We’ve discussed investment risk, the concepts of your risk tolerance, and risk capacity. We’ve also looked at the fundamental building blocks of an investment portfolio. Now it’s time to talk about your "asset allocation,” and why it’s so important.

Asset allocation involves deciding which investment “buckets” to allocate your assets to, and in what amounts as a percentage of your total investment; for example, 80% in stocks, 15% in bonds, and 5% in cash.

I want to say up front that I don’t know what the “right” asset allocation is for you. However, I will try to give you some guidance to make a wise and informed decision. And I certainly don’t know which allocation strategy will make you the most money with the least risk over the next several decades. Anyone who claims to have that superpower is trying to fool you. I’m not smart enough or clairvoyant enough to give you a specific answer since I don’t know what the future holds–only God does (Isaiah 46:10).

Based on decades of historical performance data, I believe there is a high probability (more than 50%) that stocks will likely outperform most other investments over long periods. For that reason, I think all investors should allocate some of their assets to stocks. But my level of certainty isn’t high–it’s 51%, so there’s a 49% chance I’m wrong. I maintained a 60% stocks/40% bonds allocation for most of my working life, but looking back, I realize I was too conservative. Stocks outperformed bonds by a wide margin.[1] But I was able to sleep at night.

The primary goal is to have a portfolio mix that allows you to sleep at night. In other words, if you’re a 20-something, even if your risk capacity is very high and you could invest 100% in stocks, your risk tolerance may not allow you to. You may need to mix in some less-risky assets, like bonds. That may sound easy enough, but there’s no magical allocation that will protect you against the risks in investing.

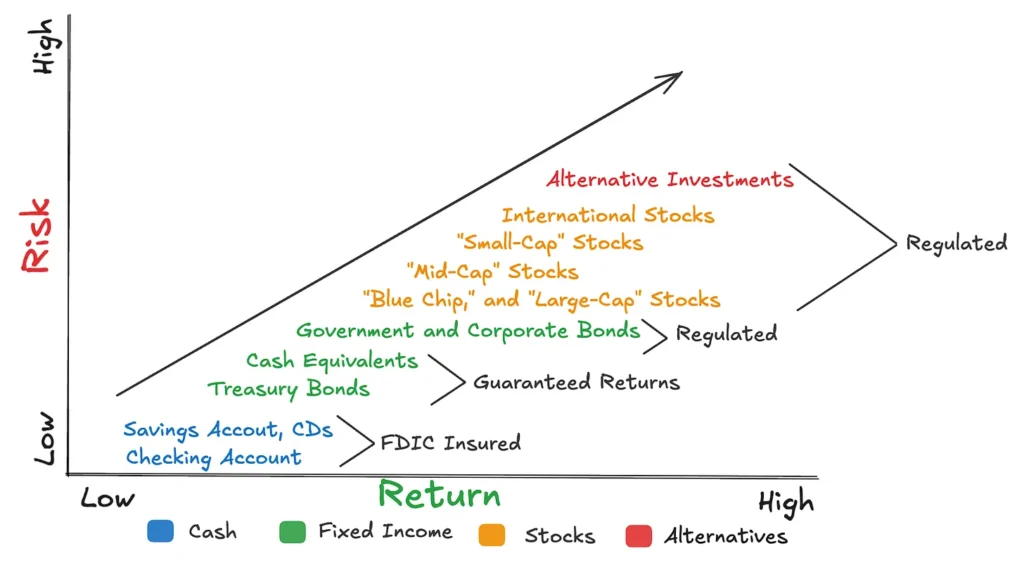

You have to decide where you think the most significant risks are, and your investment decisions should be based on limiting exposure to them. However, I think you can see the challenge: how do you determine where the most significant risks are? The chart below shows the risk versus return of the various investment building blocks we discussed in the previous article:

As you can see, cash and fixed income are relatively low risk, blue chip and large-cap Stocks are moderately risky, and smaller stocks, international stocks, and alternative investments are the most risky. The returns from cash and fixed-income investments are usually lower over the long term than those from stocks and alternatives.

I mentioned earlier that investing always involves some level of risk. Even keeping your money all in cash carries the risk of devaluation due to inflation. So, the idea is to allocate your investments in a way that takes a reasonable amount of risk while enabling you to “stay the course”; i.e., not bail out when the going gets tough, as it surely will.

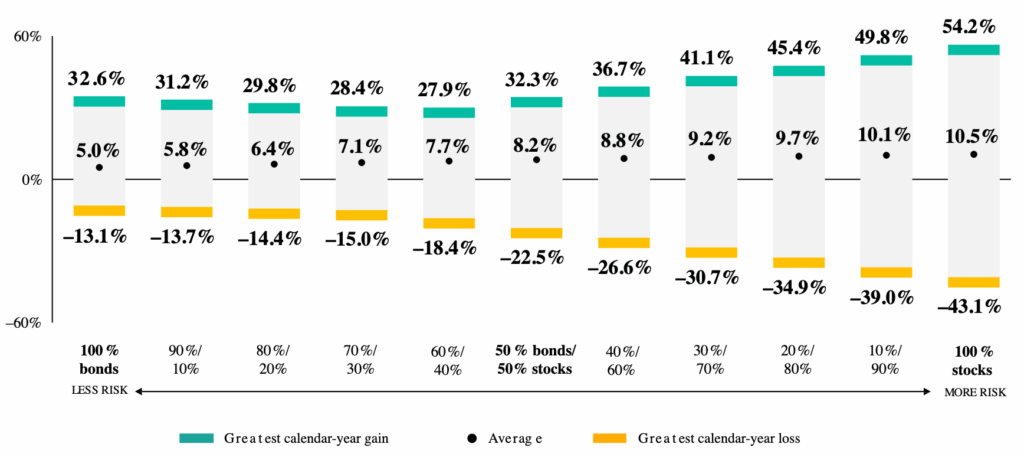

I will show you how asset allocation can (usually) mitigate portfolio losses resulting from significant stock market corrections or crashes. You’re probably thinking, “Oh, great, more math.” I promise this is a simple illustration—with a little bit of math—that shows how asset allocation can be your friend in such situations.

