This is the third and final article in a three-part series about the most important financial decisions that affect retirement stewardship.

Our saving and investing decisions, especially early on, dramatically affect what we will have when we retire. In fact, when you save (timing) may actually be more important than how much you save (amount) or what you do with your savings (investing).

A slack hand causes poverty, but the hand of the diligent makes rich. He who gathers in summer is a prudent son, but he who sleeps in harvest is a son who brings shame. (Proverbs 10:4-5 ESV)

There is some agrarian language in this proverb, and its wisdom applies in different contexts, but the essence of it is that when you are in the summer of your life (the early years), that’s the time to make hay (save); but if you slumber at harvest time (procrastinate or fail to save altogether), you could be in for a long, difficult winter (during your later season of life – i.e., “retirement”).

Saving decision – start early!

Perhaps you remember our little case study from a previous article about Susan, Dave, and Chris. Each made different decisions when they were in their 20s about saving for retirement:

- Susan – who invested $5,000/Year from 25 to 35, and then stopped for a total of $50,000 total invested

- Bill – who got started a little late, because he didn’t read this blog, and invested 5,000/Year from 35 to 65 , for a total of $150,000 total invested , and

- Chris – who was committed to living below his means and invested $5,000/Year from 25 to 65 , for total of $200,000 total invested

Look at the chart below. As the article’s author, Ray Mulligan, pointed out, it was Chris who started early and kept at it who had the most money available in their account at age 65, assuming the same rate of return over the entire time period (7% for this example) – more specifically, he would end up with over a million dollars!

You probably assumed that Bill came in second (he invested $200,000 whereas Susan only invested $50,000). But you’d be wrong. It was Susan who will have $562,683 while Bill will have a slightly smaller balance of $505,365!

How can that be, when Bill put in three times the amount as Susan? Well, it is because Susan’s money had a running head start and started growing 10 years earlier than Bill’s. So instead of having to take money out of her income every year, she allowed her money to make money for her.

The decision to save early takes the most advantage of the “power of compounding”. The “power” is in the fact that your money is earning money, and the money you earn on your money is earning money, etc. (it’s called a “geometric progression”), so it really grows over time.

Most people think investments are fun and glamorous. They think if they could just get large, “market-beating” returns from their investments, they would have it made; they would not have to work so hard or save so much.

But ironically, financial wealth is in a sense a by-product for those who do not seek it. It comes through working hard, spending less than you make, regularly saving, and then conservatively investing your surplus for reasonable returns such that they do not lose the capital you have accumulated, especially in the very critical years leading up to retirement.

If you’re older and got a late start saving for retirement, check out this series of articles.

Investing decision – grow your savings!

Okay, you’ve decided to save, now what? Well, you need to come up with an investment strategy to grow your savings based on several other important decisions:

Investing decision #1 – hire an adviser or do it yourself?

Your first major decision has to do with who is going to manage your investment assets. Do you want to manage them yourself or hire someone to do it for you?

If you are saving in a 401k/403b retirement account, you may already be a do-it-yourself (DIY) investor. Your company gives you a set of investment options in the form of fund choices and education materials to help you decide which ones make the most sense for you based on your age, risk tolerance, and investment goals. They may also give you investment classes or free counsel.

But ultimately, the choice is up to you, and, it’s up to you to monitor performance and decide when changes need to be made as you go.

If you are investing in an IRA, you will have to make the same decisions; you will just have many more options. There are many excellent financial services firms where you can set up a self-directed IRA account, and those institutions are usually, though not always, a reliable source of financial advice.

If you decide to be a do-it-yourself investor, I give you some tips in the Investing decision #3 – what to invest in section, below.

Most firms that you could use to hold your assets also offer a portfolio management service. The fee is typically a percentage of the assets under management, usually in the 0.2% to 1% range. Other firms may charge higher fees, or may also charge sales fees (commissions), which further add to your costs. (Keep in mind that these fees are in addition to any fees charged by your investments themselves.)

Which way should you go? Well, as I have noted elsewhere, I am a big fan of DIY investing, mainly for two reasons: 1) lower costs; and, 2) nobody cares about your investments as much as you do. But to do it, you need to educate yourself – you can read blogs, articles, and books, and even enroll in classes. Some people will choose to go that route. But I realize that most people don’t want to commit a significant amount of time and energy to learning about investing, much less actually doing it. So most will want to find a competent adviser they can trust to do it for them, which is a wise decision in most cases.

You can find a fee-only adviser in your area at napfa.org, letsmakeaplan.org or plannersearch.org. Then you might want to put together a list of questions. Some suggestions are the financial adviser interview questionnaire at garrettplanningnetwork.com and “Questions to Ask in Your Search” at plannersearch.org. Email the advisers on your list and ask them to send back a signed copy of their answers.

