2:7). A machine can’t reproduce the image of the Creator because it wasn’t made in that image; it can only create a partial image of a human who is an image of God.

Still, there’s no doubt that AI is developing so rapidly that the day will come when there will be little discernible difference between human intelligence and artificial intelligence. This raises huge ethical and moral questions I’ll discuss later.

Based on the definition above, the chat service you encounter on a customer service website that doesn’t involve a human (unless you specifically request one) is an early version of AI called a “chatbot.”

And companies are using them extensively.

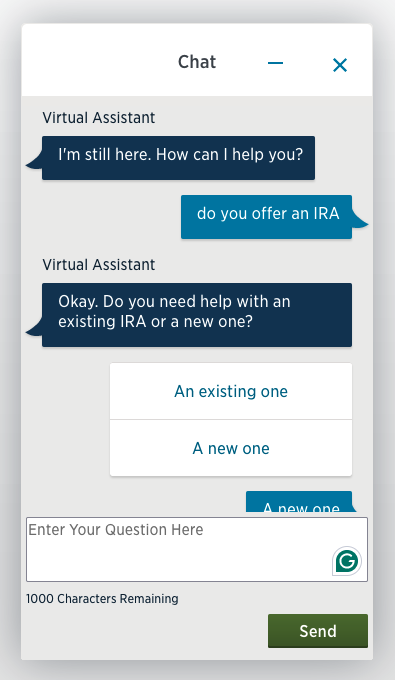

For example, when I log in to my insurance company’s website, usaa.com, I see “chat” in the top navigation bar. After clicking it and exchanging some human-like pleasantries with the “virtual assistant,” I ask a question I already knew the answer to: “Do you offer an IRA?”

The chatbot replies, “New or existing?”

That’s an odd answer since “existing” as an answer to “Do you offer an IRA?” is a bit inconsistent with the question. I chose “new.” The chatbot responded, “I can help direct you to the right place for information about IRAs.”

