In the last article, I discussed the different types of financial advisors and the various settings they work in. In this article, I go into how financial advisors are compensated and what that means to you, should you choose to work with one.

In the third and final article in this series, I will discuss how to choose a financial advisor or do-it-yourself.

Some know but most don’t

According to a recent Personal Capital study, of the 60% of all Americans who are investors, only “21% of [them] know they pay fees on their investment accounts but are not sure what they pay in investment fees, while 10% of investors don’t even know if they pay any fees.”

So, according to the study, approximately a third of all investors either don’t know if they pay any fees or if they do, have no idea how much. In fact, many are paying more than they think. That’s because some fees are obfuscated by performance reporting, or withdrawn and accumulated over time. It can also be confusing because some fees go to the advisor and others go to the recommended investments’ managers.

I have been doing financial counseling and coaching for quite a few years now, mainly in the context of my local church. I have a fair amount of anecdotal data from people that I have worked with who have worked with financial advisors. Some of the general observations I can make based on that data is that many people…

- don’t know what they’re specifically invested in or why

- don’t understand what commissions, investment fees, and portfolio management fees are costing them

- don’t know (or correctly understand) how their advisor is compensated

- have been sold products that they didn’t necessarily need because they generated a high commission for their advisor

You need to know what an advisor and your investments are costing you, and then you need to assess whether they are worth that to you. Both questions can be challenging to answer.

Before I go further, I want to make some very crucial points, lest I be misunderstood:

First, I want to say that I know there are a lot of very good, well qualified, and committed financial advisors out there. Sure, some are not – but they are the exception rather than the norm. The trick is finding a good one you can trust (Matt.13:26).

Second, I want to stress that financial advisors need and deserve to be paid for their services, just like you and I do (Luke 10:7). You wouldn’t work for nothing and neither would I (unless I was volunteering my time, of course).

Third, I would say that a significant percentage of financial advisors are not as experienced, well-qualified, devoted, and successful as you might think they are (Matt.24:4). That’s because many are really just salespeople and when compared with other professions (such as attorneys and CPAs), the bar for entry is fairly low. It’s much higher for Certified Financial Planners.

Many financial advisors are trained to push specific products for their employers. There’s nothing wrong with that per se’ (that’s what salespeople do), but you need to know if that’s the case as they may be more devoted to their employer and their own sales commissions than they are to you.

Also, although the requirements to become a financial advisor are relatively low (pass a couple of exams, no experience or academic prerequisites), there are a fair number of people representing themselves as experts. However, they may not have more than one or two courses on the subject and very little professional or life experience. (Plus, their finances could be a wreck and you would never know it – the Mercedes is leased.)

Understand your total costs

Although this article is mainly about how advisors are compensated, it is essential to consider them in the broader context of total costs.

