Suppose you’ve decided to keep a portion of your portfolio in bonds, perhaps with a higher allocation percentage than stocks. In that case, you have another decision: Should you invest in individual bonds or a bond fund?

With interest rates at higher levels than they’ve been in many years, some folks (including yours truly) wonder if they should try to “lock in” these higher yields by purchasing individual bonds and holding them to maturity. Or is it better to stick with bond funds?

Why the sudden interest in individual bonds?

We first need to review how bonds work.

Bonds pay interest based on their “coupon rate.” The coupon is the interest rate paid by the bond. The rate is set when the bond is issued and doesn’t change. For example, a $10,000 bond with a coupon rate of 3% will pay coupons of $300 per year for the life of the bond—a yield of 3% on the original face value of the bond known as its “par value” (in this case, $10,000).

A bond’s coupon rate is different than its yield. Yield is the actual return from a bond (or bond fund). A bond’s yield is the coupon rate divided by its current market price.

For example, the bond initially issued at a par value of $10,000 that is now priced by the market at $9,500 with a coupon of 3% has a yield of (.03 / 9500 )= 3.16%, which is .16% higher than the original yield of 3%.

Thus, if interest rates rise (or fall), it will affect a bond’s yield but not the coupon.

A bond’s price and its yield are inversely related. When interest rates rise, and bond prices fall, the yield increases. That’s because the coupon rate (which is unchanged) is a larger percentage relative to the bond’s current price.

If rates fall and bond prices rise, the yield will decrease—the coupon rate is a smaller percentage of the higher bond price.

However, none of this matters if you buy a bond paying a coupon of 3% and hold that bond to maturity. The market price may fluctuate due to interest rate changes, but you’ll get the promised coupon payments and the return of the bond’s par value.

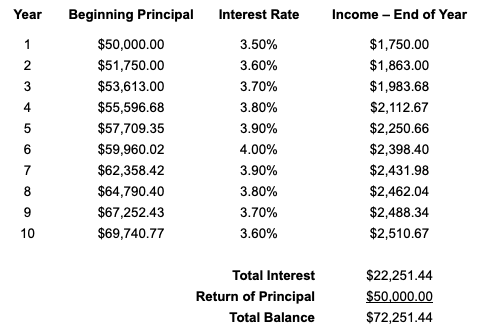

This simple spreadsheet illustrates how this would work if you invested $50,000 in a one-year bond and then let it mature, and then rolled it over into another one-year bond, and repeated that process for ten years at rising and then falling interest rates:

As you can see, you’d never lose money on your original principal amount ($50,000) and would receive total interest (coupon payments) of $22,251. So, at the end of ten years, you’d have $72,251 ($22,251 + 50,000 = $72,251).

Since interest rates are currently higher than they’ve been for a long time, the promises of both fixed coupon payments (which retirees may like as income to spend) and the total return of principal by holding bonds to maturity (regardless of what direction rates go) are more attractive now.

Holding individual bonds

Individual bonds (or an individual bond “ladder,” which is built holding individual bonds with different maturities) differ in many ways from a bond fund. Still, both are good investing tools, depending on your situation. As we’ll see, individual bonds will be better for some, and a fund will do just fine for others.

When interest rates rise, the value of all bonds declines—both individual bonds and those held in funds. So how would having an individual bond be better than a bond fund?

If you buy individual bonds and hold them to maturity (which may not be possible if they are “callable“), you’ll get your original investment back—its “par value.” But you’ll get back non-inflation-adjusted dollars worth less than when you bought the bonds (unless deflation occurred during that time).

For example, if you own a $10,000 treasury bond with a 5-year term and a coupon of 2%, you’ll receive $100 every six months ($10,000 x .02) ÷ 2 = $100. Assuming you bought it when it was first issued, at the end of 5 years, you’ll also receive your entire $10,000 back.

Your total earnings for the five years will be $1,000, or 10% ($200/year x 5 years = $1,000, which is 10% of $10,000). (Note: This is different from a bond’s “yield to maturity,” a more complex calculation that’s a discussion for another time.)

Let’s say that five-year treasury bonds are currently yielding 4%. The market price of your 2% bond will go down, but you’ll still receive the 2% coupon, plus you get the money you paid for the bond back at par value if you hold it to maturity.

But what if you sell your 2% bond and buy a new issue paying 4%? Our intuition tells us we should be better off in the long run but are we?

No, not really, and here’s why: When you sell the 2% bond, you’ll take a loss—you’ll get less than for the bond than you paid for it. If you sold 2.5 years into the five-year term, you’d get about $9,500 instead of the $10,000 you invested initially. That’s a loss of $500 or 5%.

