As retirees, we rarely discuss time unless it’s to inquire about the current hour. When was the last time you were at a dinner party and someone asked you, ”Hey, <insert your name here>, how much time do you think you have left?” Polite people don’t ask such things. However, as we get older, the subject of time becomes a more prominent topic on our minds.

We chronologically perceive time as we age. We mark retirement milestones with birthdays and anniversaries, and then things like our Social Security and Medicare eligibility ages, as well as the IRS’s requirement to begin taking required minimum distributions from our IRAs at age 73.

History itself is marked by time and could not be understood without it since time can be simply understood as a succession of past events. But the most significant marker in all of history is the incarnation. Christopher Watkins, in his book Biblical Critical Theory, describes it this way:

“It (the incarnation) acts as the pinpoint focus to which all time before it is drawn, and from which all time after it radiates out. . . As we move forward in time past the incarnation, we will witness not a further constriction but an explosion in the scope of the narrative as, by the end of the Bible, God’s plans are again seen to encompass the whole universe.” (p. 349)

Watkins elaborates,

“So there we have it: it all ends. Only, it does not all end. Not a bit of it. The end of the Bible does not have the feel of a closing down sale but of a grand opening gala. Permanence, certainly, but not finality. Christ is alive for ever and ever.” (p. 549)

What is time?

Time and space are finite realities but abstract concepts, making them easy to experience but difficult to define. As St. Augustine wrote in Confessions,

“What is time? If no one asks me, I know. If I wish to explain it to one who asketh, I know not.”

Although time is an abstract concept, it has always been a subject of great interest for Christians and atheists alike. While we may differ in our beliefs regarding its origins and purpose, we all share the experience of time and space.

Scientists (astrophysicists and cosmologists in particular) are very interested in the subject. Galileo was one of the first scientists to study time and relativity, but Albert Einstein is perhaps the most famous due to the publication of his “Theories of Relativity,” which postulated that space, time, and gravity are interconnected and that time is not absolute.

In other words, despite our common perception that a second is always a second everywhere in the universe, the rate at which time flows depends on where you are and how fast you travel. You may have heard his famous claim that time slows down as you approach the speed of light.

I’ve always been interested in astronomy and cosmology (it was my college major for a while after I ditched oceanography, but then I realized it would be even harder), so I was curious about some of the contemporary thinking on this subject. I came across a scientist named Dr. Sean M. Carroll.

Sean Carroll, a well-known modern-day atheist, philosopher, and physicist, explores the concept of time in his book Eternity to Here: The Quest for the Ultimate Theory of Time. When asked, “What is time?” by a wired.com writer, he replied,

“That’s a huge question that has lots of different aspects to it. Many of them go back to Einstein and spacetime and how we measure time using clocks. But the particular aspect of time that I’m interested in is the arrow of time: the fact that the past is different from the future. We remember the past, but we don’t remember the future. There are irreversible processes. There are things that happen like you turn an egg into an omelet, but you can’t turn an omelet into an egg.”

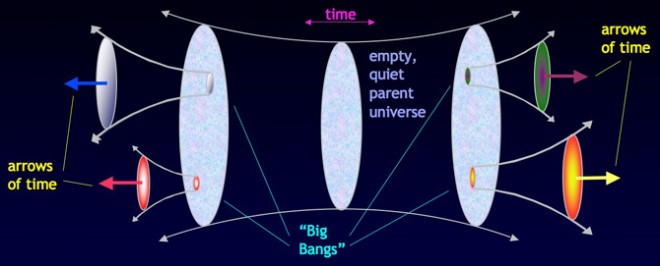

Carroll’s theories revolve around “arrows of time” and the notion that entropy (a state of disorder, randomness, or uncertainty) permeates the universe and progresses over time (citing the second law of thermodynamics). Carroll says that entropy and the arrows of time move together, and things get messier and more chaotic as entropy increases. He suggests that the universe originated from a big bang but with “exquisitely low entropy,” but will eventually decline towards nothingness as entropy acts on it.