You can also Google each adviser’s name and that of his or her firm looking for lawsuits and customer disputes. Enter them on BrokerCheck, a website run by investment regulators; while not perfect, it should surface most instances of misbehavior.

Read the Form ADV brochure, a mandatory disclosure for many advisers, at adviserinfo.sec.gov. Pay special attention to fees and compensation. Some advisers claiming they are “fee-only” may in fact accept commissions that could induce them to put their interests ahead of yours. If an adviser charges annual fees, look for 1% or less.

I also strongly suggest you find one that adheres to the “fiduciary standard” to ensure that they put your interests ahead of their own. Personal recommendations are very valuable. Talk with several potential advisers before you make up your mind. Also make sure you know what your costs are; they can really impact your earnings over the long term.

Investing decision #2 – where to invest?

The next decision is where to put your money. Whether you are a DIY’er or not, you will have to rely on a financial institution to be a custodian of your assets and execute your investing decisions. Of course, you could put your money in a box in a safe, or under your mattress, but neither is recommended. This is a very important decision because where you invest will determine your costs, your level of service, and also what kind of information and advice you will have access to.

You essentially have a couple of ways to go: Use a financial services firm or go with an individual, independent adviser.

There are lots of financial firms out there – banks, brokerages, insurance companies, etc. – so you have lots of choices. Unquestionably, most have good management and customer service, but, in my opinion, there are a few that stand out from the rest due to their unique client-owned business models that tend to ensure that customers come first:

Vanguard is the nation’s largest and fastest-growing mutual fund company. It is known for its wide diversity of low-cost index funds and ETFs, as well as its relatively low cost actively managed mutual funds. I don’t have my IRA account with Vanguard, but I do own some of their funds. Vanguard is client-owned, so there is no conflict of interest between clients and owners.

USAA is set up as an “insurance exchange” under state law. Customers or “members” as they are called, again, are like owners. Profits are retained or returned to members. I am a member, and I receive a “dividend” check each year as earnings that are returned to members. USAA requires you to have some military connection in your family to join (my father was a career Marine), and prides itself on operating with “military values.” I’m most familiar with their insurance products and brokerage (where I have my self-directed IRA); their costs have been competitive or better, and their customer service superior, in my experience.

There are other companies, for-profit, that stand out to me and in the industry:

Charles Schwab is a discount brokerage with a reputation for good value and service. They are inexpensive, offer an excellent web site, and conservative, sensible analysis of the market. They offer a broad range of their own funds with no loads or transaction fees. (I own one of their stock funds.)

Fidelity is a discount brokerage with a similar profile to Schwab. Though they are a 60-year old company, they are privately owned, which means no shareholder pressure for short-term performance. They’ve been ranked #1 overall for best online brokers by Kiplinger several times. I had my IRA with Fidelity and invested in their funds for many years.

TIAA-CREF is a 100-year-old company that is becoming more widely known. It has a great reputation in the academic and non-profit community as a not-for-profit financial firm. They specialize in retirement funds and pensions, annuities, and various types of investments.

An alternative to using a large financial firm is to choose an independent individual investment adviser. Such individual advisers (or the firms they work for) are typically Registered Investment Advisers (RIA). These are usually fee-only, specializing in actively managed portfolios, so DIY is not an option. These firms typically choose the custodian of your assets for you and tend to use discount brokerages like Fidelity, Schwab, or TD Ameritrade.

To select an individual investment advisor, use the guidelines provided in investing decision #1, above.

Many Christians prefer working with a Christian adviser. That’s fine, but I think competence, experience, knowledge, and wisdom are equally important. They are your financial adviser, not your pastor.

Use caution adopting an individual insurance agent or stock broker as your adviser. Usually, these folks are in sales and highly motivated by commissions. (I’m not saying that these folks are bad, only that they may have different motivations than a fee-only adviser.)

Investing decision #3 – what to invest in?

This is about deciding what you’re going to invest in and why.

Some people’s strategy for investing is to “play the markets.” They buy and sell and try to time market ups and downs in order to make a profit. Although there is the occasional success story, this has been proven to be a losing strategy in the vast majority of cases.

Here’s the reality: the stock market is us – all of us – we are the market. So, it’s actually a little foolish for the average person to believe that they, or even a competent paid adviser, can “beat the market.” Mr. Market is the sum of all the feelings, sentiments, beliefs, and behaviors of everyone who invests in the market – many who are much more knowledgeable and experienced than you or I. So, apart from the nominal economic growth that we all benefit from, you’ve got to beat somebody else at the same game and by more than what it costs you to do so in order to come out ahead. And that someone could be a very knowledgeable and experienced Wall Street hedge fund manager running a multi-million dollar portfolio.

