Many financial planners, advisors, and especially retirees are wary of annuities. They cite cost, complexity, loss of liquidity, under-performance, and other factors as their primary concerns. In many cases, their concerns are warranted.

Yet many retirement planning professionals, academics, actuaries, and economists—i.e., a bunch of really smart people—regularly encourage consumers to consider a particular type of annuity: the lifetime income annuity.

I am among those retirees who haven’t purchased a lifetime income annuity but have maintained a conservative, low-cost, diversified portfolio of (mostly) index funds to generate retirement income.

But I often wonder if I’m doing the right thing. Am I making an emotional decision or a fact-based, objective one? Am I being prudent or foolish? Why don’t I heed the advice of the “smart people” whispering in my ear?

Of course, not every retiree needs an annuity. Everyone’s situation is different; an annuity would better serve some than others.

I don’t think I absolutely need one, but it’s still possible I’d be better off with one. I’d have a larger “guaranteed” income floor, if nothing else.

Apart from not wanting to part with a large lump sum (probably part emotion), even though it will generate a “guaranteed” lifetime income stream, do I have rational reasons not to purchase one? Should I reconsider? Should you?

What’s the biggest thing that’s holding me back? Why am I reluctant?

One word: inflation.

Inflation is that thing

Inflation has existed for a long time. Scripture provides many examples of it being precipitated and exacerbated by war, disruption of supply chains, and sieges (lockdowns). Another contributing factor is greed and corruption, which can be price gouging, dishonest weights, measures, etc. (Deut. 25:13-15; Prov. 20:10, Ez. 45:10, Micah 6:10-11).

Understanding the impact of inflation on any retirement income strategy is crucial. That’s why I find income annuities generally less attractive than other options, like a TIPS ladder, which I’ve also considered and written about. (I haven’t pulled the trigger on that either; I invest in a TIPS index fund instead.)

It’s important to note that we’re currently experiencing relatively high inflation. In June 2022, U.S. inflation peaked at 8.9 percent, a dramatically high level after nearly three decades of fairly stable prices.

Although inflation is slowing, prices are still stubbornly high, and it isn’t easy to speculate where it might go. This uncertainty underscores the need for most retirees, including myself, to have some inflation protection in our portfolios, even if we can’t wholly inflation-proof them.

Most financial professionals and retirees assume some level of future inflation, perhaps in the 2 to 3 percent range. Since inflation recently reached that 40-year high of almost 9 percent, a return to 2 to 3 percent doesn’t sound too bad.

Periods of high inflation can hurt both retirees and non-retirees alike. The degree of impact largely depends on the extent to which income and investments keep pace with rising prices. (The amount of fixed versus variable rate debt can also be a significant factor.)

But remember—the damaging effects of inflation on retirees don’t just have to do with the inflation rate; they also include the duration. That’s because inflation, like interest, compounds itself.

To illustrate, let’s look at the last few years of inflation, beginning in 2020. An item costing $1.00 in 2020 now costs $1.22, a 22 percent cumulative inflation rate.

Thus, when someone says, “Inflation has averaged X% a year,” using the scenario above, they mean cumulative inflation divided by the number of years. The average annual inflation rate for 2020 to 2024 is 4.4%. But the actual yearly inflation rates are as follows:

- 2020: 1.4%

- 2021: 7.0%

- 2022: 6.5%

- 2023: 3.4%

- 2024: 3.5% (YTD)

If average annual inflation stays high and the CPI increases 22 percent over the next five years, we’ll need almost $1.50 to buy what $1.00 did in 2020. That’s a 50 percent cumulative increase over ten years!

