This article is part of the Biblically-Informed Framework for Retirement Stewardship (BIFRS). It was initially published in May 2018 and updated in January 2026.

If you have followed this blog for very long, you may have noticed that I don’t write much about investing. There are several reasons for that, not the least of which is that I am not a professional financial advisor and I’m not qualified to make recommendations to other people about how to invest their money – certainly not regarding specific stocks, bonds, or mutual funds or other investments.

Another reason is that I think starting to practice wise biblical stewardship by budgeting, giving, and saving as soon as you receive your first paycheck is more important than how you invest, provided you aren’t taking unnecessary risks. Starting to save sooner rather than later and on a regular basis thereafter has a more significant impact on your ability to retire with dignity than whether you invest in Stock A or B or Mutual Fund C or D. In fact, those who wait too long and then have to play catch-up can be tempted to take on more risk than they should as they approach retirement.

Please don’t misunderstand; I am not minimizing the impact that wise investing can have, especially over the long term. Making sound investment decisions involves wisdom, some knowledge, and understanding, whether you are working with a professional financial advisor or not.

Some of you may be knowledgeable, experienced investors, but others may not be. So, I thought it might be helpful to discuss some investing basics related to retirement. In addition to general information about investing, I will also share a little about some of my investments, but for illustrative purposes only – they may not be right for you. Because the main goal of this blog is to inform, educate, and inspire, you should never take anything I write as professional financial advice, and you certainly should not assume that because I like a particular investment, it would be appropriate for you.

Investing phases

Investing for retirement can be viewed as two major phases: the accumulation phase and the distribution phase. These tend to be stage-of-life specific. The former is usually from age 25 to 65, and the latter from age 65 and beyond, but the exact timing will vary by individual.

The accumulation phase is the time leading up to retirement, when you are saving and investing to accumulate money to live on when the time comes. The distribution phase is when you are in retirement and are living off your savings, usually in the form of regular distributions to replace some portion of the income you had while working. In most cases, you will be supplementing Social Security and perhaps a pension to provide the income you need in retirement.

For most people, the accumulation phase begins in their 20s or 30s (sometimes later) and continues into their 60s or 70s. That’s a period of 30 or 40 years, which is very long. I didn’t start saving for retirement until I was in my 30s, and even then, I saved relatively little. If you retire at age 68 and live to age 88, you will be in the distribution phase for 20 years, which is also a pretty long time. Estimated lifespans are increasing, which puts a greater burden on us to save and invest wisely to ensure we don’t run out of money before we run out of life.

In these three articles on investing for retirement, I will discuss some strategies you might want to consider if you are still in the accumulation phase. I will offer my thoughts on some of them and give some personal examples. These may pertain to people in their 20s through their 60s or 70s. As a retiree now, I can also offer some reflections on how these strategies have played out in actual practice during my seven years of retirement.

My investing background (or lack thereof)

I have been an investor of sorts for about four decades now. Not professionally, just in my retirement accounts. I have also done a fair amount of reading and studying on the subject. (You can find some recommendations on the resources page of this blog.) But I have never traded stocks. In fact, I’ve never owned an individual stock except for shares given to me by my employer. It’s not that I think buying and selling individual stocks is wrong; it just wasn’t for me. I didn’t want to devote the time and attention to it, nor did I think I had the expertise to do it well. So I stuck with mutual funds and, more recently, Exchange Traded Funds (ETFs).

Like most people, I have made some mistakes and lost money. Not just because an investment lost value (that is what they sometimes do), but because I sold at the wrong time. I have also made a few good investment decisions. Fortunately, despite bubbles and crashes along the way, the stock and bond markets have provided solid long-term returns over the past several decades.

Let’s look at the numbers. The total return for the S&P 500 (500 largest companies in the U.S.) from January 1980 through December 2024 was approximately 4,800 percent, which equates to an average annual return of around 11.3 percent (with dividends reinvested). Of course, these numbers are not adjusted for inflation, but if you factor it in, the real gains are closer to 7.5-8.0 percent annually. Even in more recent periods, from January 2000 through December 2024, the S&P 500 returned approximately 9.4 percent annually despite the dot-com crash and the 2008 financial crisis. And from 2020-2024, despite the COVID-19 crash, the average annual return has been around 13.5 percent.

Unfortunately, I was never fully invested in the S&P 500. I was always too conservative for that. In spite of those big numbers, there were also periods of white-knuckle drops (it’s easy to forget about those). I have generally been cautious and mostly held a ‘balanced’ portfolio, meaning it stayed in the 60/40 to 70/30 percent ratio of stocks to bonds and cash. My investment mix has changed over the years, and I have gradually become more conservative as I’ve gotten closer to retirement; my current ratio is 35/55/10 (stocks/bonds/cash), reflecting my position as a retiree focused more on income and preservation than growth. I try to consistently follow a set of core principles when it comes to investing, which I believe have biblical support.

