This article is part of the Biblically-Informed Framework for Retirement Stewardship (BIFRS). (In fact, it describes the origin of it.)

When most people think about retirement planning, they picture calculators, spreadsheets, and savings goals. But for Christians, retirement is more than a financial target—it’s a new and hopeful life season calling for wisdom, faith, humility, and intentional stewardship.

So, what if we asked, “Do I have enough saved?”(This is a legitimate question, by the way.) And “Am I approaching retirement in a way that honors God?” Retirement isn’t an either/or proposition—it’s both/and.

Those are the questions behind this article, which was inspired by one I read based on a podcast interview with John Piper in which he was asked this by a listener named Linda:

Can you share any wisdom for thinking about how much money I should put away for retirement? I’m trying to balance being responsible in providing for my future while walking in faith and giving generously towards a mission beyond my tithe. I’m a natural saver but also have a tendency towards hoarding money that can be easily provoked when I read that I need to have $1.5 million dollars saved or invested before I can retire. I’ll never reach that level. What would you say to an American in my situation, about seven years from retirement age?

The interviewer (and author) further explained the $1.5 million number:

That question was in the air this spring after the Wall Street Journal featured a piece by Andrew Biggs (of the American Enterprise Institute) titled “You Don’t Need to Be a Millionaire to Retire” (April 18, 2024). In part, he wrote, “according to a new survey from Northwestern Mutual, the average American thinks he’ll need $1.5 million in savings to be financially secure in old age. If that were true, it’d be bad news. As USA Today recently reported, the average U.S. adult has saved only $88,400 for retirement. . . . Among those with between $50,000 to $99,999 in savings — a small fraction of what retirees are told they need — 3% found it hard to get by, 11% were just getting by, and 86% were either doing okay or living comfortably.” A big disparity here in the numbers.

My response

I guess Linda was more than a little uncomfortable with such a large number, which is understandable. However, neither Piper nor anyone else can answer Linda’s question with 100% accuracy.

$1.5 million is a sizeable amount that, based on the 4% “safe” withdrawal rate rule, might generate an annual income of $60,000 for 25 years. Does she need that much? Who can say? It could be much more than what she’ll need, depending on her other income sources in retirement. Or it could be too little, depending on her lifestyle, spending, health, and multiple other—and largely unknown and unpredictable— factors such as inflation, healthcare costs, long-term care needs, longevity, interest rates, and market performance.

That said, $88,400—the U.S. average quoted above—may be far too little for many retirees unless they have other significant income sources. For most, that will be Social Security. Will that plus $5,000 or $10,000 a year from savings be enough?

The reality is that no single number can tell her (or anyone else) how much she’ll need to save for retirement. There is no single dollar figure, no single multiple of final salary, and no single replacement percentage rate of preretirement earnings. In other words, no “magic number” can be generalized for everyone.

Some, such as the “Retirement Account Multiple” (RAM), which I use in my book Redeeming Retirement: A Practical Guide to Catch Up, can be used as a guideline but do not provide absolute certainty. Still, I like it because it’s specific to a person’s situation (current age, income, and savings) and based on reasonable assumptions.

The real challenge here is that Linda’s question is the wrong one to begin with, and the financial media is largely to blame for causing people to think that way about their retirement savings. It’s much better to start with your estimated living expenses and some reasonable predictions about the variables I listed above and work backward to calculate how much savings you might need to cover your essential spending after including other income sources like Social Security.

Finally, like Piper, I believe there is much more to retirement than running the numbers; more on that later so we can hear from him first.