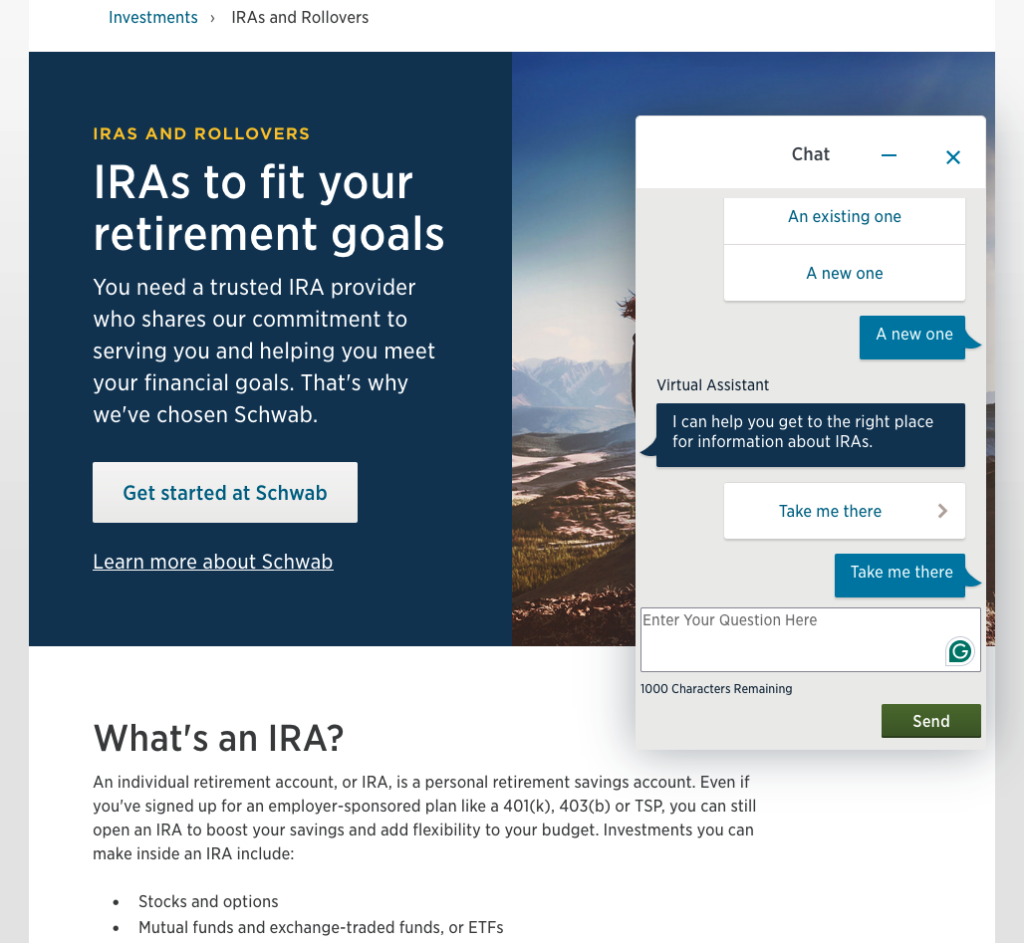

Okay, fair enough. It then asked if I wanted it to “take me there.” I clicked on the “take me there” tab. It took me to a USAA page with a link to Schwab Investments, which became USAA’s “trusted investment advisor” after USAA sold its investment management company to them a few years ago. (I already knew that, which is why I was asking about an IRA.)

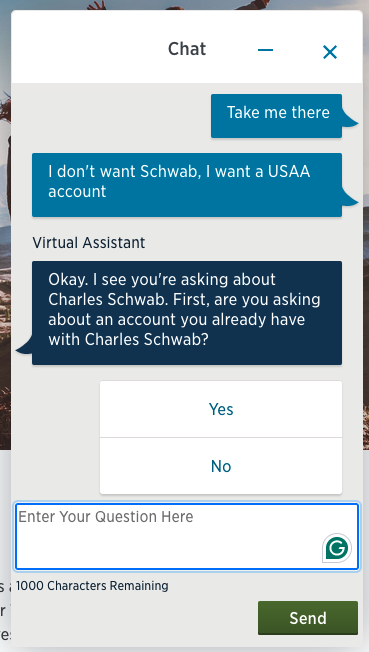

Then I threw the chatbot a bit of a curveball (demonstrating a weakness of these early AI implementations); I told it I didn’t want a Schwab account; I wanted to open a USAA IRA.

It responded, “Okay. I see you’re asking about Charles Schwab.

This weak response missed my point – it just picked up on the keyword “Schwab.”

It then asked if I was asking about an account I already had with Charles Schwab, giving me “yes” and “no” tabs to choose from. The chatbot couldn’t interpret precisely what I was saying or looking for and respond accordingly.

But I played along anyway:

- Me: “No”

- Chatbot: “I can help you get to the right place to learn about your investment options.”

- Me: “I want to stay with USAA.”

- Chatbot: “Sure. You can add an outside account on usaa.com. Just so you know, we need to verify ownership of any external accounts you have, which can take up to three business days.” (This refers to USAA’s account aggregation feature, which most large financial companies offer.)

- The chatbot displays: “I want to add an account now,” so I can choose to do so or not.

- Me: I typed, “I want to open a new IRA at USAA, not Schwab.”

- Chatbot: “I found the following information that may be helpful.”

- Chatbot displayed two tabs: “I have a question about Schwab” and “I have a question about IRAs.”

- Me: I typed, “I want a USAA IRA.”

At that point, the chatbot shut down and took me to my member login page. It had had enough of me.

So what’s going on here? It seemed odd that at some point, the chatbot didn’t say, “USAA no longer offers IRAs, but we recommend you open one with our trusted partner, Schwab Investments.”

But chatbots use predefined patterns they’ve learned to respond to everyday questions and inquiries; there’s not much room for nuance or over-complication. My experience with the USAA implementation illustrates this.

If I’d asked the USAA chatbot about my homeowner’s insurance policy or my Medicare supplemental plan, I’m sure the experience would have been very different. It would have been more like communicating with a live person instead of a chatbot.

Chatbots’ limitations lie in how AI large language models (LLMs) work.

LLMs use a lot of computing power (which is very good for the computer industry) to read and process vast amounts of text to determine the structure of language based on probabilities.

So they do not think; they calculate. They’re not intuitive; they’re predictive. These early implementations have limitations, but they are improving rapidly.

Large language models (LLMs)

The earliest chatbots date back to the 1960s. However, conversational AI emerged in the early 2010s. It used advanced natural language processing (NLP) and machine learning (ML) algorithms to understand natural language more accurately than early rule-based bots.

Early conversational AI implementations went beyond keyword matching and learned from previous user interactions (the “machine learning” component), providing more personalized assistance and thus becoming more human-like.

However, the big problem with traditional AI-based chatbots is that they need help understanding the nuances of human language and maintaining contextual awareness. This was exemplified in my chat with the USAA chatbot—it got part of it right but ultimately missed the essence of my request.