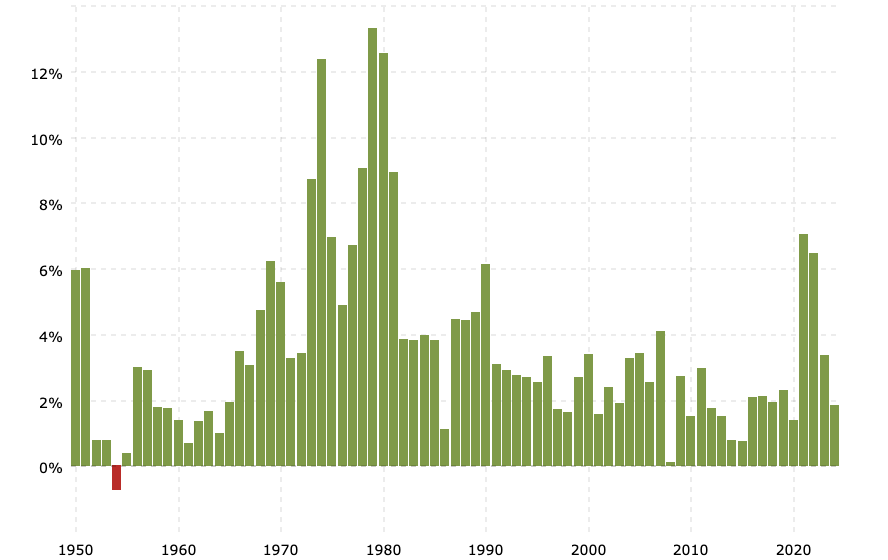

The chart below shows historical inflation by year since 1950:

Most years were in the 2 to 4 percent range, but there were periods, such as the 1950s and 60s and the 2000s and 201Xs, when inflation was lower than that, and others, like the 1970s and 80s, when it was much higher.

I can only laugh when a politician says, “Inflation is down 4 percent.” Yes, that may be true in that the current inflation growth rate is 4 percent less than it was at some point, but that doesn’t mean overall (cumulative) inflation up to that time is any less.

It also doesn’t mean that cumulative inflation isn’t still going higher—it only means that the rate at which it is rising has slowed down a little; in my example, 4% of whatever the current rate was. If it was 8%, current inflation slowed by (.04 * .08) = .032 (3.2%), and the new inflation rate is 4.8% (8.0% — 3.2% = 4.8%).

If we have 0 percent inflation in 2025 (not likely) and cumulative inflation is 25 percent for the 2000 through 2024 period, the cost of living will still be 25 percent higher than in 2020 and 3.5 percent higher than in 2023.

So, what can we do about this?

While inflation is beyond our control, wise investing can mitigate its effects. Fortunately, several types of investments have historically outperformed inflation, offering some help for retirees.

Your financial advisor can provide valuable guidance in navigating these investment options. If you prefer a more hands-on approach, I encourage you to read this article I wrote a while back. In either case, it’s crucial to fully comprehend the risks and trade-offs involved to make an informed decision.

Inflation and income annuities

That brings us back to annuities. In this case, I’m referring to one of two types of income annuities:

1) A nominal (no inflation protection) single premium income annuity (SPIA) and

2) A nominal income annuity with a 3 percent annual cost of living adjustment (COLA, not CPI-based).

There are no longer any “real” annuities with a cap adjusted annually for inflation based on the Consumer Price Index for all Urban Consumers (CPI-U). If there were, I would be more likely to purchase one with some of my retirement savings.

I’m not including other more costly and complex annuity types, such as variable or fixed index annuities. However, some contend that these offer inflation protection as they are tied to the stock market. (That’s a discussion for another article.)