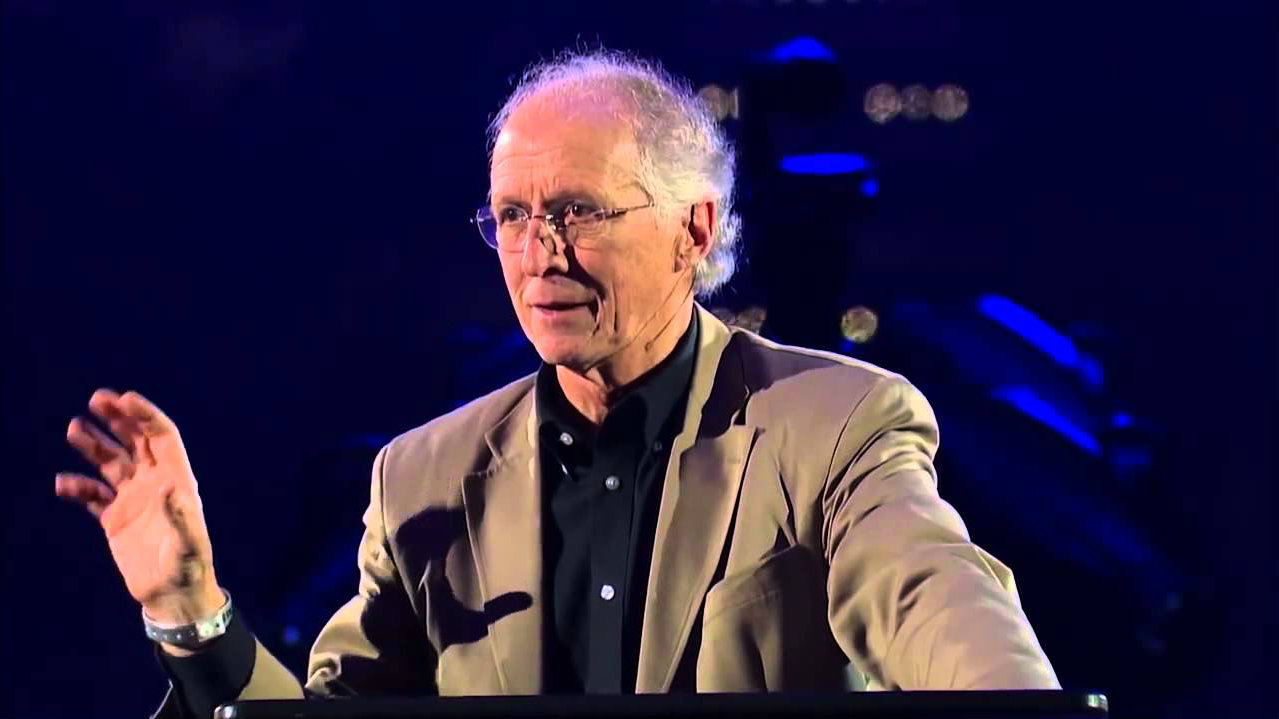

Piper’s response

Piper has written extensively about his views of retirement—online and in his books—so his thoughts are well-known. But he seldom talks about the financial aspects, which is what Linda’s question is about.

John Piper has spoken about “throttling” our lifestyle concerning money and retirement. He suggests that instead of accumulating wealth for comfort in retirement, Christians should consider how to use their resources to serve others and advance God’s kingdom. He encourages a lifestyle that prioritizes generosity and purpose over just focusing on financial security. So, Piper’s initial response was as I would have expected:

I think the first thing I would say is that I’m not a trained financial planner, and I am sure there are aspects of finance that I don’t know about and don’t understand, and that, therefore, to give any specific counsel, especially at a distance, would be foolhardy.

Not surprisingly, he didn’t get into specific numbers since we all know Piper isn’t a Certified Financial Planner (haha), which he acknowledged in the interview. However, equally unsurprisingly, Piper reflected on the question differently and responded with his insights from biblical teaching and practical stewardship to offer his perspective on a biblically informed retirement plan.

Piper’s biblical counsel focuses on three guiding principles: the Self-Sustaining Principle, the Caregiving Principle, and the Ministry Principle. Each one challenges cultural assumptions and reorients our thinking toward a God-honoring vision of life’s later years.

These principles, which I will discuss and add my thoughts to in this article, resonate with the themes I have espoused about retirement stewardship from the beginning.

1—The Self-Sustaining Principle

Live quietly, work diligently, and plan wisely.

In a podcast interview, John Piper offers this foundational insight:

The principle is that, insofar as we are able, we should earn our own living, pay our own way. And I think that applies from the day we start earning to the day we die.

His conviction on this is drawn from several passages in Paul’s letters to the Thessalonians:

You yourselves know how you ought to imitate us, because we were not idle when we were with you, nor did we eat anyone’s bread without paying for it, but with toil and labor we worked night and day, that we might not be a burden to any of you. (2 Thess. 3:7–8, ESV)

Now such persons we command and encourage in the Lord Jesus Christ to do their work quietly and to earn their own living. (2 Thess. 3:12, ESV)

Aspire to live quietly, and to mind your own affairs, and to work with your hands… so that you may walk properly before outsiders and be dependent on no one.” (1 Thess. 4:11–12, ESV)

Piper concludes that this principle should shape our view of retirement:

We should plan for how we will obey this principle in the last quarter of our lives—namely, to be financially self-supporting.

