In the previous article, I stated that, to many people, investing seems like gambling. You give your money to a company, and they invest it in their business. There is a good chance you’ll make money, but also a chance you’ll lose. They could even lose it all if they go bankrupt. Sounds like gambling, doesn’t it (except for the “good” chance part)?

But the truth is, investing isn’t gambling. Why not? Because, unlike day-trading, it involves informed and prudent risk-taking, rather than taking blind chances to make a quick buck. The Bible doesn’t prohibit risk-taking and business profit-sharing; trade and risk-taking are commended in Scripture if done wisely (Ecclesiastes 11:1-6). But remember, profit is uncertain; there are no “sure things” when it comes to business and investing.

Investing, then, is a good use of some of our money. I wrote this in an article for The Gospel Coalition a few years ago:

“Investing isn’t stock trading. It’s not about betting the farm on a hot tip from your brother-in-law. Such speculating amounts to gambling on future events, and most of the time you lose more than you gain (Proverbs 28:19; 1 Timothy 6:10). It’s about putting money into real businesses that employ people and deliver products or services to customers. Hopefully, the companies we invest in do well and provide a return commensurate with our investment (Proverbs. 31:10–31; Ecclesastes. 11:1–6).”

But investing carries risk. Notice that I wrote, “hopefully, the companies…do well.” They don’t always, nor does the market as a whole. In case you haven’t noticed, for investors, the last few years have been bizarre and unsettling at times as the financial markets—both stocks and bonds—have been very volatile (i.e., lots of ups and downs).

Despite its volatility, which is what gives investors heartburn, the stock market (S&P 500) has been down 20% or more for a year only 15 times since 1926. It has gone up about 75% of the time, and most of the time by a lot—it’s been up more than ten percent 56 percent of the time.

That is why the average return for the index is around 10%. But the primary lesson is this: Stocks are risky, so to get long-term market returns, you have to take losses along the way. The questions are: 1) Do you understand the risks? And 2) are you comfortable taking them?