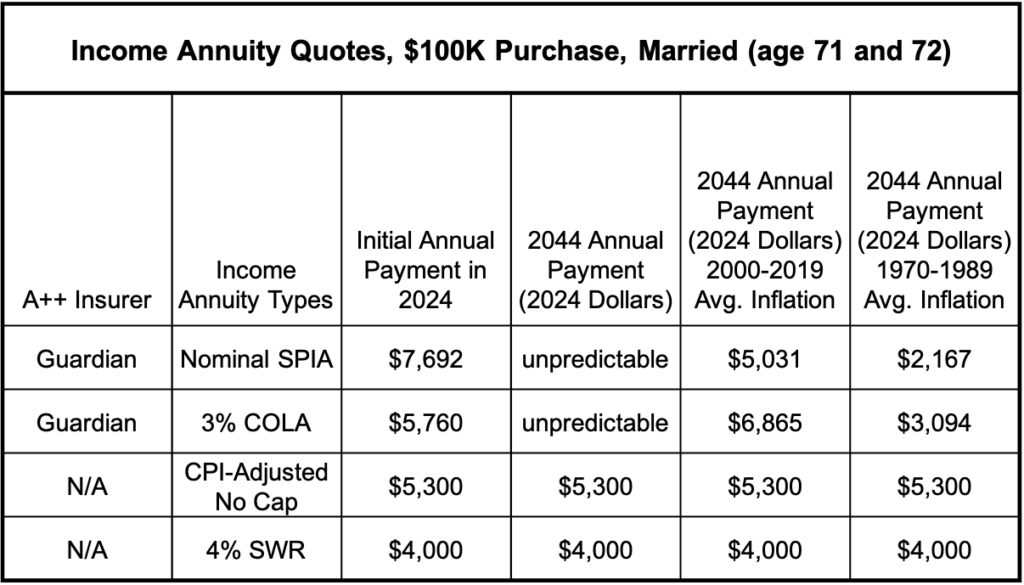

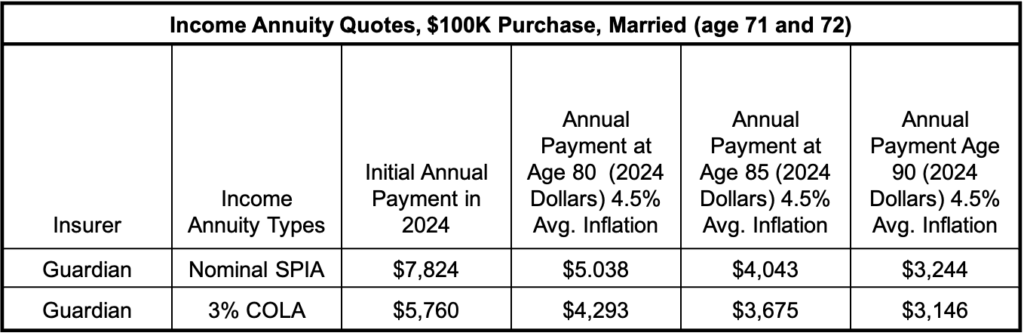

Here’s some analysis to illustrate inflation’s insidious effect on income annuities. Let’s say I wanted to use $100,000 of my retirement savings and purchase a lifetime income annuity for my wife and me.

I went to incomeannuities.com for quotes and chose a high-payout product from Guardian Life, an A++-rated insurance company. I also selected another product from Guardian, with an annual 3 percent adjustment for inflation (COLA), but the adjustment is fixed—it’s not based on actual CPI data.

I included a make-believe CPI-adjusted annuity (since they don’t exist) and added a standard 4% “safe withdrawal rate” (SWR) strategy for comparison purposes.

To complete the analysis, I calculated the future purchasing power of each option in today’s dollars, meaning I adjusted them for inflation based on two historical periods—one with very high inflation (1970s through 80s) and one with relatively low inflation (2000s through 2010s), a best- and worst-case scenario based on inflation history.

Notice how much higher the nominal SPIA annual payout of 7.7% is compared to the others. (Remember, the payout is a return of principal with some interest, plus “mortality credits.“) Assuming I’m willing to part with the $100K, it’s a no-brainer, right?

Maybe not. It’s not just the amount that matters (although the more, the better)—it’s purchasing power five, ten, twenty-five, or even thirty or more years later.

If I purchase the nominal SPIA, I have no idea how much purchasing power it will have in the future because I can’t predict future inflation. Its future purchasing power might be much more or less than what $7,692 can buy today in 2024.

(That said, 7.7% is a terrific payout percentage, likely boosted by the fact that my wife and I are in our 70s now, along with currently higher long-term bond interest rates that the insurance companies pool and invest annuity policy dollars in.)