However, you’ll earn an additional $200 a year in interest (based on the higher 4% interest rate) for the next 2.5 years, and your interest payments will total $1,000, which equates to the $500 loss of principal plus the $500 you would have received if you’d kept the original bond.

To sum up: you’re no better off than you were in the first place.

That said, you still have another 2.5 years to hold the new bond, and you’ll get the higher interest payments for that period. But, if rates for 5-year bonds are still at 4%, you could buy a new five-year bond and lock in the new 4% rate for that term.

This shows that individual bonds are best when held to maturity, and selling before maturity for newer, higher-yielding bonds doesn’t significantly improve your situation. But what about bond funds—don’t they do just that?

Bond funds—same, but different

Now that we understand how individual bonds work, we can compare them to bond funds. And the answer to the question above is that bond funds do both—they buy and hold and buy and sell to optimize returns.

Bond funds hold individual bonds (securities) that are repriced daily based on current interest rates and, to some extent, where investors expect rates to be in the future.

I own an iShares bond ETF: USIG (iShares Broad USD Investment Grade Corporate Bond ETF). Its current yield is about 3.5%, and it holds about 9,400 bonds.

As you know, all of these types of funds have lost money over the last year due to rising interest rates. When rates rise, the value of all bonds goes down, whether you hold them individually or in a bond fund.

USIG has an effective duration of about seven years; it’s considered an intermediate-term fund with moderate interest rate risk. That’s one of the reasons its market value was down a little over 15% for 2022.

I also own a short-term bond index fund, a total bond index fund, and a TIPS fund. I have a relatively conservative bond allocation, which seems right to me as a 70-year-old.

Bond funds like USIG operate indefinitely, paying interest dividends that fluctuate as rates rise and fall. Bond funds are desirable to retirees looking for reliable income.

To maintain the overall profile of the fund, it will periodically sell funds that fall short of its maturity (or risk) target and purchase new bonds.

In a time of rising rates, a fund may sell bonds at a lower price than they bought them and buy new ones at higher prices that are paying higher interest.

It will also keep many to their full maturity and replace them with new bonds with higher coupons.

These activities will, over time, effectively “refresh” the bond fund’s holdings to higher-yielding securities, resulting in larger interest payouts to their shareholders. However, the upticks tend to come slowly.

Also, if interest rates go down (which they inevitably do), the market price of those bonds will go up, increasing the value of a fund’s holdings.

Which is better?

Now we know the critical difference between holding individual bonds and bond funds. We’re talking about two distinctly different uses of bonds in retirement portfolios beyond just diversification for stocks.

Investors who purchase and hold individual bonds to maturity will receive a predetermined yield and total return of principal (if the bond isn’t called or defaulted). But bond fund yields and prices fluctuate, so selling shares before maturity can result in capital gains or losses.

Thus, in a time of rising rates, holding individual bonds to maturity will usually perform better than bond funds held for similar periods. That suggests that holding individual bonds instead of funds may be better for those who need a specific sum of money at a particular time in the future and can’t afford losses due to market repricing.

That makes individual bonds an ideal way to fund a known future spending liability, such as a car or house purchase or a year of college or retirement income.

The investor most interested in income and does not need to sell bond fund shares to help fund their retirement may be comfortable holding bond funds over the long term.

What about retirees?

If you’re using bonds mainly to diversify your portfolio and provide income in retirement, then funds may be the way to go. That’s my main objective, but I’m also attracted to the idea of ‘locking in’ today’s higher yields by purchasing individual bonds, especially TIPS, for inflation protection.

I’ve made my current fund selections and allocations based on duration and quality. Generally, in keeping with my bucket strategy, I’ve matched the fund’s duration to an anticipated holding period, but not precisely since I’m mainly aiming for interest income, not to sell appreciated bond fund shares unless I have to.

Yes, my intermediate-term bond funds (USIG and BND) have lost money this year, but since their durations are six years or more, and I don’t plan to sell shares of those funds for retirement income during that period, I’m less concerned.

I have short-term needs covered in my “cash bucket,” and as I mentioned previously, I also have a short-term bond fund (BSV) and a short-term TIPS fund (STIP). If I need cash in the near term, which I do, it will come from there in accordance with my bucket strategy.

Perhaps you’re in the “need a specific sum to spend in the future” camp and are considering using individual bonds. In that case, it will come down to your tolerance for complexity and the desire and ability to construct and manage a portfolio of laddered individual bonds (or pay someone to do it for you).

I’m still intrigued by the potential of individual bonds and a bond ladder, in particular, to lock in today’s high yields while protecting my principal if held to maturity. So, in the next article, I’ll discuss bond ladders in greater detail (and the type of ladder many professionals recommend for retirees).