Once you decide that you want to save and invest, and have a general understanding of your risk tolerance and risk capacity, you’re ready to think about specific asset types. These will become the foundation of your investment portfolio.

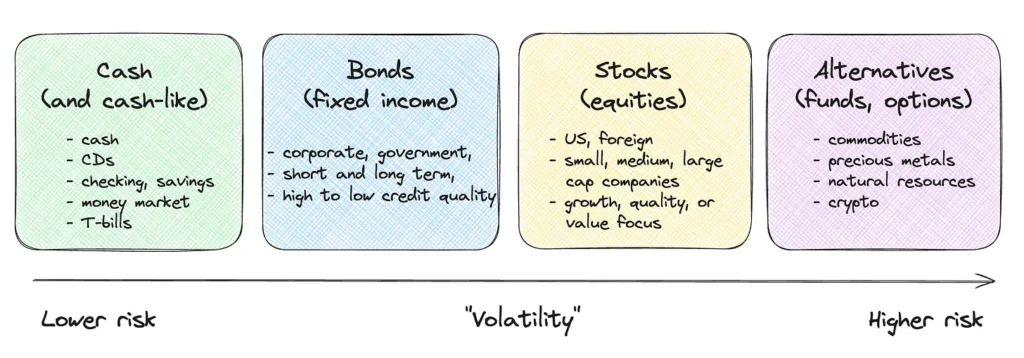

The graphic below describes the major asset categories. Think of them as the basic building blocks of your investment portfolio. You will have some, or more or less, of them, depending on your saving and investing goals, as well as your risk tolerance and risk capacity. Most of you in your 20s and 30s will (and should) be focused on stocks, but you need to know a little about the others, also.

First, it’s always good to have some CASH on hand. The rate of return on money stuffed under your mattress is 0% (negative if accounting for inflation). However, you can put it in the bank, in a savings account, a certificate of deposit (CD), or a brokerage money market and earn interest. That’s a better option than your mattress; it’s a good place for your emergency fund, but not your retirement account. It can benefit others because banks loan money, and this multiplies several times over. Plus, the risk is low—the US government insures some bank accounts.

Next up are BONDs. A bond is a loan made by an investor (you) to a company or government agency. The value of bonds lies in the fact that the borrower agrees to pay interest to the lender. The rate of return is usually fixed but can vary according to the general interest rates in the economy and the term of the loan. Investing in bonds helps businesses and the government function. Bonds are generally low risk, and even if a business loses money, it still has to pay you. Sometimes, companies do default on the loans. If you buy an individual bond, the money remains yours.

Then there are STOCKS. A stock (sometimes referred to as “equity”) is a piece of ownership in a company. Their value lies in the fact that companies (usually) earn profits. Those profits are either 1) distributed to shareholders as a payment called a “dividend,” or 2) reinvested to grow the company, which will hopefully increase the company’s value in the future. However, none of this is “guaranteed,” and returns are unknown; we can only know how a company has done in the past. Over a 50-year average, publicly traded stocks have increased an average of about 10% a year, depending on how you measure it, but with much variation from year to year. Still, in some years, people make a lot of money in stocks, while in others, they lose, sometimes a significant amount.

Finally, there is a large category of investments which I’ll call “ALTERNATIVE ASSETS.” It includes items such as precious metals, natural resources, and commodities. Gold and Crypto are in this category. Investing in these is highly speculative, so it's generally something that the average person should probably avoid. If you want to dip your toe in them, make sure you research them thoroughly.

You can invest in individual stocks and bonds (the smallest building blocks). However, most individual investors, especially young, inexperienced ones, can’t “beat the market.” By that, I mean investing in individual stocks that outperform the overall market over time. Hundreds of research studies have concluded this. The best thing you can do to maximize your real returns is to manage the two levers in the financial life equation (FLE) that you have some control over: investment management fees and taxes.

It’s better to own “baskets” of stocks and bonds, known as Mutual Funds or Exchange Traded Funds (ETFs). These baskets are simply a collection of securities—sometimes hundreds or even thousands of them—that have been chosen by a professional investor or company (known as a “fund manager”). Many mutual funds are known as “actively managed” funds because their managers seek investments that they believe will yield above-average returns.

