Well, the (MY) day of ”reckoning” is here. No, not the final judgement; I’m talking about sending the IRS their due (i.e., tax withholding) for 2025 for taxes due in April, 2026.

As regular readers know, I’ve done more writing than usual about taxes, charitable giving, and the new tax laws. That’s because:

- There’s much ado about taxes in retirement, and I want to demystify the hype, hyperbole, and fear-mongering that pervade much of the financial media, and help you and me better understand the basics of the tax code and the lifetime benefits of “tax arbitrage.”

- I want to minimize the taxes we pay through that tax arbitrage as wise stewards, so we can pay our bills without borrowing, save and invest prudently for needs we know we’ll have in the future, and have a surplus to give generously.

- We need to be able to have informed conversations with any professional financial planners, advisors, and tax consultants we may be working with to ensure they are always acting in our best interest.

If you’ve been reading those articles, you’d also know that I’ve been making RMDs and QCDs all year long, and now I need to make an end-of-year federal income tax payment to the IRS to satisfy the yearly withholding requirement or pay a penalty. This is an IRS rule.

Some of you may prefer not to do this at one time at the end of the year, as it requires you to send a lump sum at the end of the year instead of having smaller amounts withheld each time to make a taxable IRA or RMD withdrawal. I get that; I did it that way for a while, too.

But then I thought, “Why give the IRS the use of my money all year long when I can keep it in my IRA cash account and earn interest, perhaps 4% plus, and then give them their due at the end of the year?”

I can do this by estimating my tax liability, taking into account recent changes in the OBBBA legislation, and withdrawing and withholding 100% of an amount close to that estimate. I’m less concerned about state taxes, but I’ll still have to account for them.

The recently enacted “One Big Beautiful Bill Act” (OBBBA) is mostly a good thing for retirees, but, as I pointed out in the last article, to the extent it adds to the national debt, it is not particularly good for our grandchildren.

As we’ve seen, for most of us, the OBBBA does not blow up your tax plan; in fact, it will mainly help most of us, especially if you:

- Are taking Required Minimum Distributions (RMDs)

- Make cash (check) charitable distributions,

- Use (or should use) Qualified Charitable Distributions (QCDs), and

- Doing Roth conversions or larger IRA withdrawals.

In this article, we’ll revisit the most important changes for retirees like my wife and me and those of you in a similar situation, as I apply them to my own situation as I try to navigate spending (RMDs), generosity, and satisfying the IRS’s tax withholding requirements.

Using RMDs to pay my taxes

I can use an RMD to cover my federal and state tax liability for the year. Instead of making quarterly estimated payments, I ask Fidelity to withhold taxes directly from an RMD—even 100% of it if needed.

Here’s the advantage: the IRS treats withholding as if it were paid evenly throughout the year, regardless of when it actually occurs. So I can take a December RMD, withhold the full amount for taxes, and still satisfy my annual tax obligations without penalty. This keeps my IRA money invested longer and simplifies tax planning.

There is one wrinkle: the withdrawal itself is taxable.

When I withdraw money from my IRA to pay taxes, that withdrawal is taxable income. This might seem like a problem: if I need to cover my taxes and I’m in the 12% bracket, doesn’t the withdrawal create additional tax, requiring me to withdraw even more?

No, and here’s why: Say before any year-end withholding, my other income creates $6,000 in tax liability. I need to figure out how much to withdraw. Using the formula: $6,000 ÷ (1 – 0.12) = $6,818, I take a $6,818 RMD with 100% withholding.

The $6,818 withdrawal creates $818 in additional tax (at 12%), so my total tax liability is now $6,818 (= $6,000 + $818). My withholding payment is $6,818, so I have a $0 balance due in April.

The $6,818 payment covers both the $6,000 I owed on other income and the $818 tax on the withdrawal itself. There’s no endless tax loop because withholding dollars aren’t taxed—they’re simply payments to the IRS.

