Updated December 2025 to reflect the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA)

I’ve written previously about withdrawing from my Traditional IRA to help fund our retirement. I’ve also described how I began making Qualified Charitable Distributions (QCDs) in early 2023 after turning 70½

In a recent article, I explained how I might optimize my income tax withholding schedule while fully complying with IRS rules. My most recent article explained when and how much my RMDs will be in 2025. So, in this article, I’ll bring it all together and explain how I came up with a withdrawal plan for RMDs for spending and taxes, and QCDs for giving.

Important Update: Since this article was originally published in January 2025, Congress passed and President Trump signed the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA) on July 4, 2025. This legislation includes several provisions that significantly impact retirement planning and tax strategy for seniors, which I'll address throughout this updated article.

First, I need to fully understand the income tax implications, regardless of when I send in withholding for them. Then, I want to calculate the minimal monthly withdrawal that I would have to make to satisfy the IRS’ RMD requirement, assuming I also make additional withdrawals and use them to:

- Make quarterly QCDs for charitable contributions that partially satisfy the RMD requirement; and,

- Make a lump-sum withdrawal in December 2025 to send to the IRS for income tax withholding, which will also count toward my RMD.

Understanding the tax implications of RMDs

If you read anything about RMDs and taxes, you’ll probably see the phrase “tax torpedo.” That sounds pretty foreboding, right? Torpedo—boom!

I don’t know if anyone knows exactly where the phrase “tax torpedo” came from. But it makes sense; it refers to how a significant increase in your taxable income due to withdrawing RMDs from your taxable retirement accounts can “torpedo” your marginal tax rate.

Still, “torpedo” sounds a little hyperbolic to me, but we’ll see.

Perhaps you’re a couple filing jointly, receiving Social Security benefits, and withdrawing from your IRA to fund your retirement, and your “provisional income” is over $32,000. In that case, an ever-increasing portion of your Social Security benefit is subject to income taxes.

For higher incomes, up to 85% of your Social Security benefit is subject to income taxes, which can significantly impact your net after-tax benefit.

The tax torpedo happens when your Social Security benefits, which may not be fully taxable on their own, become more taxable because of other income sources. This creates a domino effect in which each additional dollar of income increases your taxable income by more than $1.

Confused? Well, let’s look at an example couple who are over 65 and file jointly but are not yet at RMD age, with the following income sources:

- $25,000 from a pension

- $10,000 from IRA withdrawals

- $1,000 in interest and dividends

- $50,000 in Social Security benefits

The IRS calculates your provisional income to determine how much of your Social Security benefits are taxable. Provisional income includes:

- All taxable income (like pensions, IRA withdrawals, and interest)

- Tax-free income (like municipal bond interest)

- Half of your Social Security benefits

Our couple’s provisional income is:

$25,000 (Pension) + $10,000 (IRA) + $1,000 (Interest) + 50% × $50,000 (Social Security) = $61,500

Because their provisional income exceeds $44,000 (the threshold for couples), up to 85% of their Social Security benefits become taxable. You may already be in that category (I am).

So what does this have to do with RMDs, you ask?

Suppose our example couple reaches RMD age and has to increase their IRA withdrawals by $10,000. That extra withdrawal increases their provisional income to $71,500. As a result, an additional $8,500 of their Social Security benefits becomes taxable.

So, even though they withdrew only $10,000, their taxable income increased by $18,500! This means they pay taxes on the withdrawal and extra taxable Social Security benefits.

Their effective tax rate on the $10,000 withdrawal isn’t the expected 12%—it’s more like 22.2%. This is the “tax torpedo” in action.

If the withdrawal was unplanned (RMDs shouldn’t be), then the “torpedo tax” may come as a surprise. But for most, this is more of a “phenomenon” than something they should lose sleep over. Still, understanding what’s happening here is good, as it isn’t insignificant.

As discussed in the last article, the tax torpedo could also push your MAGI above an IRMAA threshold, raising your Medicare premiums and creating a “double whammy.” This would amplify the torpedo effect.

This may be unavoidable for some, but probably because they have large IRA account balances or lots of extra retirement income, neither of which is bad in itself.

How the OBBBA affects the “tax torpedo”

The OBBBA introduces a new deduction for seniors that can help mitigate the tax torpedo effect. For tax years 2025 through 2028, individuals age 65 and older can claim an additional deduction of up to $6,000 ($12,000 for married couples filing jointly where both spouses are 65 or older).

