This article is part of the Retirement Financial Life Equation (RFLE) series. It was initially published on January 4, 2023, and updated in February 2026.

An important preliminary note:

Given the significant losses sustained by both the stock and bond markets in 2022, I started 2023 with a series of articles about “safe” retirement income and the roles that bonds and other instruments may play in providing it. Now, nearly three years later, with the benefit of hindsight and dramatically changed market conditions, it’s time to revisit and update this foundational question.

But from the outset, I want to reiterate some important “first principles” when it comes to our finances and stewardship in retirement:

- Our hope and treasure, which is to say our hearts, can’t be in our retirement accounts, investments, or our “guaranteed income” from Social Security or other sources. Instead, it must be in God’s goodness and faithfulness to us as his children.

- Meeting our reasonable spending (and charitable giving) needs in retirement is a good and wise use of the resources God has entrusted to us. Seeking to minimize risk and provide for future income is commended in Scripture and is good for us, our families, our churches, and our community.

- I may occasionally use the phrase “guaranteed income,” but there really is no such thing. Nothing in this fallen world can truly be “guaranteed” except the things God has promised us. Even then, some of his promises are conditional based on our faithfulness and obedience to his Word.

- Through his common grace, God has given both Christians and non-Christians tools and resources to help manage their retirement income wisely and in alignment with biblical principles. Fixed-income securities, such as individual bonds and bond funds, are such tools when used appropriately in a diversified retirement portfolio.

When I wrote the original version of this article in January 2023, the bond market was reeling from its worst year in modern history. The Vanguard Total Bond Market Index Fund (VBTLX) had lost approximately 13% in 2022, unprecedented for what was supposed to be a “safe” investment. Many retirees, including myself, were questioning whether bonds deserved any place in our portfolios.

Fast forward to December 2025, and the picture has changed dramatically. The yield of total bond funds is over 4%, and 10-year Treasuries are yielding almost as much. Some investment-grade corporate bonds are paying almost 5%, and TIP real yields are nearly 2% plus inflation protection. Wow, what a difference a couple of years makes.

The bond market has not only recovered from 2022’s losses but has delivered solid returns in 2023-2024 and continues to offer attractive yields going into 2026. The cumulative recovery has restored value, and today’s yields offer compelling income opportunities for retirees.

Not long ago, I wrote about the sea change underway in the financial markets and underlying economic dynamics, primarily due to the Fed’s complete reversal of decades of “quantitative easing” (QE) with aggressive “quantitative tightening” (QT).

At that time, we had entered what appeared to be a new era of higher interest rates, higher inflation, and lower expectations for stock market returns. The transition was painful, particularly for bond investors.

The transition is now complete. We’re in more of a “normalized” interest rate environment that retirees haven’t seen in over 15 years. The Federal Reserve successfully engineered a “soft landing”—avoiding recession while bringing inflation down from its 9.1% peak in June 2022 to around 2.5-3.0% in 2025. This is close enough to the Fed’s 2% target to allow some modest rate cuts while maintaining policy flexibility.

Consequently, individual bonds and bond funds, which had an awful year in 2022, have since recovered and now offer yields that were unimaginable during the 2010-2021 period. Paired with stock market volatility, bonds have reasserted their role as portfolio diversifiers and income generators.

The Vanguard Total Bond Market Index Admiral Fund (VBTLX)—an intermediate-term fund—has recovered its 2022 losses and currently yields approximately 4.3%. This compares with yields below 2% for most of the 2010s.

Based on these developments, the question “do bonds still belong in a retiree’s portfolio?” has been decisively answered: Yes, they do—perhaps more so now than at any point in the past 15 years.

The concerns of 2022-2023 were valid at the time, but market conditions have evolved favorably:

- Bonds are once again providing meaningful income (4%-5% yields)

- The diversification benefit has been restored as bond-stock correlations normalized

- Interest rate volatility has moderated

- Starting yields near 4-5% suggest attractive forward returns

When I asked, “Aren’t bonds supposed to go up when stocks go down?” the answer remains “usually.” What happened in 2022 was unusual—both stocks and bonds fell together because the Fed was aggressively raising rates to combat inflation. This temporarily broke the normal negative correlation.