My point is that it really doesn’t make sense to go toe-to-toe with the professionals on Wall Street, especially when we’re talking about the money that you will need to live on in retirement. You’ll be much better off owning a cheaply-managed basket containing many different stocks – a “mutual fund.” I like index funds as they virtually ensure that, at a minimum, you’ll capture your portion of the economic growth of whatever sectors you’re investing in at a relatively low cost. If you want to pay a more for “well-run” mutual funds, be my guest, but keep in mind that less than 20 percent of them will actually do better than the indexes.

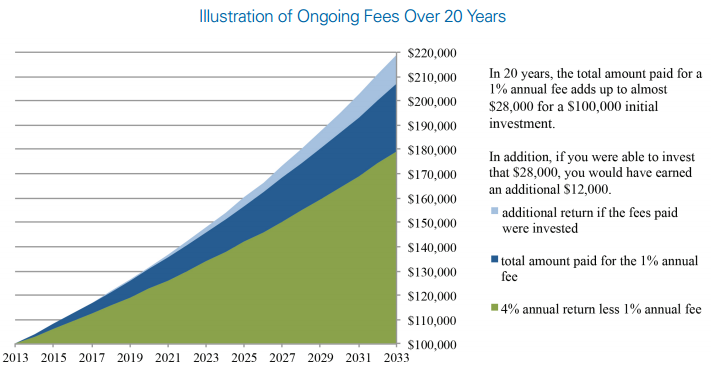

The chart below from an excellent publication by the SEC shows the effect of a 1% ongoing fee on a $100,000 investment portfolio that grows 4% annually over 20 years. As the portfolio grows, so do the fees, and that is money that is not available for investing. The total loss is $40,000 over 20 years!

The bottom line on fees is that they really do matter and can dramatically reduce returns, particularly over long time horizons as the impact of fees compound in reverse.

In addition to stock funds, and to deal with market volatility, you need to invest in more than just stocks. (Sorry, this is where I differ slightly with Dave Ramsey). What I’m talking about is diversification. Most experts suggest that you at a minimum add bonds to your portfolio as they are the traditional diversifier for stocks. Bonds tend to (but do not always) hold most of their value when stocks fall. This helps you to keep your sweaty little hands off your portfolio when the ride gets bumpy and also gives you some income when needed.

Now you’d be right to ask how much to hold in bonds. Well, here it comes – the standard answer in personal finance when there really isn’t an exact answer: it all depends on your “risk tolerance.” How exactly to gauge your risk tolerance can be difficult, unless you’ve experienced a major stock market tumble such as the two or three we’ve had in as many decades.

Actually, many experts say that it’s not too important whether your percentages are 60/40, 40/60, or 50/50 for your stock and bond allocations – it’s actually more important to starting saving early, keep your expenses low, don’t get greedy or fearful when the markets take their inevitable swings, don’t put all your eggs in one basket, and stick with your strategy.

I have personally been close to a pretty simple balanced 60/40 stock/bond asset allocation for most of my working and investing life and it’s worked out okay. Could I have made much more at certain times had I been more aggressive with stocks? Perhaps, and sometimes I wish I had. But I also would have lost a lot more when things went south, like in 2008. Regular saving and preservation of capital were more important to me than marginal gains.

I’m entering a different season of life now, so I’m much lighter in stocks, pretty heavy in cash, and I have added some alternative investments (3% Gold, 7% Real Estate, and 4% Preferred Stock funds) for further diversification. My fixed income investments are mostly in a single diversified bond fund, but I also hold an international bond fund and an inflation-protected fund.

At 14.7% cash, I wouldn’t necessarily carry that much into retirement as I would want to put more of it to work generating income. But I am “keeping my powder dry” for future buying opportunities as I think both stocks and bonds are too highly valued right now. Given the right opportunity, I would like to add to some of my stock funds. At retirement, my plan is to keep two years of living expenses in cash so that I can ride out any stock market storm without having to sell damaged assets.

My portfolio is only eleven funds total, excluding cash. Here’s a high-level breakdown:My goals are fairly simple: Maintain a diversified, relatively conservative and stable portfolio that is capable of generating both growth and income (with emphasis on income now that I am getting closer to retirement). As a DIY investor, greater stability helps me to resist the urge to sell dinged assets during a market downturn. I hope to have some growth in the future (although I don’t expect the stock market to do as well over the next 10 years as it has done in the last 10 years), but it’s more important for me to have some relatively safe, conservative investments that will survive a bad stock market, even a prolonged one if necessary.