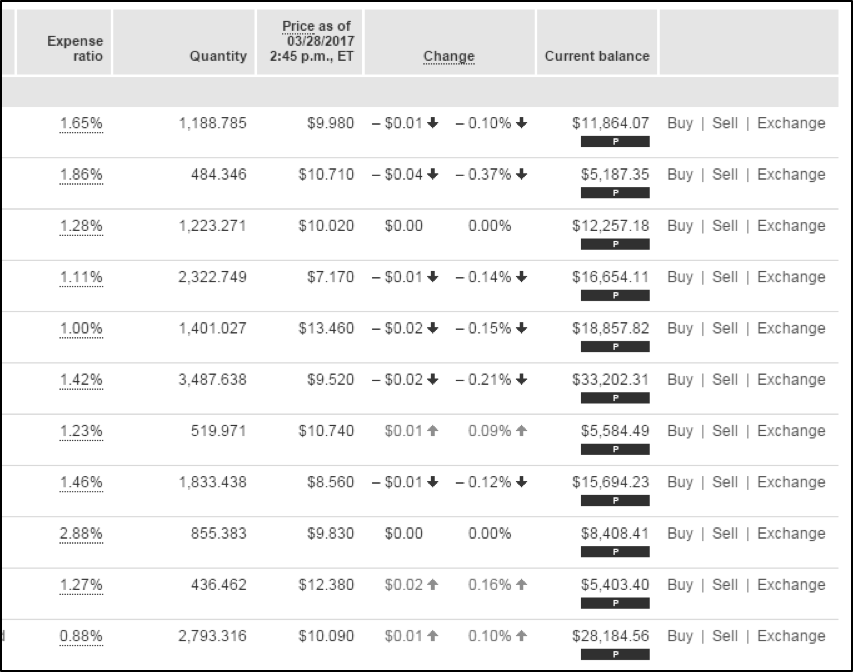

Earlier this year, a friend who was concerned about fees asked me to take a look at his IRA portfolio. He sent me this snapshot (I removed the company and mutual fund names, of course):

Look at the expense ratio column (the first column on the left). These were the expenses for the individual mutual funds in his portfolio. According to my friend, the overall average was ~1.5%. But that was in addition to the .75% that he was already paying to the investment management firm he was working with. That was 2.25% of a $160,000 portfolio, or $3,600 a year. He is a very bright guy, but he didn’t fully understand what he was being charged in total until he took a closer look. (He later wisely decided to go the do-it-yourself route and transferred his assets to a mutual fund company and created a well-diversified portfolio using low-cost index funds.)

This example is a good reminder that the total cost to you for a managed investment portfolio isn’t just the advisory fee. You also have to pay the costs associated with the investments themselves, and possibly other custodial and administrative charges.

And as it turns out, they can really add up. A prominent blogger to the professional financial planner community, Michael Kitces, wrote that “…a recent financial advisor fee study from Bob Veres reveals the true all-in cost for financial advisors averages about 1.65%.”

That’s right off the top and can be a considerable amount of money in larger portfolios, primarily if they’re conservatively invested and only growing 4 or 5 % a year. The “all-in cost” in this case includes the costs of the underlying investments (mutual funds and/or ETFs), transaction costs, and various platform fees.

The research that Kitces cited goes on to show that,

..financial advisors typically set their [assets-under-management] (AUM) fee schedules, not just at the mid-point, but up and down the scale for both smaller and larger account balances. And as Veres’ research finds, the median advisory fee up to $1M of assets under management really is 1%. However, many advisors charge more than 1% (especially on “smaller” account balances), and often substantially less for larger dollar amounts, with most advisors incrementing fees by 0.25% at a time (e.g., 1.25%, 1.00%, 0.75%, and 0.50%).

Fees, fees, and more fees

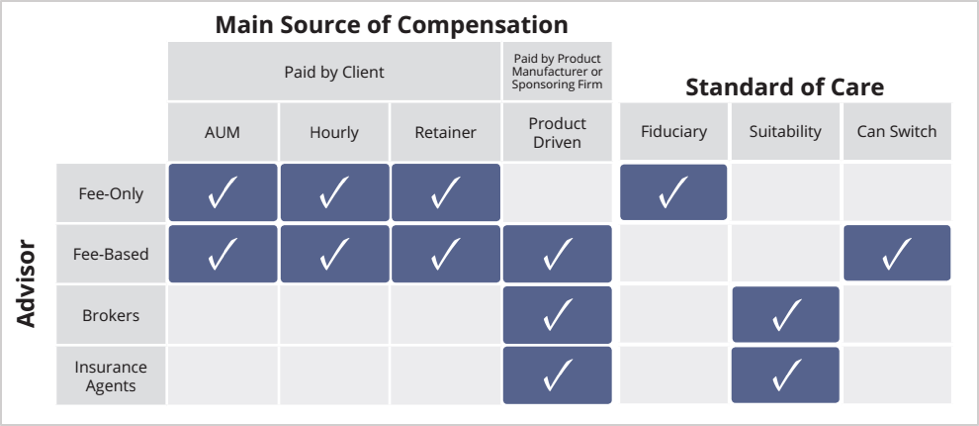

A percentage of AUM is only one of the ways advisors charge for their services. Here is an excellent chart from retirement planning expert Wade Pfau that shows the various ways that financial advisors are compensated. It aligns the compensation methods to the “standard of care” discussed in my last previous article (fiduciary or suitability or either).