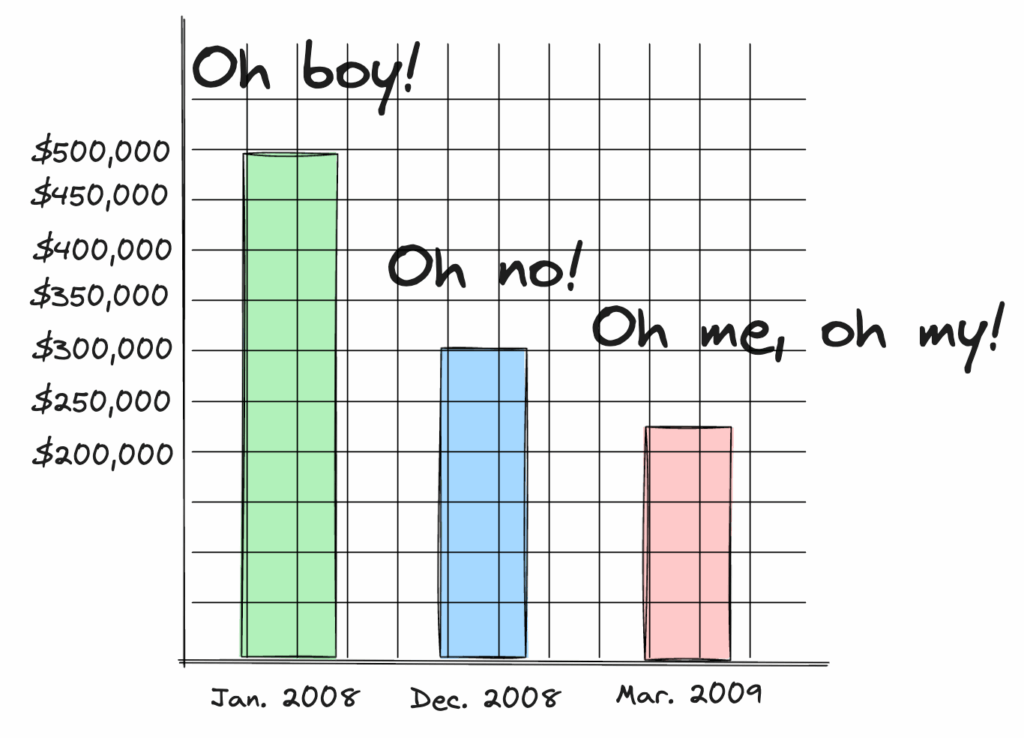

Take a look at this slide, which presents a zoomed-in view of the stock market (S&P 500) and what an account balance of $500,000 fully invested in it would have looked like during the 2008-2009 financial crisis:

As you can see, at one point it was down over 50%! It was a scary time for investors (especially people like me who were about 10 years or so from retirement age).

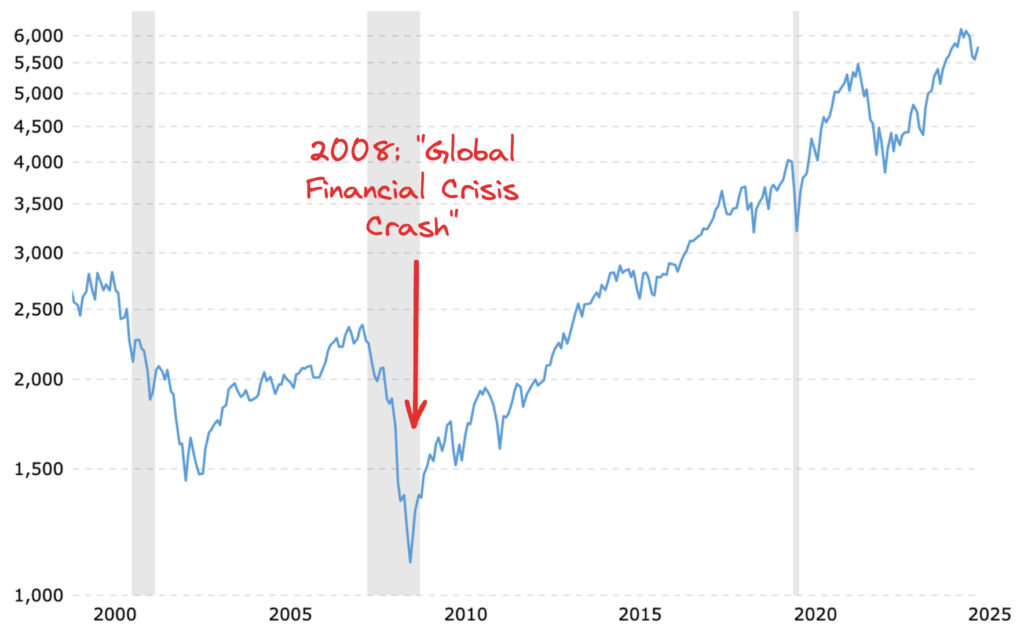

Believe me, an event like that will test your risk tolerance. Those who sold out of the market in 2008 or 2009 (and many did—it felt like the end of the world) and did not reinvest pretty soon after would have missed out on the biggest stock market rallies in history.

This illustrates what happened in the years that followed:

Here’s a hard truth you need to hear: You will sometimes lose your shirt in the stock market (or it will feel like it). I “lost” a lot of money in 2008-2009, and I would be dishonest if I said it didn’t hurt. Losing money in real life is a lot harder than it is hypothetically. The good news is that those who rode out the storm ultimately came out okay. In fact, as the chart above shows, it is better than just okay.

If you had invested $250,000 in the S&P 500 at the end of 2009, your investment would have grown substantially by May 2025, assuming all dividends were reinvested. Its value in May 2025 would be approximately $1.45 million based on an estimated annualized return of 12% over 15.5 years. That’s a total cumulative return of 479%, the result of many years of good compound returns.

But remember: there’s no guarantee that the next few decades are going to be like the last.