The new senior deduction is available whether you itemize or take the standard deduction. It reduces your Adjusted Gross Income (AGI), which can help reduce the tax on Social Security benefits (which is why the claim that there is “no tax on Social Security” isn’t entirely accurate).

This deduction isn’t available to all taxpayers. It phases out for Modified AGI (MAGI) above $75,000 for single filers and $150,000 for married filing jointly. The deduction is reduced by 6% for each dollar of MAGI above these thresholds and completely phases out at $175,000 for singles and $250,000 for married filing jointly.

Perhaps most importantly for planning purposes, it’s a temporary provision that expires after the 2028 tax year

This deduction is particularly powerful for RMD planning because it directly reduces your AGI. A lower AGI means less of your Social Security benefits may be subject to taxation, which can significantly soften the tax torpedo effect.

For example, if our couple above qualifies for the full $12,000 deduction, their taxable income would be reduced by that amount, potentially moving some of their Social Security benefits back into the non-taxable range.

Paying taxes with RMDs

QCDs are made using RMDs, which is why they can be used to make charitable contributions and satisfy some (or all) of your RMD requirements, whether you itemize or not.

You may not realize you can also pay your quarterly tax estimates (withholding) using RMDs. All you have to do is take a distribution from your taxable IRA and elect withholding at a percentage, up to 100%.

For example, if your RMD is $10,000 and you anticipate your total tax bill will be approximately that amount, you could ask your IRA custodian to withhold 100% of taxes before the end of the tax year. That equates to paying $2,500 spread out over four quarterly payments.

Mine is a more likely scenario. I plan to use a percentage of my RMD withdrawals to pay my tax withholding, but I will do that as a lump sum at year-end to satisfy the IRS withholding rule. That will effectively reduce my RMD withdrawals each month.

QCDs and the new senior deduction

With the introduction of the OBBBA senior deduction, QCDs become even more strategically important. Here’s why:

QCDs are excluded entirely from your AGI. This is crucial because the new $6,000 senior deduction phases out based on your MAGI. By using QCDs to satisfy some or all of your RMD requirement, you keep your AGI lower, which helps you maximize or preserve eligibility for the new senior deduction.

The senior deduction may also reduce the tax on Social Security benefits, as a lower percentage of your benefits may be taxable. It may also help high-income retirees avoid or minimize IRMAA Medicare premium surcharges by keeping them in more favorable tax brackets.

The 2025 QCD limit is $108,000, which provides significant flexibility for charitable giving while managing your tax situation.

What if you don’t need the money?

If you don’t need to spend your RMDs in retirement, consider yourself fortunate, as that probably means you have adequate income from other sources. Fortunately, you can always reinvest them in a taxable brokerage account (after the government gets its share).

Those fortunate few who don’t need their RMDs to live on may prefer not to take annual distributions, especially if it might push them into a higher marginal bracket or cause them to lose the new senior deduction.

For those folks (I am not one of them), it’s good to remember that you have to withdraw the money (and pay the taxes), but you don’t have to spend it. You can invest it in a taxable brokerage account if you wish.

IRAs, RMDs, QCDs, and the IRS, oh my!

This section will be a bit technical, but please bear with me; you’ll understand why this is important (at least to me) by the end. The math isn’t complicated, and this is where I’ll bring it all together.

I need to do some additional math to calculate my optimal monthly withdrawal amount, which will differ from what I did in 2024 due to the new OBBBA provisions now in effect.

Of course, my “optimal rate”—the minimum amount I have to withdraw to satisfy my RMD—could be less than my “actual rate” because we decided to spend more. However, if we give more (via QCDs), our optimal rate would not change unless we can live on less. (If we give more in QCDs and withdraw more for spending, we will exceed the RMD, which is allowable.)

To illustrate, I’ll walk through the methodology with an example that mirrors our situation (and may be similar to yours now or in the future) but without using my actual account and income numbers.

First, I need to estimate taxable income for the year based on RMDs and Social Security (which could be less than what we actually spend) while also accounting for QCDs (which reduce RMDs), the new senior deduction (which reduces taxable income), and the Standard Deduction, which further reduces taxable income.