To minimize investment management fees, you can avoid high-cost financial advisors (which I consider anything over 1.0% of assets under management, or AUM), as well as high-cost actively managed mutual funds (over .50%).

Mostly, it’s better to buy a fund that captures the market return at a rock-bottom investment management fee. This product is known as an Index Fund (a fund that is “passively managed” and tracks the performance of a specific index, such as the S&P 500, at a very low cost). Index funds are passively managed, meaning they are designed to mimic the performance of a given index. In investing, indexes serve as indicators that represent the value of a specific group of investments.

For example, one of the most well-known is the S&P 500, which tracks the value of 500 of the largest companies in the U.S. Therefore, an S&P index fund is a mutual fund that owns shares of each of the companies in the S&P 500 and which should closely mimic the performance of the S&P 500 index. Some indices track just about everything. Fortunately, you only need to know about a handful of them to create a well-diversified portfolio (more on that in a bit).

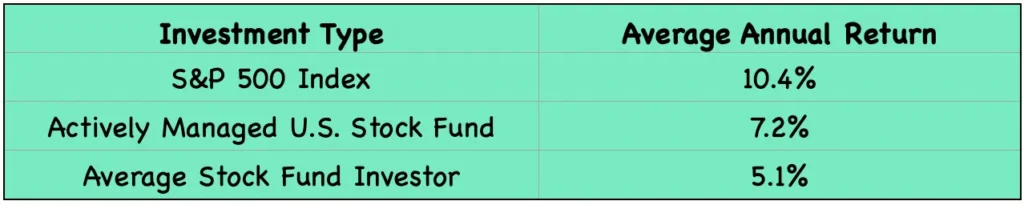

If you’re interested in some relevant performance data, the chart below shows the 20-year performance data of three U.S. investment strategies (ending 2024).

Source: Dalbar, Inc., Quantitative Analysis of Investor Behavior (QAIB), 2024.

It illustrates the dramatic difference between what the average mutual fund investor earns and what can be achieved by simply investing in an S&P 500 Index Fund. This disparity is not primarily due to performance (as shown by the second line), but rather to behavior—the tendency that individual investors have to buy and sell too frequently and at the wrong times.

Perhaps you’re thinking, “But I don’t want to miss out on owning the hot stocks, so isn’t something like owning the S&P 500 Index spread my money too thin across too many losers.” Well, I own a Fidelity Investments S&P 500 Index Fund (FXAIX) in my Roth IRA. For illustrative purposes, here’s the current breakdown of what a $100 investment in the top ten S&P 500 stocks would be in proportion to their size (known as “market capitalization” based on April 2025 data):

- AAPL Apple Inc. 6.75% ⇒ $6.75

- MSFT Microsoft Corporation 6.21% ⇒ $6.21

- NVDA NVIDIA Corporation 5.64% ⇒ $5.64

- AMZN Amazon.com, Inc. 3.68% ⇒ $3.68

- META Meta Platforms, Inc. 2.54% ⇒ $2.54

- BRK-B Berkshire Hathaway Inc. 2.07% ⇒ $2.07

- GOOGL Alphabet Inc. 1.96% ⇒ $1.96

- AVGO Broadcom Inc. 1.91% ⇒$1.91

- TSLA Tesla, Inc. 1.67% ⇒ $1.67

- GOOG Alphabet Inc. 1.61% ⇒ $1.61

FXAIX’s top ten stocks make up approximately 34% of the fund. But there are 490 other stocks in the fund, so, with this one index fund, if you invest $100, you can own the top 500 largest companies in the U.S. for a cost of 0.015% per year (the “expense ratio”), which translates into 1.5 cents (=100*.00015)!

Broad index funds are a fantastic financial technological innovation that has enabled ordinary people like you and me to capture the returns of the largest companies in the U.S. economy for essentially $0 in management fees. Plus, instead of being too highly concentrated in just ten stocks, you can hold hundreds that are diversified across multiple industries. Sure, there will be a few “losers” in the mix, but you also own all the “winners.” That’s the beauty of it.