Now, in 2025, that correlation has largely been restored. When stocks experience volatility, bonds tend to hold their value or appreciate, providing the portfolio ballast they’re supposed to deliver.

The question “should I shift more of my portfolio to stocks?” depends on your individual circumstances, but the case for bonds has strengthened considerably:

- Higher yields mean better risk-adjusted returns

- Starting yields predict future returns (historical R-squared of 0.85)

- With bonds yielding 4-5%, the opportunity cost of holding them versus stocks has shrunk

- Retirees seeking income now have genuine options in bonds

Questions

When QT started, my retirement portfolio (at age 69, then) was about 40 percent stocks and 60 percent bonds and cash. After significant consideration and some rebalancing through my 70s, I’ve recently adjusted my allocation to approximately 30% stocks, 60% bonds, and 10% cash—slightly more conservative as I age, while still following my bucket strategy.

I continue to hold short- and intermediate-term bond funds, including a Treasury Inflation Protection Securities (TIPS) fund.

My bond funds were down an average of 9% in 2022—something I never expected at the time. However, those losses have been substantially recovered. More importantly, the elevated yields I’m now earning (4-5% range) provide significantly better income than the 1-2% I was receiving in 2020-2021.

This experience reinforces an important lesson: short-term losses, while painful, don’t invalidate bonds’ long-term role in a diversified portfolio. The question isn’t whether bonds will ever decline (they will), but whether they serve their purpose over time (they do).

This has caused me to ask myself these questions—and now, with three years of additional experience and a normalized rate environment, I can provide updated answers:

- Should I own bonds at all? If so, does a balanced portfolio still make sense?

- 2025 Answer: Absolutely yes. With yields at 4-5%, bonds are fulfilling both their income and diversification roles effectively.

- Should I own individual bonds or bond funds?

- 2025 Answer: For most retirees, bond funds remain the better choice due to diversification, professional management, and ease of use. However, bond ladders have become more attractive with normalized yields.

- Would I be better off with a “bond ladder”?

- 2025 Answer: Possibly, especially for known future expenses. Current yields make ladders viable again. This depends on your specific situation and need for flexibility.

- Should I buy more TIPS?

- 2025 Answer: TIPS deserve a place in most retiree portfolios with real yields around 2% + inflation protection—the best real yields since 2009.

- Should I buy individual TIPS (and build a TIPS ladder) or a TIPS fund?

- 2025 Answer: Both have merit. TIPS ladders now offer 4.5% inflation-adjusted withdrawal rates, according to Morningstar. TIPS funds provide simplicity and professional management.

- How would I build a TIPS bond ladder?

- This remains relevant, and I’ll address it in a future updated article.

I tackled the first question in this article when I originally wrote it, and the others in subsequent posts, which I’ll be updating. The key difference now is that the answers are much more favorable to bonds than they were in early 2023.

Alternatives to bonds

There are only a few basic investment alternatives for your retirement savings.

You can use some (or all) of it to buy an annuity. In combination with Social Security, you will receive ‘guaranteed’ payments from both for as long as you live. You’re good to go if that’s all you need to fund your retirement.

With current Single Premium Immediate Annuity (SPIA) rates at approximately 8.1% for a 73-year-old—the highest payouts in over a decade—annuities have become significantly more attractive than when I wrote this in 2023. This represents a dramatic improvement from the 5-6% rates available in 2020-2021.

With that strategy, you won’t run out of money; however, inflation could be a problem. A worst-case inflation scenario over 20 or 30 years could significantly reduce the real value of the annuity payments—and you won’t have anything left when you die. That may or may not be important to you.

For detailed analysis of annuities and when they make sense, see my complete annuities series and my personal analysis, where I discuss why I’ve been hesitant—though the dramatically improved rates are making me reconsider.

The next major alternative is to buy bonds. You can buy them individually or in a bond fund. Most people who do the former use individual bonds to build bond “ladders.” (A CD ladder offers similar benefits, and with CDs now paying 4-5% for 1-3 year maturities, they’ve become viable again after years in the wilderness.)