I also can’t predict the purchasing power in 2024 dollars of the 3% COLA annuity in 2044 since inflation may average more or less than the 3 % annual adjustments.

However, I can predict the purchasing power of my “made-up” CPI-adjusted annuity and the 4% SWR strategy. Their purchasing power in today’s dollars remains the same no matter what inflation does because, theoretically, they’re both inflation-adjusted annually.

The two far-right columns show the purchasing power in today’s dollars 20 years in the future based on past inflation for different periods: low inflation from 2000 to 2020 and high inflation from 1970 to 1980 (refer back to the historical inflation by year chart above).

Not surprisingly, the real payout for the nominal SPIA is lower for both periods and dramatically lower for the high inflation period.

The 3% COLA annuity payout is higher for the low inflation period because the COLA adjustments were slightly higher than average inflation. However, the COLA annuity couldn’t keep up with inflation during the high inflation period, so the final payout was significantly lower.

Which annuity is better?

Which annuity will provide more lifetime purchasing power, the nominal annuity that pays $7,692 per year or the COLA annuity that pays $5,760?

That’s a trick question. The correct answer is that I can only know at the end of retirement. I have to guess about unpredictable future inflation rates to choose one over the other. And therein lies my problem.

Suppose future inflation resembles the 2000s and 201Xs, which had an average annual inflation of over 6%. In that case, the 3% COLA annuity will do better and purchase more in today’s annuity payout dollars than the nominal SPIA annuity.

On the other hand, if future inflation is historically high, as in the 1970s and the 1980s, both annuities pay out much less in today’s dollars than during low inflation. However, the 3% COLA annuity still does better because of the annual adjustments.

But suppose you had to purchase one or the other—which one would you pick? Both annuities carry inflation risk, although the COLA product mitigates it to an extent with the annual 3% adjustments.

However, that comes with a trade-off: the initial payout with that product is $1,932 less per year.

The idea behind annuities is to guarantee income for life. But I would prefer guaranteed purchasing power for life. Both products offer the former, but unfortunately, neither provides the latter.

Therefore, I’d struggle to choose either. But wouldn’t they still be better than the alternative, the SWR “risk-based” portfolio, which could significantly decimate any number of macroeconomic events, including inflation?

What about the SWR portfolio?

Two major but unpredictable variables impact an investment portfolio’s long-term viability when a 4% so-called “safe withdrawal rate” (SWR) strategy is used—annual inflation and returns.

With this strategy, you start out withdrawing 4%, adjusted annually for inflation, from your 60%s stocks/40% bonds portfolio. So, if inflation is 4% in year one, your new SWR is adjusted to 4.16% for year two. If it’s 6% the following year, you will change it to 4.41%, and so on.