I have seen a lot of market ups and downs in my own investing lifetime: The “Stagflation” bust of 1980-82 (27.8% decline); the “Black Monday” crash of 1987 (22.6% decline); the “Dot Com” crash of 2002 (49.1%); the popping of the Real Estate Bubble in 2008 (the S&P 500 lost 56.5%); and the COVID-19 crash of March 2020 (34% decline in just 33 days). Like many people, I saw my 401 (k) lose almost 40 percent from 2007 to 2009. I also happened to be working at one of the large banks (Wachovia) that failed in 2008, which affected me, other employees, and clients in many negative ways. (I was an IT guy, so they can’t blame me.)

Having now lived through the COVID-19 crash as a retiree, I can attest that market volatility feels very different when you’re in the distribution phase than when you’re in accumulation. The rapid recovery was welcome, but the experience reinforced the importance of maintaining adequate cash reserves and not being forced to sell during a downturn.

Younger investors who have only experienced the robust bull markets of recent years are in for a surprise when the next major correction comes. They may think they have a good investing plan and know their risk tolerance, but as a famous world champion boxer once said: “Everyone has a plan until they get punched in the face.”

I know people who got out of the markets completely in 2008-2009 and never got back in. Some have regrets about that, given the strong recovery since 2010. I was tempted, but I didn’t bail out completely as I knew I had at least 10 or 15 years to retirement. Plus, I had already been through a couple of previous bubbles, although none as bad as that one. I do remember backing off my stock allocation at some point – about midway down the slide, I think – and then I slowly got back in, albeit at a lower level than I was initially.

As a retiree now, I remain invested in stocks (about 30% of my portfolio) because they provide growth that helps mitigate the effects of inflation on my fixed-income sources. Capital preservation and income are my primary focuses, but complete abandonment of equities would leave me vulnerable to the long-term erosion of purchasing power.

Wise investing is biblical

Retirement may be overrated, but the reality is that most of us will ‘retire’ from our full-time job at some point in our lives. Even if you plan to work as long as you are able, you may eventually need to stop for one reason or another. Therefore, saving is important, but how you invest – both before and during retirement – will also have a significant impact on what you have to live on when you are retired. If you think it is wise to save for anticipated needs in the future, including retirement, then how should you invest your savings? Perhaps you wonder whether you should invest at all, or whether it would be better to keep the money safely squirreled away in an insured bank deposit account. I understand that sentiment.

I certainly appreciate a hesitancy to put money in the stock market. But although the financial markets carry some risk, the Bible makes a distinction between investing and gambling. The biblical model is one based on stewardship, which means making decisions with accountability to God for the money he gives us to manage (Matt. 25:14-30; Lk.16:1-12,19:11-27).

Investing involves some prudent risk-taking, but the money is usually put to some productive use. Although there is mention in the Bible of some decision-making by ‘random’ chance (Num.33:54; Pr.18:18; Acts 1:26), there is no event that is outside God’s sovereign will (Prov.16:33). Also, while there is no specific biblical teaching on gambling for money per se, gains from it don’t involve legitimate work or effort combined with risk (Pr.14:23). The Bible teaches that chasing after easy wealth ultimately leads to poverty as the house always wins in the end (Pr.28:19-20).

When it comes to investing in things like company stock, the Bible seems to sanction some risk-taking and associated profit-sharing if done wisely (Pr.31:10-31; Ecc.11:1-6). Even in ancient times, people would buy an interest in large, high-cost, high-risk projects and then share in the profits or losses (for example, shipbuilding). But as history has taught us, gains from such investments are always uncertain.

When we unwisely bet on a sure thing in the stock market, we are gambling on future events (hedge funds do this with borrowed money), which is speculative and presumptive on the future, both of which are discouraged in Scripture. The Bible teaches that we must be wise and humble in our attitude towards the future (Pr.27:1; Is.56:11,12) and that it is foolish to presume upon it (Lk.12:16-21; Jam.4:13-17). God laughs at the plans of men (Psalm 2:4).

Lending and debt are interesting topics in the Bible. Lending is encouraged under certain circumstances, and debt is not prohibited per se, but it is discouraged and must be repaid. Despite some Old Testament prohibitions against exacting interest (except from foreigners – Dt.23:19-20), more recently, the interest on capital loans for business has been considered reasonable and acceptable by the Church. However, lending for personal day-to-day subsistence, such as payday loans and similar products, is frowned upon as uncharitable and even predatory.

Investing for retirement framework

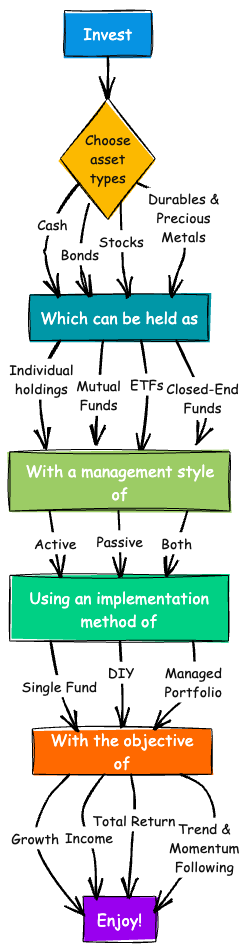

As a former IT Architect, I like (and draw) diagrams. I thought it might help frame this discussion to do one for investing, and I will be working through it from top to bottom in these three articles. You may already be familiar with many of these terms and concepts, but may not have thought about how they all fit together. It is an overall investing framework that can be applied to both the accumulation and distribution phases. Because our goals tend to change as we age, most of the differentiation between the two comes in the ‘investing objective’ section at the very bottom.