Losing your shirt in the market is a part of the normal cycle of investing. As one famous investing author, William Bernstein, put it, “it is the duty of investors to lose money from time to time.” But with enough experience and practice at losing smaller amounts of money, losing tens, hundreds, thousands, and even tens or hundreds of thousands of dollars should not elicit panic.

It won’t feel good; it never feels good to watch one’s portfolio go down that much, but it’s a normal part of the process, and the prudent response is to stay the course.

Markets are highly volatile in the short term. That’s a fact. However, you’re not investing for the short term; you’re investing for the long term over the next several decades. As a result, day-to-day, week-to-week, and month-to-month swings in stock prices should be irrelevant to you. Ignore the financial press like CNBC and stock market pundits who spout nonsense. Trust me, ignoring most financial news will make you a much happier and wealthier investor.

One of the biggest mistakes that risk-averse investors make is trying to time the market. I showed you what happened after the crash of 2008-09. Trying to time the peaks and troughs of the market is a fool’s errand. Mr. Market will outsmart you almost 100% of the time.

You can avoid this mistake by simply investing your savings gradually over time (called “dollar cost averaging,” which means that you’ll sometimes purchase stocks “on sale”). Then, stay calm and refrain from selling unless absolutely necessary.

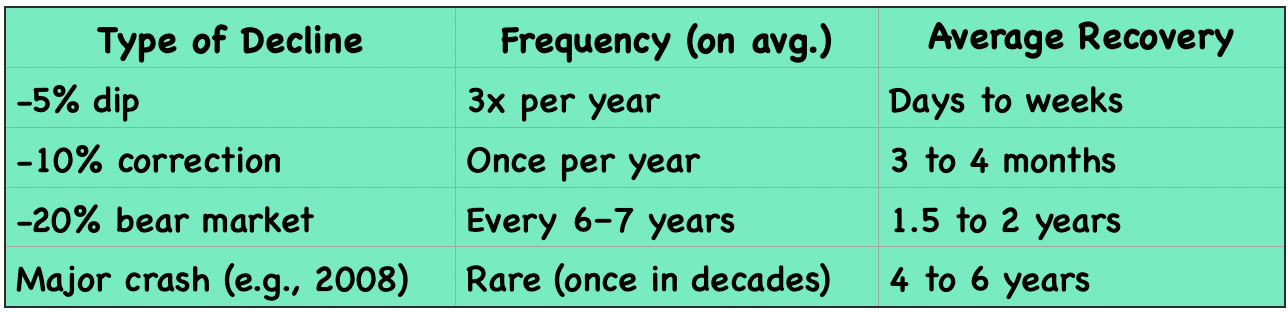

The chart below shows the futility of trying to time the market. Notice the frequency of declines of 10% or less; they happen on average several times a year, but the average recovery time can be days, weeks, or sometimes months. (Most importantly, it does eventually recover.) How can you predict any of that, much less optimally timing your exits and re-entries?

The worst thing you can do is to stay out of stock altogether because of fear. You’re free to do that, but that doesn’t mean it’s wise. Another unwise pursuit is taking the “Robinhood” app route and experimenting with individual stocks and trading stock options. Only do that with money you can afford to lose, as you almost surely will.

Investing in the stock market carries some risk, but it can be riskier not to. To illustrate, let’s say you put $10k into the market, but pulled it out days later when the market went down. You now face an uphill battle when trying to grow a long-term portfolio. Losing 10% of a $10,000 investment portfolio creates a painful short-term loss of $1,000. But what’s more concerning is the long-term opportunity cost of holding only cash.

A decade of 10% average annual returns with a beginning balance of $10,000 would have resulted in an ending balance of ~$26,000. By not investing, you still have your $10,000, but you’ve missed out on the ~$16,000 (=$10000 * 1.1010 – $10000) in potential growth by parking your cash on the sidelines.

It’s easy to lose sight of that when being slapped in the face by an immediate $1,000 investment loss in a given day and the constant flash of stock tickers on our screens. Volatile stock tickers distract investors from what matters: the magic of compound interest when zooming out over multi-decade horizons (which I’ll discuss in the following article).