If you want to go broader, you can also purchase the ENTIRE U.S. Stock Market in a single fund (such as FSKAX, FZROX, SWTSX, VTSAX, etc.), which includes all publicly traded large, medium, and small companies.

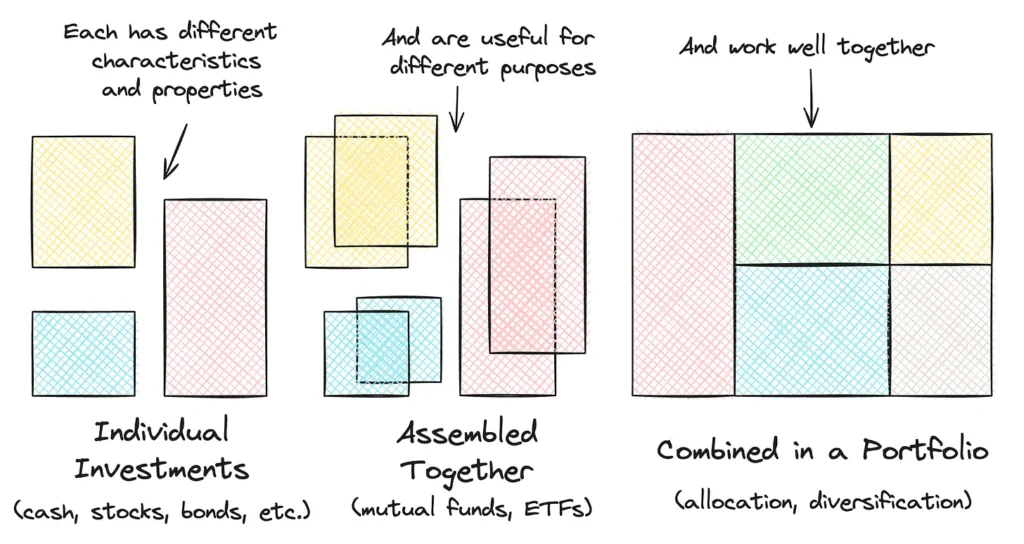

Investing uses a few basic building blocks. You take the basic building blocks (different asset types like stocks and bonds), typically that have been assembled in baskets of “funds,” and then combine the smaller baskets into a larger one (a “portfolio”) that has a specific investment goal (ex., long-term growth for retirement).

When you (or your advisor) constructs this portfolio, you’ll have to decide on an allocation strategy (how much to invest in each asset category—e.g,, 60/40 stock and bond portfolio) and diversifying within your asset categories, which is all about which baskets you use and how much money you put in each category in the baskets.

You may wonder if it’s okay for a Christian to own stock in S&P 500 companies such as Amazon, Apple, Microsoft, or Meta. Are these “Christian” companies? No. Do these companies have employees, including executives, who are sinners? Yes. Do these companies donate to causes you wouldn’t support? They likely do. Do you spend money with these companies and use products or services from any of them? You probably do. Have they been a blessing to you in some small way? Your answer is probably yes again; I know I do.

The Bible offers guidance on questions of this nature. In Romans 14, Paul tells us that there are secondary matters that believers can disagree about in grace and love. I believe that investing is one of them, meaning you are free to do so unless your conscience dictates otherwise.

If you prefer not to invest in them, there are faith-based and ethical investment funds available. Just keep in mind how difficult it is to find the near-perfect companies that also offer a reasonable return and continually screen them to ensure they remain as “near-perfect” as possible. If you’re interested in investing in some good (but not perfect) ones, I suggest Eventide Funds.

For reflection: As you progress through these articles on investing, remember that wisdom and humility are more important than the “technicals,” and investing is about more than chasing returns. It’s about growing wealth consistently through learning to build wealth wisely. Remember that investing is about more than chasing returns; it’s about steady diligence, patience, and faithful stewardship of what God has entrusted to you. Are you laying spiritual foundations as well as financial building blocks–a foundation of trust in Him, not in the markets?

Verse: “By wisdom a house is built, and by understanding it is established; through knowledge its rooms are filled with every precious and beautiful treasure” (Proverbs 24:3-4, ESV).