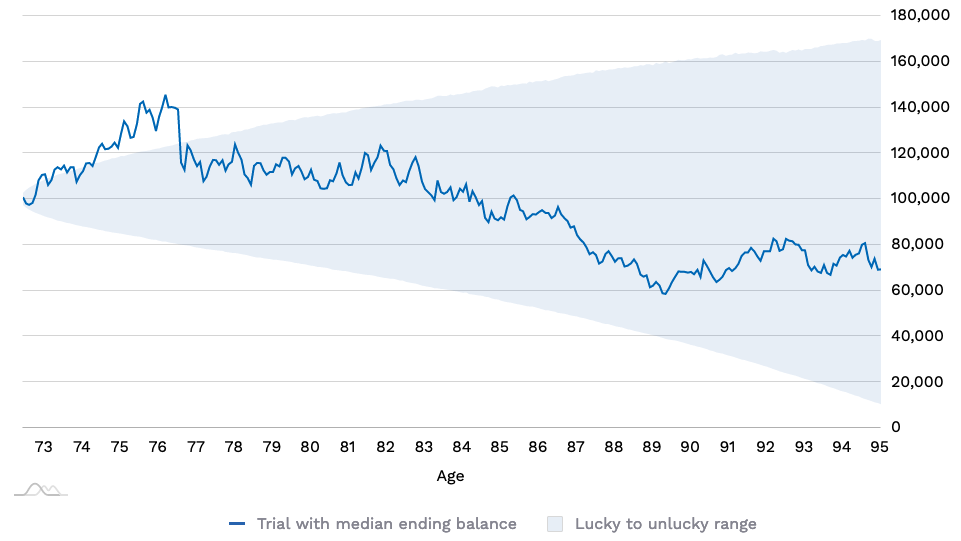

If inflation is lower than average and resembles the inflation of the 2000s and 201Xs, which had an average annual inflation of 2.1%, a 60/40 (balanced) stock and bond SWR portfolio would do very well based on the Monte Carlo planner tool analysis I ran on honestmath.com. Even at the 20th percentile, the portfolio would survive to age 95.

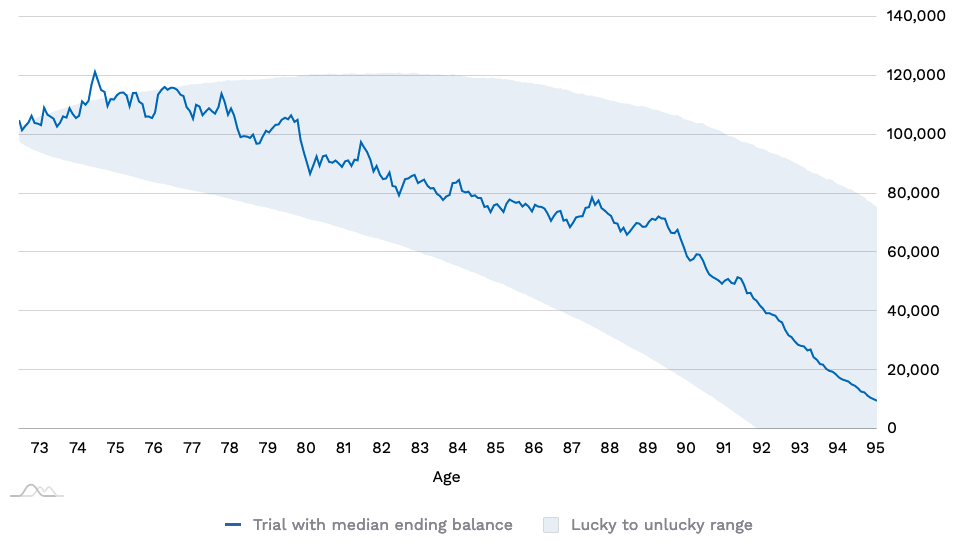

SWR Portfolio Balance Through Time—2.1% Average Annual Inflation

The analysis doesn’t change dramatically if the allocation is 40/60, which closely resembles my personal portfolio.