When I file my return, I report the $6,818 as both taxable income and as taxes already paid. It feels like the withdrawal “canceled itself out,” but what really happened is it increased my tax bill by $818, which was covered by that same payment.

Here’s the most straightforward way to see it: If I owe $6,000 in taxes and use after-tax savings, I pay $6,000, and I’m done. But if I use an IRA distribution at a 12% rate, I need to withdraw $6,818 to cover $6,000 in taxes. That extra $818 is the “cost” of using pre-tax IRA money instead of after-tax savings.

QCD rules did not change under OBBBA

We can still make QCDs from IRAs, which I started after I reached age 70½. (If you’ve reached that age and aren’t using them, I strongly urge you to consider it.) The maximum rose slightly in 2025 to $108,000 per person, as QCDs (which are indexed for inflation) are expected to continue growing in 2026.

Since my wife and I are 73, our QCDs can count toward our RMDs. I’ve mentioned this before, but this is a really good thing, and here’s why.

In this new environment, I believe that QCDs are often the best giving tool for retirees. First, the QCDs never show up in your AGI—you deduct them from the RMD totals on your 1099 “above the line.” (A regular IRA withdrawal increases AGI and then maybe gets offset by a Schedule A deduction if you itemize—I discuss the new floors and caps in the next section). Since many retirees don’t itemize, that doesn’t help them tax-wise. Fortunately, QCDs bypass the 0.5% charitable floor and 35% cap.

There’s even more good news about QCDs: they help protect other income-based thresholds because they lower your AGI. That can help reduce taxation of Social Security, IRMAA surcharges on Medicare premiums, phaseouts of the new senior deduction and SALT deduction, and other income-based gotchas.

For serious givers in retirement, OBBBA slightly tilts charitable giving strategies toward “Give from your IRA (QCD)” rather than “Take extra IRA income and then itemize and deduct on Schedule A.” From a stewardship standpoint, that’s good news: you can redirect pre-tax dollars to kingdom work while also reducing the tax bite.

An eye on the new charitable giving rules in 2026

Most of my charitable giving in 2025 has been via QCDs, but for all of you under age 70½, that’s not the case. So, it’s important to remember that, starting next year, if you itemize, you only get a deduction for charitable gifts above 0.5% of your AGI (your “floor”).

Beginning in 2026, taxpayers in the 37% tax bracket must reduce their itemized deductions by “2/37.” This doesn’t shrink the deduction itself, but it reduces its tax value: every $1 of itemized deductions will lower federal taxes by 35 cents instead of 37 cents.

In short, the deduction still appears in full on Schedule A, but it simply saves less tax. This change makes strategies like Qualified Charitable Distributions (QCDs) even more attractive for high-income, generous retirees.

The OBBBA is good news for all charitable givers (whether via QCDs or not): It’s the new above-the-line charitable deduction for non-itemizers: up to $2,000 (married) for cash gifts starting in 2026 (so no direct effects in 2025, other than you may to delay until 2026 to make cash contributions you were going to make it late 2025).

Taking the new “senior deduction” (2025–2028)

This one begins this year (2025). Each person age 65 or older can claim an extra $6,000 ($12,000 for a married couple if both are 65+), on top of the usual standard deduction. Since my wife and I are both in our 70s, we’ll take this deduction. (And you should too!)

This deduction phases out as modified adjusted gross income (MAGI) rises above $150,000 (married).

SALT cap gets bigger (for a while) but doesn’t do me any good

The deduction limit for state and local taxes (SALT) jumps from $10,000 to $40,000 starting in 2025, then gradually phases out for very high incomes and eventually snaps back to $10,000 in 2030.

This mainly helps retirees in high-tax states with large property or state income tax bills who already itemize. I pay state income tax and state property taxes, so this might affect me if I itemize.

Other deductions

There are some other deductions that I (and you) can take. Some are new with the OBBBA, such as the new “senior deduction” (and no, that doesn’t mean “no taxes on Social Security” even though people keep saying it) of $6,000 per person. That’s a generous deduction, times two ($12,000), for couples age 65 and older.