LLMs can ‘get it,’ but they don’t ‘get it’ the way humans do. They’re super fancy autocomplete features that guess what’s coming next based on statistics rather than logic, which can lead to mistakes.

For example, consider the basic everyday AI feature that many people use: smartphone autocomplete. I was recently at a wedding rehearsal dinner, and the maid of honor joked that her phone’s autocomplete referred to her as the “maid of horror” in a text to one of her friends.

This may be funny in some social situations, but these models can sometimes generate responses that sound correct but are entirely made up. This has real-world implications, such as when lawyers used them to create fake legal opinions that resulted in fines from a federal judge.

However, Chat GPT, one of the most popular AI-powered LLM chatbots, has received considerable attention for its ability to engage in natural language conversations, generating responses that often mimic human speech patterns with amazing accuracy.

Still, Chat GPT can confuse or miss the context of a question, but it usually responds reasonably, even if it doesn’t have an exact answer.

For example, I asked, “What is the airspeed velocity of an unladen swallow?” (This is a line from the “Bridge of Death” scene in Monty Python and the Holy Grail. Watch the whole scene for a good laugh if you appreciate their humor.)

ChatGPT replied,

“The airspeed velocity of an unladen swallow is a reference to a joke from the movie ‘Monty Python and the Holy Grail.’ In the film, it’s a question asked by King Arthur to a bridgekeeper as part of a series of questions to pass over a bridge. The specific speed is not given, and the joke is more about the absurdity of the question itself. However, some fans have humorously calculated various estimates based on bird species and aerodynamics, but it’s all in jest.”

I then gave it some more information (from later in the same scene): “What if I told you it is an African swallow?” To which it replied,

“Ah, if you’re referring to an African swallow, then the response would typically involve further Monty Python references. In the movie, when King Arthur asks about the airspeed velocity of an unladen swallow, the bridgekeeper responds by asking whether he’s referring to an African or European swallow. This leads to a humorous exchange about the migratory patterns of swallows and the limitations of carrying coconuts.”

I didn’t expect a straight answer, and it was fun to ask the questions. The chatbot’s answers were pretty good.

Despite their limitations, LLMs are revolutionizing many industries by increasing productivity and efficiency. Think education, music, law, medicine, finance—you name it. (We’ll return to this in the next article on AI and retirees.)

But it’s important to remember that LLMs are not the same as Artificial General Intelligence (AGI), which would be more like human reasoning rather than just predicting words and responses. AGI is the next big frontier and potentially the most impactful (and risky) form of AI.

At the very least, it will pose ethical and moral problems and dilemmas greater than any IT advancement to date.

The risks of artificial general intelligence (AGI)

There’s a considerable debate about when AGI will become a reality. The other more critical discussion is whether it will be good for us.

Some experts say it’s a long way off, while others think it could happen in our lifetime. There is also and will be much disagreement about whether AI will be good for us.

It can be very easy to get excited about the possibilities of AI without considering all the issues and risks involved. I agree with Joe Carter, who wrote this in his article on AI for The Gospel Coalition:

“Christians need to be prepared to maximize the benefits of such technology, take the lead on the question of machine morality, and help to limit and eliminate the possible dangers.”

While we’re still a long way from AGI, LLMs are already causing concern. Mastering language is a big deal for humans, and whoever controls language holds significant power over humanity.

For example, AI could be used to create deepfake videos or manipulate online conversations, raising concerns about misinformation and manipulation. This has already happened to a significant degree, and there’s no reason to believe it won’t continue.

There are also many other ethical and societal considerations. The use of AI in decision-making processes, from credit scoring to hiring practices, raises concerns about algorithmic bias and discrimination.

In addition, given the likelihood that AI will replace many jobs currently performed by humans, it poses an economic threat to certain groups and may disrupt traditional employment models.

While AI offers exciting possibilities, it’s important to understand its limitations and potential risks as we navigate this rapidly evolving technology landscape. Like any new technology, it has the potential to be used for nefarious purposes, not because the technology is intrinsically evil but because it’s in the hands of fallen creatures who can be tempted to use it for evil purposes.

We must remain vigilant about the risks and challenges of unchecked AI development. Concerns about privacy, cybersecurity, and algorithmic accountability loom large, necessitating robust regulatory frameworks and ethical guidelines to protect against the misuse and abuse of AI technologies.

Can AI make us “gods”?

We also need to think deeply about the spiritual implications of AI precisely because it has the potential to be such a game changer.