That’s why some experts say that bond ladders built with individual TIPS offer one of the safest routes (since they adjust for inflation). According to Morningstar’s 2025 research, a 30-year TIPS ladder can support an inflation-adjusted starting withdrawal rate of 4.5%—with 100% success and complete depletion at year 30. This is significantly better than what was available in the ultra-low rate environment of 2020-2021.

Ladders can be built using many different types of bonds:

- Treasury bonds: Currently yielding ~4.0-4.5% depending on maturity

- Investment-grade corporate bonds: 4.25-5.25% for 5-10 year maturities

- TIPS: ~2.0% real yield + inflation adjustments

- Municipal bonds: 3-4% (tax-free for those in high brackets)

Comparing these two options, we can see some differences.

First, with a bond ladder, assuming you spend all the money of each “rung” in the ladder the year it matures, you’ll run out of cash when you reach the last rung, perhaps 20 or 30 years. But the annuity (along with Social Security) will pay as long as you’re alive, which could be longer than 30 years.

In either case, you’re out of money when you die (with the ladder) or the annuity payments stop. Whether that matters to you is a personal decision based on your legacy goals.

The second difference is that when you buy an annuity, you give your money (principal) to an insurance company. In contrast, with a bond ladder, you keep the money in your brokerage account invested in bonds.

If you live less than 30 years, you may have something left over with a ladder. Plus, you can sell some bonds at any time should you need to raise cash, but you may sell at a loss if prices are down. With improved yields, individual bonds held to maturity now provide more predictable income than during the ultra-low rate era.

Investing in a stock portfolio is the third major option that gets the most attention. (Many retirees do this and prefer dividend-paying stocks.)

With a stock-based portfolio, if you need more than the dividends they pay, you will have to sell stock shares (hopefully, appreciated ones) to generate cash flow.

With stocks, if you don’t spend too much, and stocks do very well as an asset class over the 20 or 30 years of your retirement, you could end up with something to leave behind. Or, if stocks do poorly or you experience a significant sequence of returns risk, you could run out of money before you die.

So, stocks have lots of upside but just as much downside. That’s why we often combine them with bonds to create “balanced” portfolios.

I like dividend-paying stocks (funds) and using those dividends as income in retirement. Depending on how much I spend, I don’t have to sell stock fund shares very often. It fits well with my bucket strategy for funding my retirement.

The problem, of course, is that these stocks (funds) don’t always go up and sometimes go down—a lot. You probably remember 2000 (dot com bust), 2008 (real estate crash), 2020 (pandemic), and 2022 (inflation shock). The S&P 500 fell almost 20% in 2022 due to rising interest rates and inflation, though it has since recovered and reached new highs in 2024.

Although most retirees want (and perhaps need) to own some stocks for long-term growth and inflation protection, they should probably also hold some bonds. Many studies have shown that owning bonds can reduce a portfolio’s overall risk, even though returns may also be reduced.