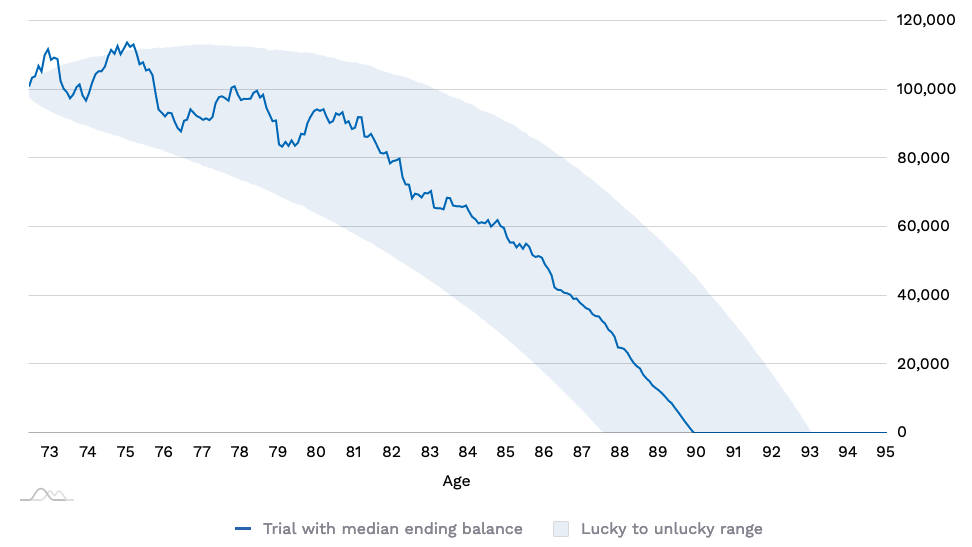

However, if inflation is high and mimics the high inflation of the 2000s and 201Xs, which had an average annual inflation of 6.54%, the 40/60 SWR portfolio would survive until age 90 at the median (50th percentile). And at the 20th percentile, it would be depleted by age 87.5. In the best-case scenario, the portfolio would last to age 93.

SWR Portfolio Balance Through Time—6.25% Average Annual Inflation

That’s why the SWR portfolio strategy is more risky than many think and why so many really smart people suggest we use some of that money to purchase an income annuity. It’s not just because of market risk, which we all tend to focus on, but also because of inflation and longevity risk.

I also ran a “what if inflation is higher than normal but not sky high” scenario with 4.5% average annual inflation. Based on a 40/60 portfolio that earns relatively conservative average annual returns of 6% and 3.5%, respectively, the SWR portfolio does better than we might expect.

SWR Portfolio Balance Through Time—4.5% Average Annual Inflation

In this scenario, the portfolio is depleted by the age of 92 at the 20th percentile, survives to age 95 at the 50th, and has a remaining balance of almost $80,000 at the 80th percentile. It’s not too shabby, but remember, none of this is ‘guaranteed.’

I also ran the numbers for the two income annuities at an average annual inflation rate of 4.5%. As you might expect, the COLA annuity does pretty well, but the nominal SPIA gets hit hard, even after the first nine years (when I would be age 80).

The annuities pay nearly the same amount in inflation-adjusted dollars at age 90, but the cumulative payout favors the nominal SPIA.

Is a TIPS Ladder a better choice?

I mentioned TIPS (Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities) earlier. A TIPS ladder is probably the best alternative to a COLA income annuity.

The U.S. government backs TIPS, while annuities are issued by insurance companies, often with state guarantees up to a specific limit.

Also, with TIPS, your money remains yours and can be passed on to heirs, whereas, in most cases, the insurer retains annuity premiums. Some annuities offer options to return a minimum capital or provide for a surviving spouse at an added cost.

Regarding longevity risk, a TIPS bond ladder portfolio could last 30 to 35 years with annual withdrawals of 4% to 4.5%, depending on inflation. In contrast, annuities continue payouts for life, with payout amounts determined by interest rates and actuarial longevity estimates.

Based on our ages (71 and 72), the payouts of both annuities at inception (7.8% for the nominal and 5.8% for the COLA) exceed TIPS payouts significantly due to the higher risk associated with insurance companies (mainly solvency risk) and our ages, and current long-term interest rates.

(Age is a significant factor as income annuity payouts increase with age due to reduced life expectancy. This is called the “mortality premium.”)

I’ve always thought that around age 70 would be the “sweet spot” for purchasing a lifetime annuity, and here I am.

What to do?

All three strategies have inflation risk. Here’s what I have concluded from my analysis so far:

1— Long periods of high inflation can decimate the purchasing power of a nominal SPIA. Because the payouts stay fixed for the annuity’s lifetime, they are particularly vulnerable to inflation. If I think inflation will be higher than average, the COLA annuity option may be a better choice.

2—The annual increases of the 3% COLA annuity aren’t tied to inflation, but they will offset some inflation—all of it if inflation is 3% or less. However, that benefit also comes at the cost of a lower initial payment, though there may be a point where the COLA annuity payout matches the income from the nominal SPIA. The COLA annuity also depreciates in purchasing power during prolonged periods of higher-than-average inflation.