Some would go so far as to suggest that it has the potential to make us “gods.” Anthony Levandowski, a Silicon Valley engineer of self-driving cars fame, said of the future of AI,

“What is going to be created will effectively be a god,” . . . “It’s not a god in the sense that it makes lightning or causes hurricanes. But if there is something a billion times smarter than the smartest human, what else are you going to call it?”

In his book Digital Liturgies, Samuel James writes extensively about the intersection of technology and the Christian life and describes the utopian “technology–as—salvation” worldview.

Here, he describes what may be the ultimate vision that some have for AI:

“…. the notion of the “Singularity,” an eschatological belief that eventually human consciousness and technology will merge and form a new era in human existence.”

pp.16

That sounds like something out of a Star Trek movie. What he’s referring to is “transhumanism,” a word I had never heard or read before, but which is,

“. . . the idea that technology will “successfully” splice human beings from their bodily limitations and usher in a techno-paradise. Transhumanism refers to a broad set of beliefs and ideas about the future of human-machine singularity. Transhuman philosophy, far from being a foil in science fiction novels or a theoretical “slippery slope,” is rather a live worldview among serious educators and inventors.”

pp. 16

Actually, to be ”transhuman” is more of an intermediate state toward becoming ”posthuman.”

According to the website “What is Transhumanism?“, some believe that ongoing breakthroughs in various fields, like information technology, genomics, computational power, and pharmaceuticals, will offer humans the possibility of,

“. . . reaching intellectual heights as far above any current human genius as humans are above other primates; to be resistant to disease and impervious to aging; to have unlimited youth and vigor; to exercise control over their own desires, moods, and mental states; to be able to avoid feeling tired, hateful, or irritated about petty things; to have an increased capacity for pleasure, love, artistic appreciation, and serenity; to experience novel states of consciousness that current human brains cannot access.”

Posthumans could be fully synthetic artificial intelligence, or “enhanced uploads” (read: “AI”)—they could be the result of many smaller but cumulatively profound augmentations of a biological human.

So there you have it: A “posthuman” person has, by whatever means (presumably evolution, genetic engineering, and AI augmentation, or entirely “new creations”), found their “salvation.

We’re all looking for salvation somewhere, but we know there’s only one (Isa. 45:22-23).

Such a vision for technology in general, and AI in particular, has enormous implications for individuals and the world.

In his article for TGC, Joe Carter expresses concerns, shared by many others, about AI and its potential to act as “artificial moral agents” (AMAs) that may have ethical implications for humans, animals, or the environment.

These concerns manifest in various ways, such as implicit or explicit ethical agency in machines. For example, he notes how self-driving cars raise questions about how they should prioritize life in potential collision scenarios.

In addition, the influence of AI on human behavior is a significant concern. For example, AI-enhanced dolls and robots could potentially reduce empathy by promoting individual objectification.

Carter encourages Christians to approach AI with a framework rooted in biblical principles. He emphasizes the importance of maximizing benefits, addressing ethical dilemmas, and protecting human dignity.

However, this framework must also be based on God’s Word rather than cultural cues or government directives.

AI can’t image God

Christians believe that human beings are created in God’s image (Gen. 1:27). Therefore, we must distinguish between replicating human reason and intelligence through technology, which is possible, and replicating metaphysical human attributes such as ethics, purpose, compassion, and love, which is not.

This raises concerns about the potential dangers of a world dominated by AI (which is possible) without the constraints of metaphysical human attributes.

We need to understand the possible consequences of handing over societal control to AI, which could lead to the loss of human conscience and the devolution of humanity, even as AI technology itself evolves.

It is also possible that AI will exacerbate existing societal crises that are at least partially caused by advanced technology, including loneliness, mental health issues, addiction, and sexual degradation.

Christians can choose to use AI for good and wise purposes while resisting it as the only true path to human flourishing. Instead, Christians must point to our Creator’s wisdom and redemptive plan as that path (Ps. 25:4-10).

I am cautiously optimistic but also concerned

As I wrote in a previous article about blockchain, I am (or was) a technology guy who tends to be optimistic about promising new technologies.

This rapidly evolving technology can potentially improve almost every sector of the economy and society.

Still, it comes with perils that could be cataclysmic if we do not address them.

One area where AI impacts and will undoubtedly have an even more significant effect is retirement planning and living. We’ll look at that in the following article.

I hope this new tool will have enough “guardrails” to limit abuse. If we’re involved in its development, we can pray that society will use it to uphold human dignity, glorify God, and work toward that end (Isa. 43:7, 1 Cor. 10:31).