Consider this: what if stocks fall by 50 percent (the worst-case scenario in the most severe circumstances short of a global economic Armageddon)? How much of a total drop in your portfolio could you handle without panicking and selling everything, effectively locking in losses?

Let’s say you’re 30 years old and think you could handle a 30 percent drop in your portfolio’s total value. (Which, by the way, would require a ~43% increase to recover; I’ll spare you the math on that one.) Subtract twice the maximum reduction of 30% from 100% to come up with your bond allocation percentage: (2 x 30% = 60% bond allocation). Your stock allocation percentage will then be 100% minus the bond percentage: (100% – 60% = 40% stock allocation). The result is a personal risk-based allocation of 40% stocks and 60% bonds.

Some (perhaps most) investment professionals would say that a long-term 40/60 stock/bond portfolio is too conservative for a 30-year-old with a high risk capacity. And they’re probably right. But that’s not the point.

Now, let's see what would happen to this portfolio if the stock market were to drop by 50%. Wow, that would be crazy! You would lose 50% of the 40% allocated to stocks, resulting in a 20% loss. Although this isn’t always the case, let's also assume your bond component increases by 10% during this event (10% of 60% equals a 6% increase). If you add your remaining 20% in stocks to your 66% in bonds, your portfolio will be down "only" 14%. However, if bonds stay flat, you’ll lose 20%, less than you initially said you could tolerate.

A note of caution: sometimes, both stocks and bonds decline simultaneously (the COVID-19 pandemic crash in March 2020 is a notable example). But they seldom decline the same amount. And, bonds may go up when stocks go down. What happens with bonds depends on the underlying cause of the stock market decline and the types of bonds in your portfolio.

Let’s consider another scenario. What if the stock market is up 25%? If bonds are essentially flat, your portfolio will be up only 10% (=25% x 40%). This is a time you’ll wish you had invested more in stocks. I think you see the dilemma that younger, long-term investors face as they try to balance risk and reward.

But wise investors don’t just chase returns; they balance potential rewards with their ability to endure losses. You might be tempted to load up on stocks for higher gains, but ask yourself: Is it worth the sleepless nights if the market crashes? Ironically, playing it too safe can be just as risky. If you put everything in low-yield CDs, Treasuries, or annuities, you might preserve your principal, but risk not reaching your savings goals. That’s called shortfall risk.

The goal isn’t to avoid all risk—it’s to take the right amount of risk for your goals and personality, your temperament. And that’s a moving target as your life changes. A common way to come up with an age-appropriate stock/bond allocation is to subtract your age from 100 to get your stock allocation. So if you’re 30, you’d have 70% in stocks.

But this has been modified recently to “Subtract your age from 110.” So, at age 30, and planning to work until 70 (=110 – 30) = 80% stocks. These are just starting points. You’ll need to tweak your allocation based on real-life goals, market conditions, and your emotional comfort level.

You may also want to adjust your asset allocation over time. Ordinarily, you would reduce the percentage of your assets allocated to higher-risk investments, such as stocks. Here’s a very simplistic way to approach this that will give you an idea of what your allocation might look like and how it will evolve as you age:

- Low risk tolerance = “age in bonds”

- Medium risk tolerance = “age minus 10 in bonds”

- High risk tolerance = “age minus 20 in bonds”

Using this approach, a 35-year-old with a medium risk tolerance would hold 25% in bonds (=35 – 10), resulting in a 75/25 portfolio. (Remember, asset allocation is written as a ratio of stocks to bonds, such as 75/25, which means 75% stocks and 25% bonds.) However, a 65-year-old with a low risk tolerance would hold 65% in bonds (=65 – 0), a 35/65 portfolio.

Vanguard offers a helpful chart that displays historical returns and risk metrics for various asset allocation models, which can help inform your decision-making process. Once again, use this as an informational tool in your arsenal, but also remember that the same performance seen on that page may not occur in the future. Many economists and investment professionals believe that returns will be significantly lower over the next couple of decades.

The reason it’s so important to find an allocation that you feel comfortable with is so that you’ll stick with it. When you invest consistently over 20, 30, or 40 years, you buy shares at both high and low prices– this is called “dollar cost averaging.” The low years, when things feel bad, are opportunities to buy stocks “on sale.” When you’re young, your biggest asset isn’t just money, it’s time. So, find an allocation you’re comfortable with, and when the market drops 20% in a year, don’t panic. Keep investing. Stick to your plan. If possible, increase your savings. Remember: time in the market beats timing the market, especially for young investors.

Okay, you’ve come up with an 80% stock/20% bond asset allocation, so what's next? How do you build that portfolio? We’ll tackle that in the following article, but I’ll tell you up front: it’s MUCH SIMPLER than you might expect. Just keep the investment building blocks in mind that we discussed earlier.

For reflection: A wise steward builds their portfolio thoughtfully, balancing risk and reward in light of their goals and guidance from God’s Word and prayer. Reflect on whether your current allocation shows wisdom and reflects an understanding of your own heart, your future needs, and your calling to steward God’s resources well. Pray for guidance to make wise choices so that you can stand firm in changing markets, when things can get tough.

Verse: “So teach us to number our days that we may get a heart of wisdom” (Psalm 90:12, ESV).

Notes:

[1] https://www.investopedia.com/articles/basics/08/stocks-bonds-performance.asp