That doesn’t mean every believer must hit a certain financial number or retire with total financial independence. Instead, it suggests we plan wisely today so we won’t unnecessarily burden others tomorrow. Saving, investing, and preparing for future needs is not a lack of faith—it expresses wise biblical stewardship and personal responsibility.

My perspective

When thinking about retirement, there are some essential financial plans and decisions that we need to make. If you can no longer work, or should you choose to work for little or no pay, you will need to know how much money (i.e., “retirement assets”) you will need to have set aside to meet your essential living expenses—to ”sustain yourself.”

Those plans, decisions, and actions will mainly focus on ensuring that you will have enough and that it will last for the remainder of your (and/or your spouse’s) life. This can be a challenge, and many will need the help of a professional advisor.

Those plans require us to make important and sometimes difficult decisions. Several vital questions must be answered, mainly regarding your retirement assets, how you save and invest them, and your lifestyle and spending before and during retirement.

These include things like: How much should I save? How and where should I save? What kind of investments should I consider? Do I need to hire an advisor? What will inflation be like in the years ahead? How much will my investments return? Where will I live? How healthy will I be? How long will I live? And perhaps most importantly, how long will my money last?

Many of these questions can’t be answered, at least not with any precision. But retirement planning is not about perfection—it’s about making wise decisions in an uncertain world. Perhaps we should imagine looking back at the end of life and asking, “If things didn’t go as planned, would I still believe, by God’s grace, I made the best decisions I could, given what I knew and what God provided?”

That’s probably a helpful way to evaluate any significant financial decision—especially one as unpredictable as retirement. A good retirement plan, viewed retrospectively, would likely achieve your reasonable retirement goals.

In other words, a good plan is realistic, flexible, and aligned with your goals and values. It’s not just about reaching a certain number—like the often-quoted $1.5 million in savings—but about whether your plan can sustain your lifestyle, support your mission, and reflect your trust in God’s provision.

2—The Caregiving Principle

We care for others—and may one day need their care.

Of course, no one is guaranteed lifelong health or independence. The Bible also teaches that the family and church step in when self-sustainability is no longer possible.

Piper acknowledges this reality:

Millions of people will outlive their ability to be independent. And so the New Testament has another principle—namely, the caregiving obligations of family and church.

He draws from 1 Timothy, where Paul writes:

If anyone does not provide for his relatives, and especially for members of his household, he has denied the faith and is worse than an unbeliever.” (1 Tim. 5:8, ESV)

If any believing woman has relatives who are widows, let her care for them. Let the church not be burdened, so that it may care for those who are truly widows.” (1 Tim. 5:16, ESV)

Piper sees this as establishing an order of responsibility, and I would agree with him:

- First, family members care for one another.

- Then, the local church supports those with no family.

- Lastly, social safety nets like Social Security play a role in broader society.

He writes:

I suspect that the existence of legally mandatory Social Security in the wider society is owing to deeply rooted Christian influence that says we won’t throw away our old people but find a way to care for them.

This principle reminds us that retirement planning doesn’t stop with financial projections. It must include honest conversations about long-term needs and roles with family members, church leaders, and perhaps professional caregivers. It also calls Christians to be prepared not only to receive care but to offer it to aging parents, widowed relatives, and fellow church members.

My perspective

On the one hand, preparing for retirement with a good plan to fund it is one way we can try not to be a burden on others. We should, I believe, do all we can to avoid being a financial burden to our family and others.

Any reasonable retirement plan should leverage the government’s resources while minimizing our dependency on them to the greatest extent possible.

Some may choose to continue to work for pay in retirement or will have saved enough to meet their expenses, such that they can choose to work for little or no pay. We will hopefully reduce (but not necessarily eliminate) our dependence on the government, relying mainly on Social Security to help meet our expenses.

If Social Security is available, we must make wise decisions concerning when we start receiving benefits to maximize the lifetime income you (and/or your spouse) will receive.

However, if, as Piper suggests, we may need to rely on help from family or others, we will do all we can to minimize the amount and duration of the help we need. Even then, we may be at their mercy, so to speak. That’s when your family, brothers, and sisters in Christ are called to step up and serve.

We have been discussing “care” for the elderly, especially single women and widows, in our church. We have many folks over 60, but we are still in the minority. (I love being a part of a multi-demographic church.) This has caused me to realize how important it is for both natural and church families to care for their seniors well.