As shown in the graphic below, the source of these “time arrows” in our universe is a “parent universe” that’s part of a larger “multiverse.” In the multiverse, there is a static universe in the middle, and from there, smaller universes (like ours) pop off and travel in different directions or arrows of time. So, theoretically, in the universe at the center, there is no time. Theoretically.

I can understand why the concept of a multiverse and the idea of a static universe at its center from which smaller universes branch off and travel in different directions because of a bunch of big “bangettes” would be intriguing hypotheses to atheistic physicists and cosmologists. Absent belief in a Creator God, Carroll presents a somewhat rational (although I’m wondering where the parent universe came from) but ultimately unprovable theory on the origin and nature of time. (Some might say he’s been watching too many Marvel “Avengers” movies. The Guardians of the Galaxy is my favorite by far.)

I’m going to go a little farther afield here and say that, from a theological standpoint, it’s interesting to consider whether the arrows of spacetime Carroll described in the multiverse theory could be compared to the spacetime continuum that was set in motion by the Creator.

The notion of God as the static universe in the middle of the multiverse, directing the arrows of spacetime, is a fun analogy that connects Carroll’s scientific concept with Christian beliefs. The idea that entropy, as described by Carroll, could be a consequence of the fallenness of God’s original perfect creation is also an intriguing perspective.

Christians have a very different view of time. We regard it as a story authored by God that begins not at creation but with the existence and fellowship of the Trinity in eternity past. After the Triune God creates the world, which means everything everywhere; what we understand as spacetime is set into motion. But, as theologian Herman Bavinck so eloquently tells us, it’s for a grand and glorious purpose:

“The church confesses . . . [that] God is above the world, distinct from it in essence, and yet with his whole being in it at the present time and nowhere, in no point of space and for no moment of time separated from it. He is both distant and near—highly exalted and at the same time deeply ingrained in all his creatures. He is our Creator, who, distinct from his being, brought us forth by his will. He is our Redeemer, who saves us, not by our works but by the riches of his grace. He is our Sanctifier, who dwells in us as in his temple. As a triune God, he is a God above and for and in us.” (The Wonderful Works of God, p. 106)

This biblically orthodox view of time is based on the creator-creature paradigm, which asserts that creation, including space and time, is temporal and entirely dependent on God, the sole, unique, and absolute cause of all that exists.

As we live our lives, we recognize that time is moving, sometimes at an agonizingly slow pace, towards a glorious culmination of all things at Christ’s return: the resurrection of the dead, the final judgment, and the new heavens and earth where God’s people will dwell eternally with Him.

Bavinck explains this biblical view of time:

“Scripture tells us that the world is finite… that the world has had a beginning and that it was created together with time… nevertheless Scripture also teaches that it has no end. It will, of course, have an end in its present form, for the form of the world passes away, but not in its substance and essence. The world exists in time and continues to exist in it, even though in another dispensation an entirely different standard of measurement is used than is employed now on this earth.” (The Wonderful Works of God, p. 157).

In other words, the world as we know it was created along with time by God. And time as we know it will cease to exist, but it will be replaced, not with nothing, but with something else when God creates the new heaven and new earth. Scripture doesn’t tell us what the new standard of measurement will be; we can only think of it as eternity.

Implications

The prevailing cultural view of time and human life, in general, is that it’s linear and heading toward a catastrophic end, a “wall,” which is a nihilistic, annihilistic view of it. That results in a focus on the here and now with little or no concept of the eternal. It emphasizes living life to its fullest in the present because that’s all there is. However, as Christians, we have a unique perspective on time and its significance. We understand that our lives extend beyond a temporal, earthly existence and have eternal implications.