There’s also no tax on up to $25,000 of tip income (doesn’t apply to us), up to $25,000 of overtime income (ditto), or up to $10,000 of interest on certain new-car loans (nope, not that one either). In fact, most retirees won’t see overtime or tip deductions, but the senior deduction will matter to everyone 65 and older.

Finally, home energy credits end after 2025. Energy-efficiency credits for items such as windows, doors, insulation, and heat pumps remain available in 2025 and can provide up to $3,200 in deductions for some projects. Still, many clean-energy credits end after December 31, 2025. So, get your credits while they’re hot if you have a project like that in mind.

My estimating process

Instead of showing you a spreadsheet, I’ll step you through the relatively simple process of estimating my withholding amount and where I go from here:

- Sum up my RMDs for 2025; they are part of our Adjusted Gross Income (AGI).

- Sum up my Qualified Charitable Distributions (QCDs) for 2025.

- Reduce my RMDs by the sum of our QCDs; this effectively reduces our AGI “above the line.”

- Sum up our Social Security (SS) income; it counts as part of our AGI.

- Determine Social Security provisional income and the amount taxable. That will be the final Social Security amount included in our AGI.

- Calculate our AGI (= Taxable RMDs plus Taxable SS Income)

- Sum up all deductions (= Standard Deduction for Married Filing Jointly Over Age 65 plus Senior Bonus of $6,000 per person)

- Calculate taxable income (= AGI minus all deductions; include any cash charitable contributions, i.e., non-QCDs)

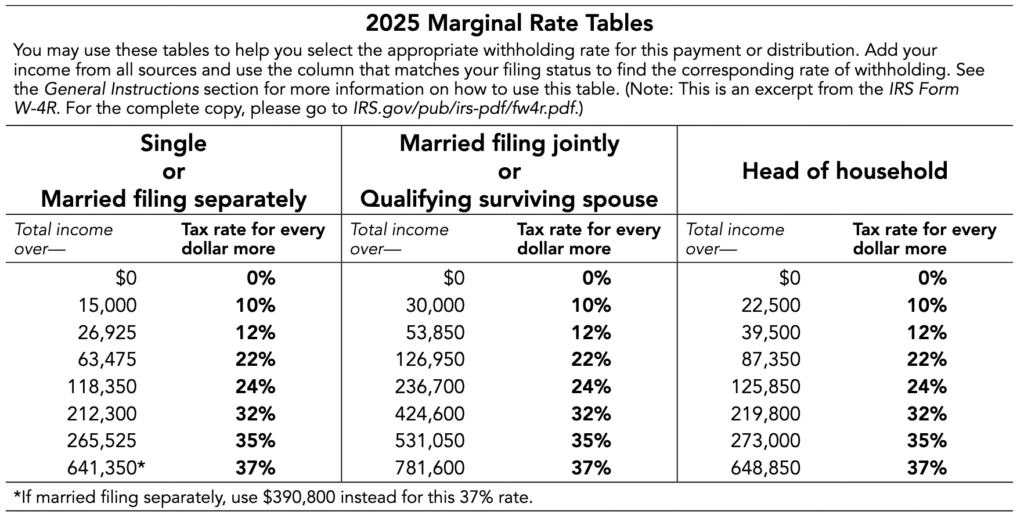

- Calculate income tax owed using the tax bracket table for MFJ over 65.

- Take 90% of my total tax liability and send it to the IRS (by withdrawing from my IRA and indicating 100% goes to taxes).

- Rest easy until April, when I’ll have to pay any difference between what I withheld and my final tax bill.

When I did this, making some estimates about withdrawals and QCDs before the end of the year, I found that I am in the 12% marginal tax bracket but owe tax equivalent to 4.75% of my gross income (i.e., before any adjustments). I can use that as a guideline for withholding.

Final things to consider

To avoid penalties, I generally need to withhold at least 90% of my total current-year tax liability or 100% of my previous-year tax liability (110% if my adjusted gross income was over $75,000).