I can do that with some relatively simple calculations that I can symbolically express as follows:

TI = (IRA × RMDp) + (SS − SSnt) – QCD – SeniorDed – SD

Where:

- TI is Taxable Income

- IRA is the Individual Retirement Account EOY 2024 balance (I used $800,000 in this example)

- RMDp is the Required Minimum Distribution percentage (calculated from the IRS table I used in the previous article)

- SS is our total combined Social Security income

- SSnt is Non-Taxable SS income (a little complicated; see a calculator HERE)

- QCD is Qualified Charitable Distributions

- SeniorDed is the new senior deduction under OBBBA (up to $6,000 per individual, subject to phase-out)

- SD is the Standard Deduction (for married filing jointly, over 65, per the IRS)

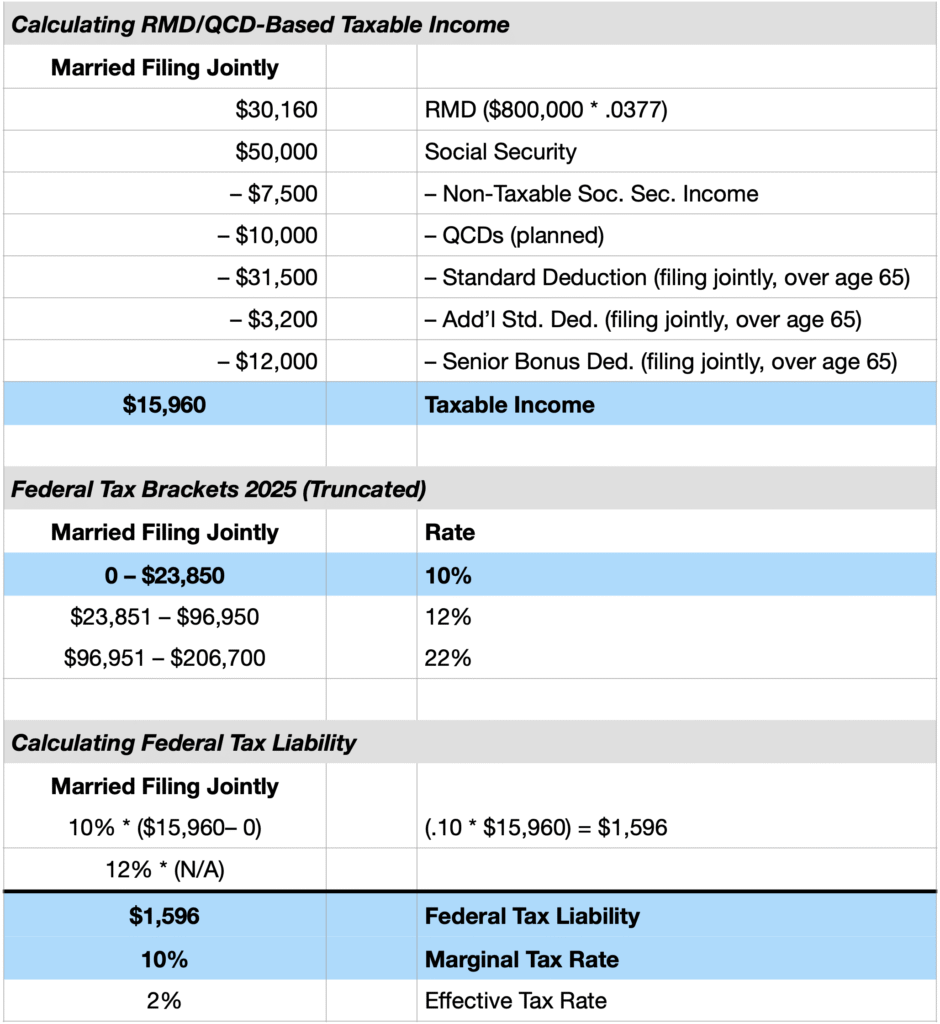

Example calculation with OBBBA senior deduction

Let’s work through an example, assuming:

- IRA balance: $800,000

- RMD percentage: 3.77% (age 75)

- Social Security: $50,000

- Non-taxable SS: $7,500

- QCD planned: $10,000

- Senior deduction: $12,000 (both spouses 65+, income below phase-out threshold)

- Standard deduction for 2025: $31,500 (married filing jointly)

- Additional standard deduction for seniors: $3,200 ($1,600 × 2)

As you can see, the calculations yield an estimated federal tax of approximately $1,600 (using the 2025 tax tables).

