I recently came across the phrase “epochal change.” It was used to describe the domestic and global economic changes that I discussed in a recent article titled “A Challenging Time for Retirement Investors.”

The basic idea is that we have reached a historical inflection point due to dramatic economic and political changes.

Of course, we are also witnessing unprecedented social, cultural, and spiritual changes, most of which we would view unfavorably from a traditional Judeo-Christian perspective.

Thus, some more “prophetically-inclined” Christians believe this could be the beginning of the end, culminating in the visible return of Jesus to the earth.

I believe in the Second Coming, but I honestly have no idea whether it will be tomorrow, next week, next year, or many decades from now. So, I’m hesitant to make such a connection.

Plus, there have been economic “inflection points” before: the Industrial Revolution, the Great Depression, the post-WWII baby boom, and the 2008 real estate crash, to name a few.

There have also been cultural inflection points: the Declaration of Independence and then the Bill of Rights, the Emancipation Proclamation, the Women’s Suffrage Movement, the Civil Rights Movement, the Sexual Revolution of the 60s, the legalization of abortion, the LGBTQ Movement, and the BLM Movement.

I think it’s valid to use “epochal” to definitionally describe the changes that are likely to result in the next 10 or 20 years being very different from what we have known in the past, economically speaking, and also due to cultural and political trends.

But I don’t think the ”epochal change” we are currently experiencing is about impending disaster or Armageddon (though it could be). Yet, I do think it’s wise to “discern the times” as part of wise biblical stewardship (1 Kings 3:10-12, Prov. 1:5, Prov. 17:24, Matt. 16:3, Luke 12:53).

So, if the past is no longer the future, then it may be unwise to use the past as a guide to predict future outcomes. Instead, it may be helpful to understand what is going on and why, the likely long-term effects (which may be different from the past), and how to best respond as wise retirement stewards.

The trigger

Some economists would say that we didn’t reach this so-called inflection point suddenly—it’s been underway for decades, due primarily to historically low interest rates and the ever-increasing federal debt.

But the trigger for the current ”inflection point” was, in the opinion of many economists, the trillions of dollars of fiscal stimulus added to the already exponentially growing (and basically out of control) government debt in response to the coronavirus pandemic.

Some have said it was just a matter of time before things started to unravel, as over-leveraged and over-heated free-market economies often do.

Adding to all this is the changing geopolitical landscape.

The economic and militaristic dominance of the U.S. in the world, and in some ways, the influence on the spread and strength of democratic governments, has waned in recent decades. This seems to have opened the door to greater international instability. (That may be one of the reasons there is so much autocratic ”muscle flexing’ going on all over the globe.)

So, the high inflation and rising interest rates we see now, following the most elevated stock market valuations and bond prices in history, were predictable.

Inflation broke out in May 2021 due to the Fed’s easy money policies and pandemic-related supply chain issues. The war in Ukraine has further exacerbated the situation.

This has created instability in the financial markets. (Still, some are surprisingly calling for additional stimulus! That seems like throwing gas on a fire.)

I’ll leave it to the economists and politicians to determine whether pumping even more into an economy that is already awash in cash is a good idea. I think you can tell where I stand on that question.

The affects

The most damaging effect of all these things is inflation, which, predictably, quickly went out of control, faster and more strongly than the Fed apparently ever imagined it would. (I seem to remember the word “transitory” being bantered around.)

I get that the dynamics of such a large and complex economy as ours, which is increasingly tied to an even larger and more complex global economy, can be hard (and at times, impossible) to predict.

Still, I think it’s fair to say that Fed missed it on this one. They could have prevented it (at least to some extent) only if they had started taking decisive action several years ago.

Even as recently as the fall of 2021, the Fed said it wouldn’t raise interest rates (to combat inflation) until stable and sustainable employment numbers. By the end of 2021, it pointed to a .75% increase in 2022 but is now aiming at 2.5%, which has rattled the financial markets.