3—The benefit of both annuities is that they will pay out for a lifetime. Of course, that means I select a lifetime and survivor payment option since I’m married and want my wife to continue to receive income if I’m gone. That certainly can’t be said for the SWR portfolio under certain circumstances.

4—The biggest concern with the SWR portfolio is survivability if withdrawals have to keep up with inflation, especially if inflation runs higher than average. However, using the “safe withdrawal rule” with average to slightly above-average inflation results in relatively high portfolio survival rates.

5—The most significant risk to the SWR portfolio is high inflation and longevity. As we discussed earlier, the SWR portfolio could be nearly depleted under high inflation conditions in about 20 years, and many retirees need it to last 25 or 30 years or more. It does much better with average inflation.

6—A TIPS ladder may be preferable to a COLA annuity if the annuity payout amount is less on a percentage basis. However, significant differences between the two may sway you one way or another.

These raise the question of what risks we are most willing to take—inflation, returns, or longevity. I can’t answer that question for you, and I am having difficulty answering it for my wife and me.

Should I purchase an annuity to provide guaranteed income for life, even if its purchasing power is reduced due to inflation, or continue to use an SWR portfolio when inflation and return risk are unknowable?

None of these strategies is a true inflation hedge. The 3% COLA annuity, which resembles an inflation-adjusted annuity but isn’t linked to the CPI, may be a wiser decision. However, as we’ve seen, it can lose purchasing power if inflation runs historically higher than the COLA rate chosen at purchase.

Then, there’s the significantly lower initial payout amount for the COLA annuity—it could take many years before the cumulative payments received are the same as those for each annuity contract.

The apparent trade-off is whether to accept a lower initial income and have it grow over time or annuitize fewer assets to receive the same initial income amount that does not otherwise grow.

Or, if I increased the initial contract amount for the COLA by about a third to $133,000, the initial payout would be roughly equal to the nominal SPIA with a contract for $100,000.

So here I am again

I’m now back where I started, with no perfect solution to provide all the guaranteed, lifetime, inflation-adjusted retirement my wife and I will need. Thankfully, we receive Social Security benefits that have traditionally been adjusted to account for inflation and can supply some of it.

With the best option (a CPI-U inflation-adjusted annuity with no annual cap) off the table, I have few options.

The thought still nags me that with interest rates so high right now, and my wife and I in our early 70s, I may miss a golden opportunity to snag a good deal on an income annuity, so I certainly haven’t ruled it out just yet.

But I’m still not ready to pull the trigger either—not because of emotion, but because I’ve done the best analysis I can. If inflation runs hot for the next decade or two, I see big problems with income annuities. Nobody knows whether that will happen.

I haven’t considered other annuity products. One that is becoming popular is the “multi-year guaranteed annuities” (MYGA; not to be confused with MAGA). But based on what I know about them, they’re more about taking advantage of rising interest rates than inflation, as they work like an insurance company version of a CD (or CD ladder).

Then, there are the other most popular annuity products: variable annuities, fixed index annuities, and deferred annuities. Could one of these be the ‘silver bullet’ I’m looking for?

Probably not.

I wouldn’t purchase a variable annuity or recommend one to anyone else. Fixed index annuities may be attractive in some ways but less so for those already in the distribution phase of retirement. A deferred annuity can sometimes make sense but does not cover current expenses.

What next?

This analysis has helped us understand the damaging long-term effects of inflation on specific strategies in isolation from each other. However, I haven’t analyzed the performance of a hybrid approach that combines an SWR portfolio of stocks and bonds with an income annuity in a large enough allocation to provide the income needed and Social Security to cover our essential living expenses.

This is an interesting scenario because many financial professionals and academics have suggested that such a strategy is the most effective and efficient way to provide lifetime income with the minimum level of risk necessary.

That will be the topic of my next article. This time, I’ll use my own circumstances to do the analysis—with inflation “baked in”—to answer the question, “Would I be better off with an annuity as part of my retirement portfolio?”.