If I used my actual numbers in these calculations, I can determine the following:

- The minimum RMD I need to withdraw each month in 2025 to satisfy IRS requirements; and,

- The amount of income tax I need to withhold by the end of 2025 to satisfy IRS requirements.

The required RMD to be withdrawn each month (RMDm) can be calculated as follows:

RMDm = (RMD – QCD – ITe) ÷ 12

Using our example: RMDm = ($30,160 – $10,000 – $1,600) ÷ 12 = $1,547

Now I know the minimum amount I would have to withdraw each month, which, along with QCDs (made quarterly) and taxes (to be withheld in December 2025, as per my previous article), would fully satisfy the RMD of 3.77% at this income level, is $1,547.

You or I may want to spend more, which means we’d need to withdraw more from our IRA (or give less away).

If the former is assumed, there would be tax implications, but the RMD has already been satisfied, considering the QCDs and tax withholding are also withdrawn over the year. Giving away more QCDs would further reduce taxable income but would not affect the RMD.

Giving away more with QCDs would further reduce taxable income but would not affect the RMD.

My experience and 2025 planning

I used this exact method to calculate my RMDm for 2025 and started it at the beginning of the year. Since the OBBBA was signed in July 2025, I’ve had to recalibrate my strategy for the remainder of the year and through 2028.

I worked out the numbers using an updated spreadsheet that includes the senior deduction, and the results are pretty favorable. The key insight is that the senior deduction and QCDs work synergistically—both reduce taxable income, but QCDs also reduce AGI, which helps preserve the senior deduction.

I plan to withdraw monthly RMDs, make quarterly QCDs, and then withdraw a year-end RMD in addition to my regular December RMD, allocating 100% to federal tax withholding to satisfy IRS requirements. (As far as I know, my state doesn’t have a withholding requirement, but I need to research that.)

I will also do a mid-year checkpoint because, as I have said many times, expenses (and, therefore, withdrawals and taxes) can be unpredictable. Plus, I want to ensure I stay on track with my RMDs, though I am likely to exceed them. I’ll give you an update this time next year. (Here’s the year-end update: Getting My Year-End Tax Withholding Right: It’s Less Complicated Than It Sounds.)

Looking ahead: planning for 2026-2028 and beyond

Although I wrote in an article about taxes and the OBBBA that it’s tough for the government to institute a large tax cut like the senior bonus deduction for retirees and then take it away, the fact remains that the OBBBA senior deduction is temporary (expiring after 2028), so it’s worth considering a multi-year strategy in case a future Congress and administration eliminate it.

For 2025-2028, we want to maximize the benefit of the senior deduction by staying below the phase-out thresholds (QCDs can be VERY helpful with that if you have a higher income and are taking RMDs). You may delay Roth conversions that would push your MAGI above the thresholds. And consider accelerating income if it won’t trigger phase-outs.

For 2029 and beyond, we may need to be prepared for increased tax liability when the senior deduction expires. If you think that’s likely and have been doing Roth conversions, you may want to accelerate them during the 2025-2028 window. Building up taxable account balances during low-tax years can also be a good strategy. And as always, increasing QCDs in future years will help maintain a lower taxable income.

The OBBBA also made the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act tax rates permanent, which provides more certainty for long-term planning. The combination of lower tax rates and the temporary senior deduction creates a favorable four-year window (2025-2028) for retirement income planning.

Conclusion

The OBBBA has introduced significant changes to retirement tax planning, with the new senior deduction being the most impactful for retirees with moderate to upper-middle incomes. By understanding how this deduction interacts with RMDs, QCDs, and Social Security taxation, you can develop a more tax-efficient retirement income strategy.

The key takeaways:

- The $6,000 senior deduction (per person) provides meaningful tax relief through 2028

- QCDs become even more valuable as they reduce AGI and help preserve the senior deduction

- Strategic planning can help manage the phase-out and maximize benefits if you are vulnerable to them

- The temporary nature of the deduction requires multi-year planning

As always, everyone’s situation is unique, and these strategies should be adapted to your specific circumstances. Consider working with a tax professional or financial advisor to optimize your retirement income strategy in light of these new provisions.