A family friend recently asked me to look at her retirement investment portfolio. It’s advisor-managed and has an allocation one-third S&P 500-indexed annuity, one-third stock and bond ETFs, and one-third cash (government money market).

Our friend is a recent retiree with a long planning horizon, so at first glance, I wondered why her portfolio had such a large cash allocation, especially considering the significant indexed-annuity and ETF bond fund allocations. Why not put more in stocks or fixed income (bonds, TIPS, or CDS)?

After a recent meeting, her advisor wrote the following in an email to her to explain the strategy:

“We are keeping a part of the IRA in Money Market paying 4.97% as of now, at no fee! You can see that we updated that together on our schedule B in the attachment, listing the Individual account and Money Market as 0 fee. Just holding it for you.”

I really like that he isn’t charging an AUM fee for assets held in the MMA (which, by the way, is 1.5% in this case—pretty high by any standard, in my opinion). Kudos to him for not charging a fee, but I take that back for what I think is too high a fee (1.5%).

(Note: I’m not opposed to a fiduciary advisor charging a fee for their services. All professionals deserve to be paid. But based on the level of complexity and size of her account, I think our friend’s fee should be in the .50% to 1.0% range and no higher.)

But I wondered what he is holding a third of the portfolio in cash for. To time the market (buy additional stock and/or bond funds when the time is right)? Or will all that cash stay in a money market account indefinitely?

I got more insight into the reason after talking with our friend.

Sadly, she told me she had been defrauded by a precious metals IRA investment (the huge up-front commission that she didn’t anticipate) and wanted to be as conservative as possible with the money she fortunately finally got back from it. I get that; it’s an understandable reaction after that experience.

In other words, she had been burned and was skittish about doing anything more aggressive with that money.

All retirees must decide what to do with their savings until they spend it. You could put it all in a savings account, under your mattress, or in a coffee can in your backyard. (I hear that even mattresses and coffee cans are paying competitive returns on cash lately, but I can’t verify that.)

A large cash allocation right now is somewhat understandable for some other good reasons: 1) It’s safer than stocks, 2) cash is paying higher interest than long-term bonds and CDs, and 3) the performance of bond funds has been disappointing over the last couple of years.

So why not put it in “cash” and keep it there? And to take things a little further, why not move all our fixed-income investments to cash and take advantage of its relative safety and high interest payments?

As Coach Courso would say, “Not so fast my friend!”

Most retirees can’t just “cash out” their stock and bond portfolio once they reach their retirement savings goal and call it a day the day they retire. There’s much more work—for you, your advisor if you have one, and your money—to do.

Why? Some studies have shown that if you put all your retirement savings in money market accounts, you have a pretty low chance of your money lasting 30 years or more with a 4% annual spending rate adjusted annually for inflation. It’s really just simple math.

Therefore, that’s probably not the best idea for most retirees unless they have millions saved. You may have successfully navigated the accumulation phase (congrats), but the spending (decumulation) phase is more challenging in many ways. You need to find a way for that portfolio to last for the rest of your life.

It’s possible you can do that with a market-based portfolio of stocks and bonds or by purchasing a lifetime income annuity. But for most of us, achieving with cash alone will be nearly impossible. Even if the money earns high interest, you’ll have the problem of inflation to deal with. Not to mention that interest rates change; they don’t stay high forever.

Although “cashing out” your portfolio when you retire is probably a poor strategy, reducing your portfolio’s risk is not. That might mean reducing your stock allocation to around 40% to 50% and putting the rest in bonds, cash, and perhaps a lifetime annuity.

My main point is that your investing challenges don’t end the day you retire. They become more difficult because of all the risks that must be accounted for. Not only do you no longer have income from work, but you’re spending down your portfolio, and you don’t know for exactly how long or what inflation will be. And if you decide to take less risk with your investments, it more often than not means lower returns.

You’ll need more help solving that problem than you’ll get from cash. Fortunately, although our friend is a little ‘spooked,’ she didn’t go to all cash; only a third of her assets are in cash. But as a conservative long-term investor in retirement, does it even make sense to have that much invested in cash? And what will she and her advisor do when interest rates eventually start to fall?

Bonds versus cash

Short-term interest rates have been rising since 2022 when the Fed started raising the Fed funds rate to combat inflation. As you can see in the chart below from bankrate.com, high-interest savings accounts sometimes pay more than 5%. Here are some examples from bankrate.com:

I typically hold between 5 and 10 percent of my retirement savings in ”cash” in a government cash reserves fund at Fidelity (FDRXX). It has a current yield of about 5.0%. I do this as part of my modified “bucket strategy.” (Mine is not an actual bucket strategy; it’s more of an income strategy and method.)

The majority of my portfolio is invested in fixed-income funds, including a sizable allocation to a Total Bond fund that’s yielding almost 5%, but its YTD total return is about 3.5%.

That same bond fund had a terrible year in 2022 (when the Fed started raising interest rates), losing almost 13%. It bounced back a little in 2023, gaining a little over 7%, and, as noted above, it has a net positive return so far this year.

Remember, the value of bonds falls when interest rates rise because higher rates make newer bonds more attractive to investors.

So, with intermediate and long-term bonds paying less interest than short-term treasuries and money market accounts, is it prudent to keep many of your fixed-income investments in cash or perhaps even move from bond funds to cash?

The answer to this question depends on what you want to achieve. If you have money invested that you will need in the next year or two, holding it in a high-interest-paying cash-like account makes a lot of sense.

On the other hand, if you’re near or in retirement and investing for the long haul, you might want to hold off. Bonds can be an important diversifier; they can prevent a total washout when the stock market craters.

Equally important, bonds have also performed better historically than the cash category, which includes money-market funds.