In this article, I will discuss the first section: choosing the asset types you want to invest in. In the second, I will discuss the different ways you can hold them and the difference between active and passive management. The third article in the series will focus on the rest of the framework: ways to implement and different investment goals and strategies.

Choosing your assets

Before you consider different investing and asset management styles, you first need to understand the various asset types, their characteristics, and their relative risks, and decide which ones you may want to hold in your retirement accounts.

Cash

Because most of us receive our income in cash, this is where we start. There are various ways to hold cash. You can put it in your mattress or a hole in the ground, but that is not advised (see Matt.25:24-28). You will have a zero or negative return due to inflation. You can also hold dollars in various types of financial institution accounts (bank deposits, credit union deposits, etc.).

Interest rates on cash holdings have changed significantly since this article was originally written. Savings accounts and certificates of deposit now pay considerably more interest than in the 2010s. As of early 2026, high-yield savings accounts are paying 4.0-5.0 percent, and CDs are yielding between 4.0-5.1 percent depending on term and institution. Money market funds are also in the 4.0-5.0 percent range. These rates represent a dramatic improvement over the near-zero rates of the 2010s, though they fluctuate with Federal Reserve policy and economic conditions. Cash savings can also benefit others as it gives banks the money they need to lend for things like mortgages. Bank deposits also carry low risk due to FDIC (U.S. government) insurance (up to $250K per depositor, per institution).

Holding some cash is always a good idea, especially as you approach or enter retirement. But given the long-term inflation risk, we need to look elsewhere for better options when investing for decades.

Bonds

Investing in bonds is a way of loaning money to businesses or governments. You can buy company bonds (debt issued to fund company operations and expansion) or government bonds (government debt to support everything from defense to welfare) with varying returns based on term, assigned risk, and market interest rates when they are issued. As of early 2026, most investment-grade bonds are yielding in the 3.5 to 5.0 percent range, which is considerably higher than the ultra-low rates of the 2010s but lower than the historical peaks of previous decades. Many years ago, I bought a twenty-year ‘zero-coupon (treasury) bond’ with an effective annual return of 12 percent! Of course, mortgage interest rates were in the 14 to 16 percent range at the time.

Company bonds are viewed as carrying a higher risk than government bonds. Bonds have interest rate and default risks. The longer the term or the greater the risk of default, the higher the interest paid to bondholders. Non-U.S. government debt is considered riskier than U.S. Treasury Bonds, which are considered safer than company bonds. Bonds are considered riskier than cash (because companies can default), but safer than stocks. That’s why so many people diversify their stock holdings with bonds. I currently hold over 60 percent bond funds and cash in my IRA, reflecting my conservative stance as a retiree focused on capital preservation and income generation.

Company stock

When you buy a stock, you own a share of a company, called equity. Stock ownership is one of the most productive uses of your investment dollars, as it helps companies employ people and provide goods and services. Equity entitles you to a return based on the company’s profit and earnings distribution policy. However, these returns are not guaranteed; they can vary significantly from year to year. Larger, stable companies that have a history of paying dividends are considered less risky than newer, highly leveraged companies, which tend to be more speculative. Domestic companies are usually less risky than internationals (due to volatile political and economic environments), with emerging markets being the riskiest. Stocks are generally viewed as riskier than bonds because, if the company fails, you could lose all your money. However, investing in stocks is not the same as gambling. If you buy a lottery ticket, the probability of losing your money is greater than 99 percent (and the odds of winning the Powerball Lottery are a staggering 1 in 300 million!).

Real Estate

You could buy residential or commercial rental properties or mutual funds that invest in them. You may also consider your residence an ‘investment,’ but because mortgages involve high leverage, it’s better to view it as a way to provide for dependents and hospitality. Vacation homes may or may not be good investments, as they are usually highly leveraged and dependent on high rents during peak periods. Real estate tends to be cyclical and subject to interest rate risk and economic risk. It can also have high maintenance and administrative overhead,d which can detract from profits.

Small Business

This is not shown on the framework, and you may not think of owning a small business as an investment, but it can be. A small business can earn income that may increase in value before you retire, and can continue to provide income or be sold to provide income in retirement. Many small business owners also invest a portion of their income for retirement.

Durables and precious metals

These include antiques, jewelry, and art, which can have practical uses and provide enjoyment, but they are not always good investments. Precious metals, such as gold and silver, may help mitigate some of the risks of inflation or economic breakdown, but tend to be highly speculative as investments due to high volatility. Holding some of these provides diversification to an investment portfolio, but holding too much can tend toward hoarding as the money isn’t being put to productive use. Notice the fear-motivation tactics behind many of the ads you see for buying gold on TV.

To be continued…

As you can see, there are many options for investing your hard-earned dollars. In the next article, we’ll discuss some of the ways you can hold your investments, as well as active versus passive management styles.