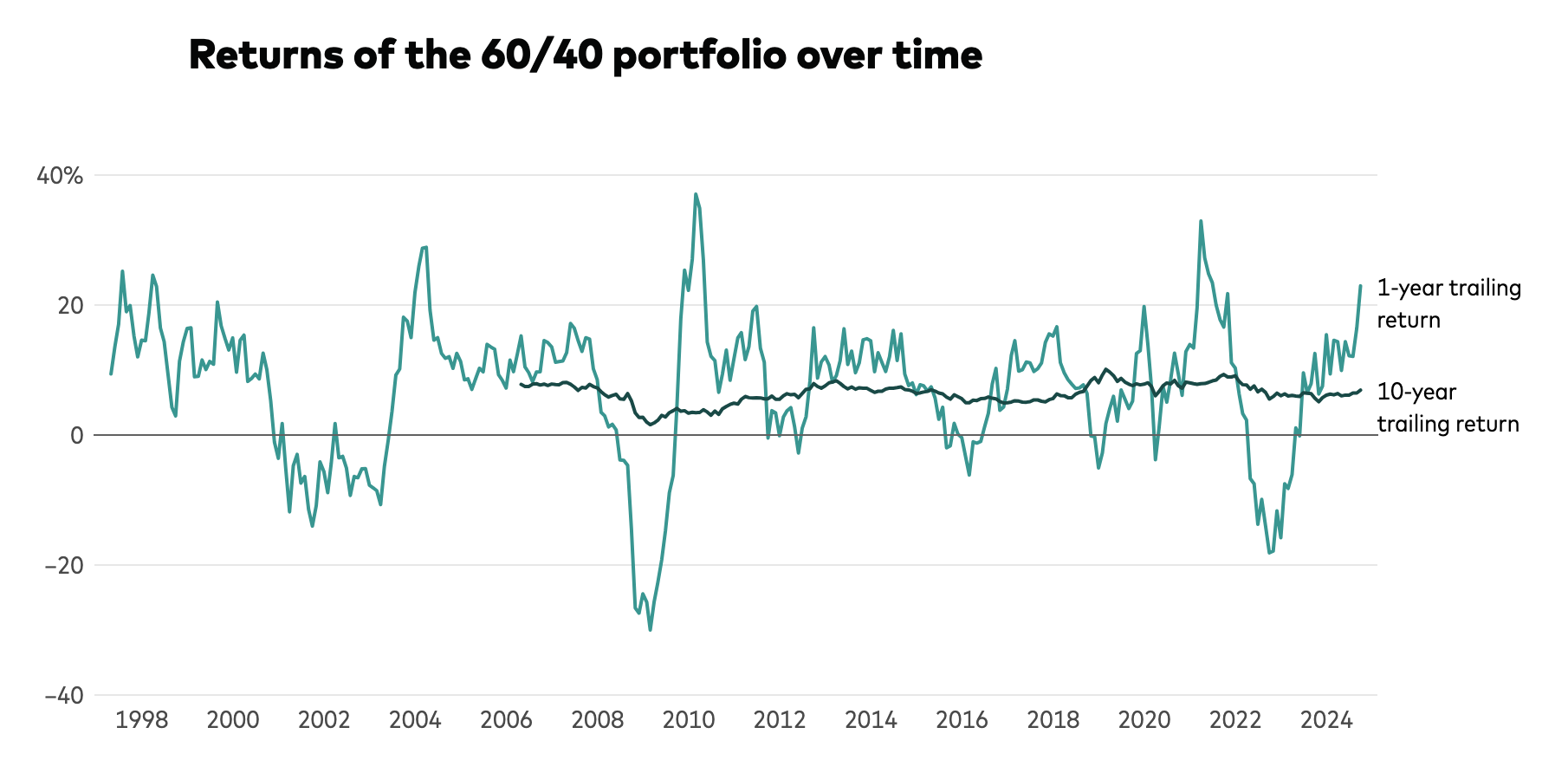

Of course, how much of your portfolio should be in bonds has always been debatable. A 60% stocks and 40% bonds portfolio (a.k.a. a “balanced” portfolio) has performed very well on a risk-adjusted basis since 2000, with an average trailing return of almost 7% as of September 2024:

As the Vanguard article noted, “. . . the 60/40 portfolio can be a wise choice for clients with a moderate risk tolerance seeking broad diversification and a track record of solid long-term results.” But remember that this was a time of dramatic interest rate reductions, which drove up bond prices. It also assumes you’ve stayed invested through all the ups and downs since then.

Recent research from Morningstar and Bill Bengen provides updated guidance:

- Morningstar (2025): For conservative fixed withdrawals (3.9% starting rate), optimal stock allocation is 20-50% over a 30-year horizon

- Bill Bengen (2025): Recommends 47-75% stocks for a 4.7% starting withdrawal rate, with a key warning: reducing stock allocation during retirement is the worst approach

- Traditional balanced (60/40 or 50/50): Still works well for most retirees seeking moderate risk/return

The key insight: There’s no one-size-fits-all allocation. Your ideal mix depends on:

- Your withdrawal rate and strategy (fixed vs. variable)

- Your time horizon and age

- Your other income sources (Social Security, pension)

- Your risk tolerance and need for sleep-at-night stability

- Your legacy goals

As I noted above, at age 73, I’ve settled on approximately 30% stocks, 60% bonds, and 10% cash—slightly more conservative than traditional balanced portfolios, but appropriate for my age, income needs, and circumstances.

Another good reason to own bonds (and why I have about 60 percent of my portfolio invested in them) is that they can provide a relatively safe, predictable income stream.