As shown in the chart, there are four main ways that financial advisors are compensated:

- Assets Under Management (AUM) – fees based on a percentage of assets under management

- Hourly fees and fee-for-services – “pay as you go” for service

- Retainer – such as a flat annual fee

- Product-driven – typically via sales commissions

You can also see that there is a direct correlation between fee-only advisors and a fiduciary standard of care. Brokers and insurance agents have adhered to the suitability standard, and fee-based (hourly or fee for service) may be both.

Let’s look at each of the fee structures I listed above and how they may be beneficial or potentially detrimental to you based on potential conflicts of interest and total costs.

Asset-based fees (assets under management)

These advisors could work for any company that provides investment management services – banks, brokerages, mutual funds, small advisory firms, etc. Most robo-advisors also use this pricing model. In this scenario, the advisor is paid base on the size of assets under management (AUM). That is typically determined by a percentage of your total assets. Larger accounts usually carry smaller fees, and smaller ones carry larger fees (makes sense, right?).

As the size of your portfolio grows, the advisor will receive more fee income. If it shrinks, he will get less. In that sense, he would seem incented to help you grow your assets and minimize losses. He is motivated to make sound investment choices on your behalf.

Incidentally, this is why some advisors, especially the more successful ones, have a portfolio size minimum. Smaller portfolios just aren’t worth their time if they are only getting a .5% fee per year. That is why, as shown in the first graphic, advisors typically charge a range of fees – usually from .5% to 1.5% of AUM.

Most advisors deduct these fees directly, which can be convenient for their clients (i.e., they don’t have to write a check or deal with it in a budget.) The problem is that you may not even notice unless you carefully examine your account statements or ask them about it directly.

There are fewer potential conflicts of interest with this fee structure. However, there are some potential downsides. Advisors who charge based on a percentage of assets benefit from you having as large an account size as possible, even if that’s not the best thing for you. For example, when you would be better served by saving less and using the money elsewhere or by liquidating some assets and paying down debt, or when you need a larger cash cushion for emergencies. Also, if you have a smaller portfolio, you may not get the same amount of attention as clients with larger ones. (1% of 100,000 is $1,000/yr whereas .5% of $500,000 is $2,500!)

You need to be aware that there are some variations of this model. There are “fee-only” advisors and “fee-based” advisors. Fee-only advisors who only charge based on AUM are more likely to recommend lower cost investments for your account, minimizing the overall expenses you pay to help grow your assets faster. “Fee-based” advisors may be able to collect sales commissions in addition to the percentage fee charged on assets.

Hourly fees and fee-for-service

In this case, you pay the advisor (or planner) by the hour or for a particular service. For example, you may pay them to perform a risk analysis on your current portfolio. Or you could ask them to run a retirement planning model for you to tell you how much you need to retire by a particular time.

Since the hourly rate is not tied to any other measure or the purchase of any specific product, you can be reasonably confident that you are getting objective advice. That can be especially good if you are willing and able to implement the recommendations on your own (thus eliminating ongoing fees).

As with attorneys and accountants, the hourly rates or fees-for-service that advisors charge can vary widely from one to another. A highly experienced advisor, or someone with in-depth knowledge in a specialty area, such as retirement planning, will charge more. Less experienced advisors will charge less.

One thing to keep in mind, however, is that any advisor who is a good businessperson is looking for new business. If you come in as an hourly fee customer, he may try to convince you to sign up for other services. Hourly or fee-for-service advisors may have an incentive to “over plan,” that is, to sell you services that you don’t really need.

Sales commissions

Typically, financial advisors who work for brokerages and insurance companies are paid by commission. The may also receive a small salary, but the bulk of their pay comes from commissions on product sales.

In addition to their commissions, if they meet their sales targets for the year, they may get a bonus. If they don’t, they make less and could even lose their job. If they exceed it, they can earn additional bonus pay.

As you can see, commission sales can be a tough business – it can be challenging for the salesperson, and it can also have negative impacts on you. That’s because the advisor’s recommendations can be influenced by the way they are compensated. The bigger the commission, the more likely an advisor may be to push you to purchase a particular investment product. Unfortunately, greed can become a driving factor (Ecc.5:10).