3—The Ministry Principle

Retirement isn’t about withdrawal from the mainstream of church life—it’s about new opportunities to serve and minister to others.

Perhaps the most significant part of Piper’s perspective is his view of retirement not as leisure but as a mission. He pushes back against the cultural assumption that retirement is primarily a time to relax, play, and check off a bucket list:

The Bible has no conception of what Americans typically think of as retirement—that is, working for forty or fifty years and then playing for fifteen or twenty years: fishing, golfing, shuffleboard, pickleball, yard work, travel, hobbies, bucket lists, as if heaven was supposed to begin at 65 rather than at death.

Instead, he calls believers to stay on mission to the very end:

As long as you are able, you lean toward meeting needs. That’s what you do. That’s what Christians do. They lean toward needs, not comfort.

This principle transforms how we plan our finances, use our time, and think about our purpose and calling in life. Retirement should not signal the end of giving, serving, or bearing fruit. Piper encourages retirees to continue giving to missions—even on a reduced income—and to find joy in active participation in ministry, not just supporters of it.

You don’t just give to missions—you become missions. You don’t think mainly of play; you think mainly of ministry.

Psalm 92:14 echoes this calling:

They still bear fruit in old age; they are ever full of sap and green.

Whether mentoring younger believers, volunteering at church, caring for grandchildren, or being present and prayerful, a biblically informed retirement includes purposeful service. Heaven is coming, but until then, there’s still work to do.

My perspective

As stewards of our time, talents, and financial assets, we won’t buy into the popular societal views of “retirement” as purely a time to cease the daily routine of work. We won’t view your later years as mainly consisting of a leisure lifestyle to which you are “entitled” after many years of work.

Sure, we are free to enjoy recreation and leisure as a gift from God, but we should also continue to use the skills and talents he has given us in productive ways. Some may begin a new career; others might start a new business, volunteer, or serve others in other ways but not for pay or a combination.

Many people, including Christians, enter retirement without a clear direction. They’ve checked off all the financial boxes to answer the question, “Can I retire?” but may not have answered the equally important one: “What will I do after I retire?”

Generosity also factors in; we use our surplus to bless others. If we are fortunate to have a surplus of what we need to live and for occasional enjoyment, we can rejoice by sharing it so that our abundance may bless others.

What would a biblically grounded retirement plan look like?

If I were to sum things up, this would be my modified framework for a biblically informed retirement plan, considering Piper’s contribution in that interview.

Putting it all together, here’s what I believe a biblically informed retirement plan looks like:

It starts with stewardship. Stewardship begins with recognizing that all we have belongs to God, and we are called to manage it faithfully—not only for our benefit but also for the good of others and the glory of God. It’s not limited to financial giving but encompasses every area of life, including how we approach work, retirement, and the decisions we make throughout all seasons of life.

It purposefully enjoys God’s good gifts: Retirement can include enjoying God’s good gifts like rest, travel, and hobbies, but these should not become our ultimate goals. Instead, retirement is an opportunity to pursue purpose beyond ourselves—living meaningfully and faithfully, in alignment with God’s calling, even as we enjoy a slower pace of life.

It prepares for self-sustainability: Save and invest faithfully, not to hoard, but to avoid being a burden and to enable continued service and generosity.

It includes a caregiving plan: Consider your family and church in your planning—how you might care for others now and how they might care for you later.

It makes room for ministry: Don’t retire from your calling or purpose. Whether mentoring, volunteering, giving, or simply being present for your family and church, you plan to stay active in service as long as God provides strength.

It is prudent but faith-filled: Make wise decisions based on what’s likely—not just what’s ideal—and trust God for what you can’t control. Avoid unnecessary risks, but you also avoid the trap of fear-driven hoarding.

It is flexible and changing. Circumstances and goals may change, markets shift, and your health may decline. A good plan adjusts over time and is revisited regularly.

It is heavenly-minded. As a Christian, strive to live knowing that your ultimate destination is not a dignity-filled retirement in this life but an eternal home in heaven. This knowledge will guide your critical decisions about living out your later years—how you spend your money, time, and talents.

As Piper says so well:

You stay zealous for good deeds right to the end. You magnify Jesus by serving. Heaven is coming. It’s not meant to drag forward. It’s meant to sustain hope and ministry.

Let that vision shape your retirement—not just the plan, but the purpose and behind it.