If you decide to DIY, there are some ways to make it as simple and straightforward and easy as possible.

First, you could consider investing in a “Target Date Retirement Fund”. These are intended to be “one stop shop” funds-of-funds where the fund manager does all the work for you (asset allocation, fund selections, rebalancing, etc.). If you examine Vanguard’s target date funds, for example, you can identify the specific funds they use and also the allocation between stocks and bonds and then use that as a model. Or, you can just invest in a fund based on your planned retirement date. They are an excellent option, especially for smaller balance accounts or those looking for a “set it and forget it” option. In addition to Vanguard, Fidelity, Schwab, T. Rowe Price, and TIAA-CREF are all known for these types of funds.

Another option is to use a “model portfolio” approach. This is a basic portfolio construct that you can follow that may or may not include specific fund recommendations. An excellent example is Sound Mind Investing. (I have subscribed to their service for some time now.) They offer several different strategies and model portfolio options and fund recommendations that you can use to make your own decisions. (There is a fee for their service.) Other good examples are PaulMerriam.com (formerly fundadvice.com) and the “Boglehead” Lazy Portfolios (https://www.bogleheads.org/wiki/Lazy_portfolios), which lists a number of asset allocation plans most based on Vanguard funds that are easy to implement and maintain.

Technology has given you the opportunity to use a “Roboadviser”, either by investing with them (for a fee) or by looking into the asset allocation models of their automated investment services. Three of the most popular are Betterment, Wealthfront, and Future Advisers. Wealthfront, for example, has an excellent white paper on its investment philosophy. It not only shows its asset allocation plans for taxable and retirement accounts, but it also provides an in-depth explanation of the asset classes it has chosen.

Finally, there are many good books and blogs on investing that provide excellent ideas on asset allocation plans. I have listed several on the Resources page of this blog. If you’re a “beginner”, consider: Sound Mind Investing Handbook (by Austin Pryor), The Bogleheads Guide to Investing (by the Bogleheads), The Little Book of Common Sense Investing (by John C. Bogle), The Little Book of Bulletproof Investing (by Ben Stein & Phil DeMuth), and Investing Made Simple (by Mike Piper, CPA). To go more in-depth, look at Unconventional Success: A Fundamental Approach to Personal Investment (by David F. Swensen), A Wealth of Common Sense (by Ben Carlson), and Financial Fitness Forever (by Paul Merriman & Richard Buck).

Investing decision #4 – how often to adjust your portfolio?

Some people love to tinker with their investments. But that can be dangerous to your financial health. If you want a hobby, learn to fish. Most of the time it’s better to just be patient and let the financial markets work in your favor. If you try to outsmart or out-time them, you can get into trouble.

But what about rebalancing? Don’t you need to “adjust” your holdings periodically based on how they’ve been performing? I’m not sure how important it is, actually. You may gain a fraction of a percent in performance from rebalancing if you do it faithfully over many years. Unless your asset allocation gets way out of whack from your risk tolerance — say more than 10% for more than a year — rebalancing is optional, in my opinion. If you want to keep things precisely balanced all the time, you can accomplish that by simply holding balanced funds.

The most important thing

The most important thing I can recommend when it comes to investing is that you eschew complexity and embrace simplicity and low costs. In fact, RUN toward both. Excellent examples of the “majesty of simplicity” and low cost are the Retirement Target-Date Funds I mentioned above. You get broad diversification on the cheap, especially if you go to a low-cost provider such as Vanguard, Fidelity, or Schwab.

Diversification is a good thing. But scattering your money across multiple accounts and products is not. Except for a small 401K at my current employer, the bulk of my retirement investments are in eleven funds in a single IRA account. They are highly visible and transparent and very manageable. In my experience, the most complex financial products are the expensive ones – meaning high commissions and fees. Keep things simple and most importantly understandable. With retirement date or lifestyle target funds, you can hold your entire retirement savings in a single balanced mutual fund, if you are so inclined.

Also, remember this: there is no such thing as a perfect portfolio. There is no single best investment. You can only make good, well-informed choices that align with your values and goals and are therefore good enough. No matter what choice you make, there will always be somebody somewhere who has done better. So what? As long as you meet your goals, what else really matters?

Finally, you have to avoid the big mistakes – risky, expensive investments that you don’t understand, or buying and selling at the wrong times based on emotion. You only need to meet your personal investment objectives. Avoid comparisons and “if only” thinking. Do your homework and make a good-enough decision. Then patiently leave your money alone and get on with life. That’s what you save and invest for in the first place, and the essence of investing and wise retirement stewardship.