A Christian view of time acknowledges that although we live in spacetime here on earth, we have been ushered into another kingdom without end, having been brought from spiritual death to life in Christ by grace. As God’s redeemed people, we’re called to reflect the amazing grace we have received in how we live our lives, including during retirement. The gift of time in retirement should be cherished, and it provides an opportunity to extend God’s grace to those around us—our neighbors, co-workers, families, and the world.

Still, we all understand the uncertainty of our time on this earth. We recognize the brevity of our earthly existence (Ps. 39:4). The Bible describes our lives as fleeting (James 4:14), emphasizing the importance of making the most of the time we have been given (Ps. 90:12, Eph. 5:16). As stewards of God’s mysteries and as citizens of both this world and the world to come (1 Cor. 4:1), we’re called to seek the things that are above and to live with a future-oriented mindset.

Christians are sometimes accused of being too “heavenly minded.” But C.S. Lewis in Mere Christianity suggests we have the opposite problem:

If you read history you will find that the Christians who did most for the present world were precisely those who thought most of the next. It is since Christians have largely ceased to think of the other world that they have become so ineffective in this.“

The Apostle Paul calls us to “seek the things which are above” because our “citizenship is in heaven.” We are citizens of this world, but we are also citizens of the world to come. This is both a present and future reality and brings with it a great mystery (Col. 1:20, 3:1, 2 Cor 5:20, Phil 3:20).

This concept of living in two worlds, the temporal and the eternal, is a very counter-cultural perspective on time. Our faith assures us that our earthly time is not the end but a part of a larger narrative that extends into eternity. This understanding should shape our retirement outlook and how we approach our remaining days.

A biblical perspective on time encourages us to live with a sense of meaning and purpose, recognizing the eternal significance of our actions and the value of cherishing the time we have been given, regardless of its duration. We can also live with assurance, hope, and peace, knowing that God will ultimately bring all things to their fulfillment according to His plan (Col. 1:5).

We’re called to navigate the mystery of time with faith, trusting in God’s sovereignty and His redemptive purposes. Our lives, actions, and decisions are significant in the temporal realm and eternity. We are told to live as faithful stewards of our time, reflecting God’s grace and love for others.

In his book Surprised by Hope, N.T. Wright put it this way:

“The point of the resurrection … is that the present bodily life is not valueless just because it will die … What you do with your body in the present matters because God has a great future in store for it. What you do in the present—by painting, preaching, singing, sewing, praying, teaching, building hospitals, digging wells, campaigning for justice, writing poems, caring for the needy, loving your neighbor as yourself—will last into God’s future.”

Jeff Haanen, in his book, An Uncommon Guide to Retirement, recounts one of the final climatic scenes in Dicken’s classic A Christmas Carol (I really like the George C. Scott 1984 version):

“As he begged the Phantom for another chance, the specter’s hood and dress become a bedpost. Scrooge realized he had been sleeping. He exclaims, “I will live in the Past, the Present, and the Future. The Spirits of all Three shall strive within me. Oh, Jacob Marley! Heaven, and the Christmas Time be praised for this!” And Dickens comments, “Best and happiest of all, the time before him was his own, to make amends in!” This, I believe, closely approximates a Christian view of time. We were dead, but are now alive. All was lost, but—by grace—we’ve been given another chance. The time we’ve been given in retirement is an opportunity to reflect such amazing grace to our neighbors, our co-workers, our families, and to the world. The days in retirement may seem long, but the years are short. Let’s all live like the redeemed Scrooge, overjoyed by the gift of time.” (pp. 110-111).

Scrooge pledged to live in the past, the present, and the future. We may not often think of it this way, but we also live in all three. We live in God’s past works of grace that brought us to salvation, and we are now time travelers between this earth and the new heavens and new earth yet to come. We are part of a new kingdom that came in the past and is coming forward into the present because of the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus Christ, and will come to its total fruition in the future in God’s good time.

We all long for that day, ”But do not overlook this one fact, beloved, that with the Lord one day is as a thousand years, and a thousand years as one day” (2 Pet. 3:8).