Individual bond and fund yields are significantly higher than they were in 2020-2021.

Good reasons to keep them

So should we buy (or hold) bonds in our portfolios? I think there are compelling reasons to do so—and these reasons are even stronger today than when I wrote this article in 2023:

Reason #1 – If you invest in stocks, bonds improve your risk/reward quotient.

This remains true, and perhaps more so now. With bonds yielding 4-5%, they’re contributing meaningful returns while still providing diversification. The correlation between stocks and bonds has returned to more normal patterns after the unusual 2022 period.

Reason #2 – They provide a relatively safe, predictable income.

This is significantly more compelling in 2025 than it was in 2020-2021. With yields at 4-5%, bonds can now genuinely serve as income generators without requiring excessive risk-taking. The “safety” factor—relative to interest rate risk—remains relevant, though with rates largely stabilized, interest rate risk has moderated from 2022’s extreme levels.

Individual bonds held to maturity eliminate concerns about price volatility. Bond funds still carry some interest rate risk, but with yields at current levels, even moderate price fluctuations are offset by income over reasonable holding periods.

Inflation risk remains real, which is why TIPS deserve consideration in most retiree portfolios.

Reason #3 – Matching bond funds’ durations to known spending needs provides structure.

While less precise than individual bond ladders, this approach remains valuable. With improved yields, bond funds at various duration points (short, intermediate, long-term) can be effectively matched to bucket strategy needs without the complexity of managing individual bonds. This is what I do in my own portfolio as part of my bucket strategy.

Reason #4 – Bond funds offer simplicity, low costs, and professional management.

Buying individual bonds can be expensive and complex, particularly for smaller investors. Bond funds (especially ETFs and index funds) provide:

- Instant diversification across hundreds of bonds

- Professional management

- Daily liquidity

- Transparent pricing

- Very low costs (often 0.03-0.10% expense ratios)

- Automatic reinvestment if desired

Reason #5 – Bond funds are professionally managed, transparent, and easy to understand.

This remains true. You can see exactly what bonds the fund holds, understand the duration and credit quality, and know the yield you’re receiving. The mechanics are straightforward, making them accessible to all investors.

Reason #6 (for 2025) – Starting yields strongly predict future returns.

Historical data shows an R-squared of 0.85 between bond starting yields and subsequent 5-year returns. With intermediate-term investment-grade bonds currently yielding 4-5%, investors can reasonably expect annualized returns in that range or slightly higher over the next five years—much better than the sub-2% returns available during the 2010s.

Reason #7 (2025) – The opportunity cost versus stocks has narrowed.

When bonds yielded 1-2%, the gap versus expected stock returns (6-8%) was enormous, making bonds less attractive. With bonds now yielding 4-5% and stock market valuations elevated (suggesting more modest forward returns), the risk-adjusted case for bonds has strengthened considerably.

You may not need bonds if you decide to go the annuity route. A fixed-income annuity is a lot like a bond issued by an insurance company (they usually invest the money you give them in bonds, by the way). An annuity works like a bond with a lifetime coupon with no value when you die.

But unless you annuitize all your retirement savings (which I wouldn’t recommend), you probably want to own some bonds to tamp down your stock portfolio volatility and provide income for living expenses in future years.

Recommendation

At age 73, I’m maintaining my current bond/cash allocation of about 70% (60% bonds, 10% cash). This is slightly more conservative than the often-recommended balanced 60/40 or 50/50 portfolios, but it’s appropriate for my age and income needs.

If you’re younger, say in your early 60s, you may want a more balanced 50/50 or 60/40 stocks/bonds portfolio. If you’re in your late 70s or 80s, moving to 70-80% bonds and cash makes sense to preserve capital and reduce volatility.

The key insight from 2022-2025: Don’t abandon bonds when they’re down. That’s often the worst time to sell. Instead, maintain your allocation through market cycles and rebalance when appropriate. Those who stuck with their bond allocations through 2022’s losses were rewarded with recovery and are now enjoying 4-5% yields that were unimaginable in the prior decade.

But the next questions we need to consider are whether to own individual bonds or bond funds, and whether it’s time to “lock in” some of these yields with individual bonds, perhaps using a bond ladder.

I’ll tackle those questions in the next article in this series.