If I estimate that my total tax will be $10,000, I need to withhold/pay at least $9,000 before year-end. Note that my tax liability is based on taxable income (after deductions), not gross income.

(I didn’t show all the specific numbers, but as I’ve written about before, making QCDs and taking all the deductions we’re entitled to makes all the difference when it comes to our average tax rate.)

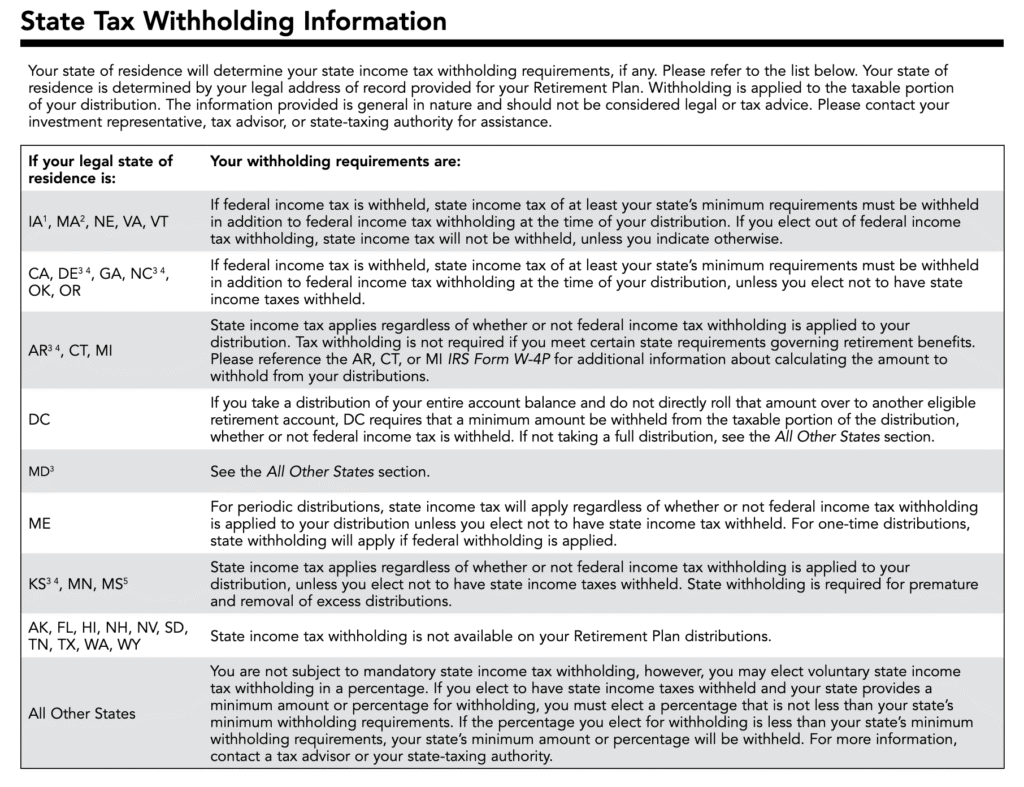

But that’s not all. I also have to consider my state (NC) income tax. Here’s a handy reference from Fidelity that lists the state withholding requirements:

As you can see, in my state, “If federal income tax is withheld, state income tax of at least [my] state’s minimum requirements [which is 4%] must be withheld at time of your distribution, unless you elect not to have state income taxes withheld.”

North Carolina requires automatic 4% state withholding on an IRA distribution when federal withholding is applied. This doesn’t mean I owe 4%—it’s just a prepayment. I can either let them withhold the 4% now (a conservative approach) or check the box to opt out and pay my actual NC tax liability when I file (keeping more money working for me longer).

Since I prefer to delay payments, I’ll opt out of state withholding and pay my actual NC tax in April.

Done for now

Okay, that’s all there is to it, until next year when I have to firm all this up on my tax returns. So, maybe less about taxes for the next few months; I assume you might appreciate that.