Adding to inflation’s damage are the global political tensions and instability we are currently experiencing. However, the world has always had these challenges, so the war alone would likely not have been the cause of a significant economic reset, rising oil prices notwithstanding.

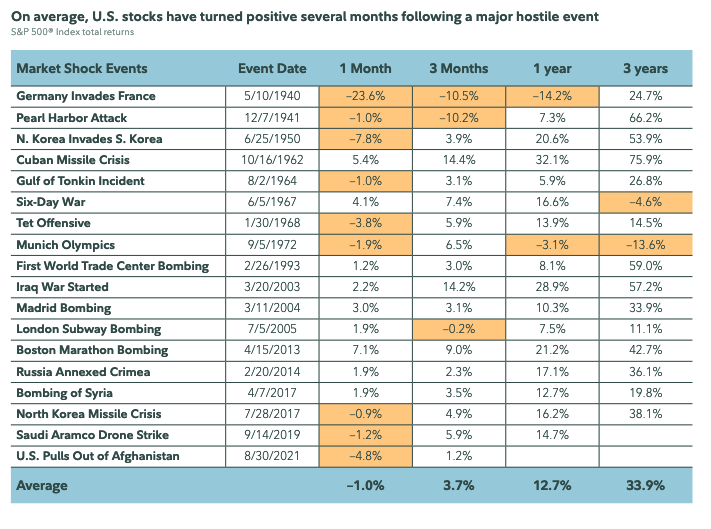

The war in Ukraine may resolve one way or another in months or a year or two. As this chart from Fidelity’s April 2022 Market Perspective shows and Fidelity pointed out, ”On average, U.S. stocks have turned positive several months following a major hostile event”:

But the war undoubtedly contributed to inflation, but it was already becoming a problem, as was the prospect of rising interest rates.

You may be surprised to learn that the Bible isn’t silent about inflation. It teaches that individuals (and governments) should have honest weights and measures. Deut. 25:13–16 says,

You shall not have in your bag two kinds of weights, a large and a small. You shall not have in your house two kinds of measures, a large and a small. A full and fair weight you shall have, a full and fair measure you shall have, that your days may be long in the land that the Lord your God is giving you. For all who do such things, all who act dishonestly, are an abomination to the Lord your God.

The problem with inflation is that it causes a dollar to no longer be worth a dollar. A dollar given for a dollar’s worth of goods or services, or for repayment of a dollar of debt is not full payment. (And lest we forget, inflation actually helps the federal government by reducing the real value of its debt.)

For example, at the average annual inflation of only 2.14%, today’s dollar would have bought $1.24 worth of goods just 20 years ago in 2012. A decade of 4% inflation instead of 2% would reduce purchasing power by 18% by the end of that period.

This violates the biblical principle of honest weights and measures as someone who honestly earns a dollar is no longer to purchase a dollar’s worth of goods.

Beyond the obvious impacts that inflation has on the purchasing power of everyday people (it causes them to reduce spending and borrowing, which affects the overall economy), out-of-control inflation has another consequence: the Fed has to change monetary policy to combat it.

That’s significant because they have to “tighten” monetary policy instead of easing it. (“Easing” stimulates economic growth, and “tightening” slows it. You can read more about this in a previous article.)

Whereas the last 40 years have been generally deflationary (meaning lower inflation), the current economic environment is historically high inflation (i.e., not seen in 40 years), forcing the Fed to act and act forcibly.

Rising inflation and interest rates are a “double whammy” (that’s not a technical financial term). They necessitate changes to conventional investment strategies because stocks and bonds both can both move to the downside together, thereby removing the diversification that risk management with a traditional “balanced” stocks and bonds portfolio provided.

In practical terms, this has already happened, and we have all felt it to one degree or another.

The traditional 60% stocks/40% bonds portfolio has been hit hard. Furthermore, the prospects for 8% to 10% returns for the balanced portfolio over the next ten years or so aren’t very good.