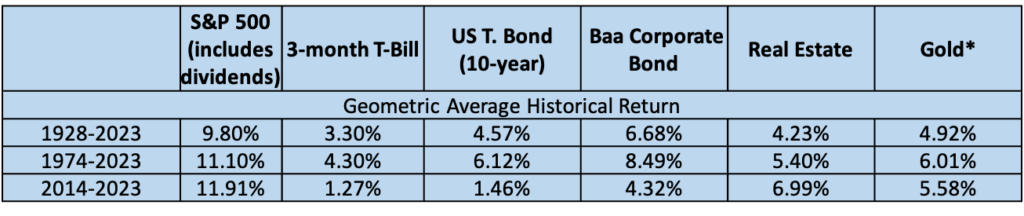

As you can see from the chart, from 1928 through 2023, 10-year US Treasury Bonds returned 4.57% compared with 3.3% for 3-month T-bills (comparable to cash), according to research by New York University finance professor Aswath Damodaran. The lowest-credit-quality investment-grade corporate bond earned twice as much but with much greater credit risk than US Treasuries.

It’s also worth noting that S&P 500 stock market returns overshadowed them both, with a 9.8% annual return but with much greater volatility, of course.

Perhaps you’re wondering, ”If this is true, then why is cash paying higher interest than intermediate and long-term bonds?”

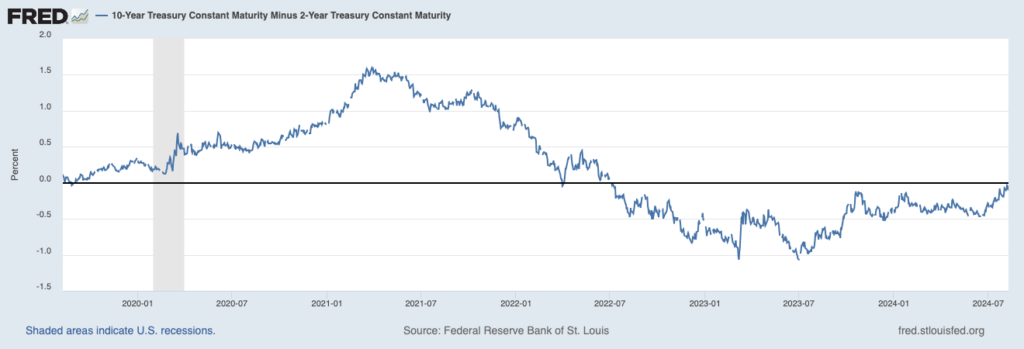

The short explanation is that we’ve been experiencing an economic phenomenon called an “inverted yield curve.” This is when short-term rates are higher than long-term rates, as the chart below from the St. Louis Fed illustrates:

This started in the Summer of 2022, and at one point in July 2023, 2-year T-Bills were paying 1.08% more interest than a 10-year Treasury Bond. However, as you can see, the gap is closing, and they are currently paying nearly the same.

This phenomenon usually signals that investors expect lower interest rates in the near future, possibly due to an impending recession when the Federal Reserve may reduce rates to stimulate the economy. (The Fed has signaled that it may start reducing rates as soon as next month.)

This takes us to the other side of the bond total return equation and why bonds can be good long-term investments: increased bond prices due to falling interest rates.

Bond prices have an inverse relationship with interest rates. When interest rates fall, bond prices rise. Holding a bond or bond fund long enough will eventually enable it to return to its par value. This is illustrated by this simple diagram from honestmath.com:

The amount by which a bond’s value increases and decreases is all about the math. It’s based on a formula that considers current interest rates, the number of interest payments until a bond matures, the amount of those payments, and the bond’s future face value.

This is why, if you liquidate intermediate and/or long-term bonds in favor of cash, the cost to buy back in in the future may be higher if interest rates fall. This could happen when inflation cools, and the Fed wants to stave off a recession. Investors increase demand for bonds or bond funds to lock in long-term yields to protect their income stream and drive up demand.

These market returns can give bonds a long-term advantage over cash in terms of total return. It’s also possible that a bond fund will pay higher yields when the yield curve normalizes (i.e., no longer “inverted”).

Your options

Suppose most of your fixed income is in cash or cash-like investments, and you expect interest rates to decrease. You may want to put some of your money in longer-duration bonds to benefit from potential price appreciation.

You might also consider investing (a little) in high-yield bonds. High-yield (aka “junk”) bonds might become more attractive with lower rates due to higher returns. However, be careful—these come with lower credit quality and, therefore, more default risk.

If most of your fixed-income assets are in short-term bond funds (nominal or inflation-protected), you might want to invest some in intermediate-term bonds with higher yields. (I’d avoid long-term bonds, but that’s just my opinion.)

Even if you keep some of your savings in cash, allocating a portion of your portfolio to bonds may be a good idea. Generally, investors far from retirement should own more stocks and fewer bonds because, over time, stocks are more likely to deliver the gains they’ll need (see the historical returns chart above).

Investors closer to retirement should own more bonds, partly because bonds can provide a stream of retirement income and provide some diversification away from stock market volatility.

One formula for determining the right balance of stocks and bonds is “120% minus your age.” If you are 40 years old, for example, you should hold 80% of your portfolio in stocks and 20% in bonds.

Still, as I have written before, I think it’s wise for those near or in retirement to keep some of their retirement in cash. One to three years’ worth of what you’d need to supplement other income sources to cover your essential living expenses seems about right.

If you’ll need your money within the next six months or a year, you should look at money-market funds, short-term CDs, or similar alternatives. And remember that there’s more to consider than just yields for each.

As always, it’s essential to consider your overall risk tolerance, time horizon, and spending needs when making investment decisions. Consulting with a fiduciary financial advisor can also yield personalized guidance tailored to your needs and keep you from making big mistakes.