Commissions are paid in a variety of ways. Many people believe that all of their money goes into whatever investment they purchase and then the investment company pays the salesperson out of their pocket. Wrong! In most cases, the commissions come right off the top, and your investment is immediately reduced accordingly. Rarely does the investment company pay the advisor directly out of their own pocket.

One example is a front-end charge (called a sales load) on a mutual fund. Another is the commission for the sale of an annuity. If you invest $10,000 in a mutual fund with a 5% load, you will pay $500. If you invest $100,000 in an annuity with a 5% sales charge, you will pay $5,000. That is a big deal, especially if you consider what that money would be worth 20 years down the road if it grew modestly at 5% a year.

Remember, many other fees may apply when you purchase an annuity, depending on the features and benefits you choose: guaranteed income fees, guaranteed lifetime withdrawal fees, fees on the underlying investments, etc. Some of these features may be desirable to you but be sure you understand what they cost.

There are also charges that occur on the “back-end” of some transactions. These are usually associated with products that have a surrender or cancellation charge, and in return, the investment company pays the salesperson directly instead of an upfront charge to you. But if you bail early, you will pay directly, and maybe dearly. Early termination charges are common with many life insurance and annuity products.

Finally, there is what is called “trailing fees” or “residuals.” In this case, the salesperson receives an ongoing fee that is taken directly from your investment year after year. One of the significant problems with this is that you may not even notice since they are debited automatically and tend to be smaller amounts (less than .5%).

Retainer

The most common form of this fee structure is the “flat annual fee.” This type of charge is just a fixed amount that you pay regardless of portfolio size, transactions, etc. The problem that I see with this approach is that it may give advisors who charge flat fees have an incentive to do just the minimum amount of work possible to keep you around.

Which fee structure is best?

As we have seen, there are positives and negatives with each compensation method. I have concerns with all of them.

I do like the fiduciary aspects usually associated with advisors who charge asset-based fees. What I don’t like is that you pay the fee on an ongoing basis, regardless of the level of service you receive year-by-year. That makes the “fee-for-service” a little more attractive as its more of a pay-as-you-go model.

Both of those methods may have fewer potential conflicts of interest than those that can be involved with commission-paid advisors. But, with a commission-only approach, you only pay when your advisor/broker sells you something or purchases it on your behalf. That could reduce your overall costs, especially if those transactions are infrequent (i.e., there isn’t a lot of “churning” going on in your account that you don’t know about.)

And be careful about advisors who tell you that their fees are being paid by the investments themselves. The pitch is that they “earn their keep” by buying and selling and reallocating your assets so that you earn more than “the market” and in the process, they “get paid.” Well, they do, but that money has to come from somewhere and its usually from commissions.

So, the “which is best” question is hard to answer because of the nuances involved. For example, an advisor who charges based on AUM will tell you that a fee of .75% is a great value because he or she will enhance your returns by more than that, so they are worth every penny – and maybe they aren’t. Or, he/she may claim that the up-front sales charge of 5% is well worth it because the investment is a top performer. If you are purchasing an annuity, you may want add-on features that you believe are well worth the additional expense.

What if you could find an advisor who is just as good but only charges .25% of AUM? (That happens to be the range that most robo-advisors are in.) Wouldn’t that be the way to go? Perhaps, as long as you genuinely believe that the value you receive is higher than the cost.

How can you know?

In the next article, I will discuss choosing a financial advisor. But no matter who you select, be sure to get a full explanation of how they are compensated before you hire them. Ask good questions and seek honest, direct answers. If the advisor is evasive or implies that fees don’t matter, leave and look elsewhere.

If they are paid based on AUM or fee-for-service, make sure you know what the percentages or rates are and how and when you pay them. If they are commission-based, make sure you know how much they will receive if you purchase the investments or insurance products they recommend and how it will be deducted from your account.

Finally, make sure you understand the costs associated with the investments in your portfolio, which would be in addition to whatever you are paying the advisor. That can be a little tricky because they are usually deducted by the investment management company before the earnings are reported.

If you do these things, you can enter into any advisory relationship as a well-informed investor, and that will help you make the best decisions possible for your retirement stewardship.