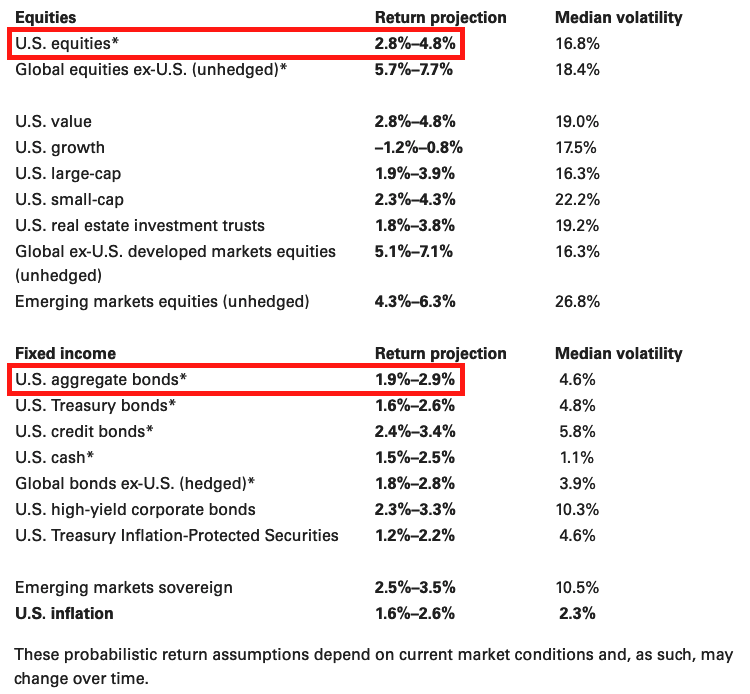

Look at Vanguard’s asset-class return 10-year outlooks for U.S. stocks and bonds from their April 2022 market perspective:

Note that stocks, which have averaged 9.6% annual growth since the Great Depression, are predicted to grow at only 3% to 5%. And bonds, which have averaged 5.6%, are estimated to return 1% to 3%.

According to Forbes, the average balanced 60% stocks/40% bonds portfolio has averaged 8.5%. Based on the Vanguard estimates, it may average only 3.2% annually over the next decade.

If inflation is on the high end (averaging 2.5%+), then real (after inflation) bond returns could be negative, and stocks would return approximately 2.5% or less in real terms. That’s nothing like the average returns we have seen over the last 20 years when stocks averaged over 10%, and inflation was around 2% (netting real returns of about 8%).

We are already in a time of negative interest rates (which means inflation is higher than short-term interest rates), which has significant investment and retirement planning implications.

For sure, inflation isn’t the only reason we’ve entered a period of dramatic change, and it may not be the most important one.

The bigger issue is the Fed and how far it seems to be behind the curve fighting inflation. That alone raises concern about how well it can manage the current inflation without taking the U.S. economy into a recession.

A rock and a hard place

The Fed is in a tough spot because they need to raise interest rates dramatically and reduce liquidity in the system to fight runaway inflation.

But they also have to be careful.

Two decades of historically low rates have created what many see as a debt bubble at every level of the economy—consumers, corporations, and the government—due to incentivized (and given the extremely low rates, understandable) borrowing.

This combination of high inflation and such large debt bubbles hasn’t existed before, and not to the extent, it does now.

So, if the Fed raises rates as high as necessary to combat inflation (which might mean much higher than the 2.5% it has announced), we could have a much larger solvency problem resulting in debt defaults that would negatively affect stocks, bonds, and real estate.

The reason is that the bubbles that were considered acceptable before would quickly become highly unacceptable. This might lead to a collapse in market values that could be permanent unless very low rates return and persist for a long time.

If you have been invested in stocks over the last twenty years (since the Great Recession of 2008–2009), you have seen results that averaged over 10% per year:

Stock returns have been both unusually high but also relatively stable as well. There were downturns here and there, but the markets amply rewarded you if you hung on and didn’t sell. In other words, it was a “rational” stock market bubble.

But whether we knew it or not, this performance was founded mainly on the idea that the lowest interest rates in history would continue indefinitely. And although we all knew that rates would probably rise sometime, we had a false sense of security because we believed (hoped?) that the Fed would control it so that there would be no catastrophic impact on the markets.

I remember a quote that I read many years ago: “With large corporations, as with oil tankers, bigness confers advantages. But the ability to turn around quickly is not one of them.”

I could rephrase that quote for this context: “With large, complex economies, bigness confers advantages. But the ability for the Fed to turn them in a different direction quickly is not one of them.”

Economists say that to reign in inflation the Fed must raise rates above their “neutral” level, which has traditionally been about 2–3%, to a level higher than the rise in underlying inflation. That suggests a federal-funds rate of 5–6% or higher, which we have not seen in almost 20 years.

As I noted earlier, according to basic monetary theory, it would probably tame rising inflation, but it would likely kick off a recession.

Also, according to one source, it typically takes at least 9 months for the economy to see the effects of the Fed’s actions. But that is based on the Fed taking action now for problems it sees nine months down the road.

That’s not the case this time around; the Fed is clearly way behind the 8-ball this time.

If inflation remains high but rising rates and ongoing supply chain issues reduce economic growth (recessionary trend), we could enter a period of “stagflation“—high inflation and slow economic growth. (This is similar to what happened in the 1970s due to a global oil shortage.)

Typically, in a “stagflationary” environment, both stocks and bonds don’t perform well. We had extended bear markets during the 1970s stagflation period.

Still, according to some, there are reasons for optimism due to accelerating advances in digitizing assets, decentralization, biotech, clean energy, and other innovative future economic growth opportunities, some of which may be big “game-changers.”

The U.S. economy has shown remarkable resilience (as per the earlier Fidelity chart), but due to the systemic nature of some of the current changes, this time may actually be different—only time will tell.

What to do?

Stable inflation averaging 2% and interest rates higher than zero might be tolerable to a healthy growing economy, but it’s tough to see how the Fed can get there. Drastic action will probably be needed, which all its undesirable effects.

This all leaves us with a challenging question: What to do?

It might be reasonable to expect this to result in what economists call “mean reversion,” which means a return to historical averages for inflation, interest rates, and stock returns.

That’s a reasonable assumption if we think the future will look like the past, but it may be a less likely outcome based on the factors we’ve discussed.

Could inflation and interest rates moderate and the stock market maintain 10% average annual returns in the future? It’s certainly possible, but not as likely as it used to be.

It’s more likely that overall returns will be less for stocks and bonds—perhaps significantly less—than in the last several decades. Therefore, it may be wise to reevaluate your underlying retirement planning assumptions, especially for moderate-to-conservative portfolios containing traditional assets.

Even then, as I have written many times before, only God knows the future. (And for him, the future isn’t really the future—he exists in the past, present, and future simultaneously.) As Ecc. 3:15 says,

That which is, already has been; that which is to be, already has been; and God seeks what has been driven away.

This does not mean that history literally repeats itself repeatedly (although it sometimes seems to). It is really a glimpse into eternity past and a reminder that God governs the world now as he always has from the beginning. He will continue to do so into eternity future when he returns everything to its originally intended state of perfection.

In other words, no matter what happens, God is in control. So, it’s best to base our stewardship decisions on uncertainties due to our human limitations while prayerfully making decisions that we believe to be consistent with God’s will.

Neither you nor I, or anyone else, really know what the financial markets will do from here (though I expect them to be volatile, no matter what). We can only try to discern the times and steward our resources well.

During times of economic upheaval, we may have to make lifestyle changes and adjustments to our spending. We can also look for other ways to invest.

(I will explore this further in a follow-up article, but history has shown that categories of investments tend to perform betting during inflationary times. I will also discuss some of the adjustments I have been making to my portfolio and retirement income strategy.)

There are things we can continue to do: save, spend wisely, and give generously, which are foundational to good stewardship no matter what happens in the financial markets.