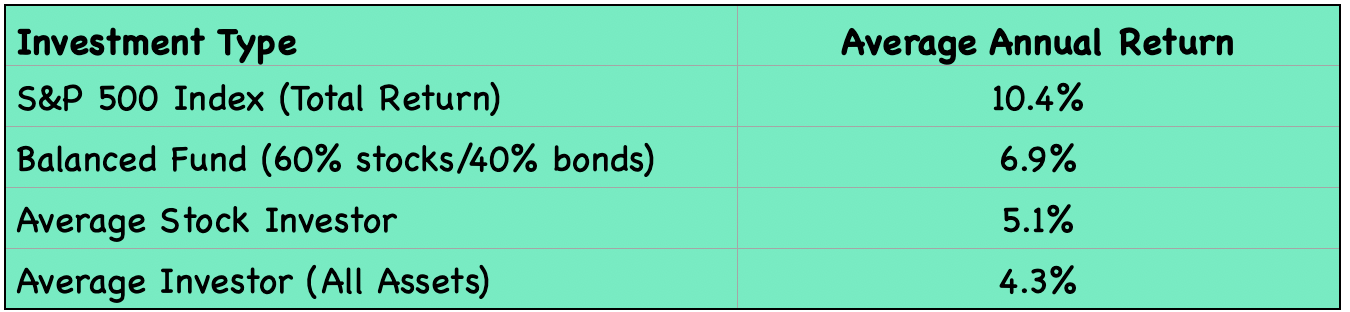

This chart illustrates how individual investors performed over the last 20 years in comparison to a simple stock index or balanced fund:

Notably, despite all their efforts, the average stock investor earned only 50% of the return of the S&P 500 over the period (5.1% versus 10.4%).

This does not mean that you should never sell! There are times when it makes sense. The problem is that we buy and sell for the wrong reasons at the wrong times, often due to our emotions. The stock market is cyclic, and regular investors tend to buy when it’s rising and sell when it’s falling. Over time, that results in lower returns.

What I’ve been talking about throughout this article, without naming them, are two fundamental concepts: risk tolerance vs. risk capacity. Risk tolerance is emotional: how much market decline you think you can handle. (I sometimes refer to this as the “sleep at night factor.”) Risk capacity is financial: how much risk your time horizon actually allows. These two are interrelated. If you’re decades away from needing the money, your risk capacity is high, even if your tolerance feels low. Still, whether you are willing to take the risk will probably have more to do with your tolerance than your capacity.

A good way to assess your risk tolerance is to ask yourself, “How much money can I afford to lose”? Your answer will fall somewhere between “I can’t afford to lose anything and I’m okay losing it all (though I’d rather not).” Most of us land somewhere in the middle, depending on how much we’ve saved and how close we are to needing the money (our risk capacity).

Some 30-year-old investors with decades ahead of them might shrug off a 30, 40, or even 50 percent drop, confident the market will recover (as it usually does). But a 55-year-old with just 5 to 10 years to retirement? That same 30% decline could feel catastrophic (that was the situation I was in back in 2008; I retired in 2019).

We’ll discuss how all this applies to your investing decisions in a future article on asset allocation. My goal is to convince you that you can afford to take some risk, which will hopefully help you with your risk tolerance if you are highly risk-averse.

For reflection: I’ve said several times that the stock market can be scary sometimes and that it has “crashed” before and will probably “crash again.” That makes it sound like a big casino where you place bets. Yes, there are risks, but over time, the rewards outweigh them. What do you feel when you think about investing in stocks? If you experience either fear or greed, you’re coming at it in the wrong way. Better to do it humbly and wisely—understanding the risks, but also the potential rewards—and build wealth slowly and carefully over time.

Verse: “Wealth gained hastily will dwindle, but whoever gathers little by little will increase it” (Proverbs 13:11, ESV).

Resources:

My articles from RetirementStewardship.com: