This article is part of the Retirement Financial Life Equation (RFLE) series. It was initially published on October 18, 2017, and updated in January 2026.

The question “Are advisory fees worth it?” doesn’t have a simple answer. It depends on what you’re getting, when you’re getting it, and what mistakes the advisor helps you avoid.

During the March 2020 crash, when my portfolio declined 30% in three weeks, I observed friends with advisors remain calm while some highly intelligent DIY investors panicked and sold at the bottom, locking in substantial losses. Those advisors earned their annual fee many times over in that single month by simply keeping their clients from doing something catastrophically stupid.

Conversely, I’ve also watched friends pay 1.5-2% in combined fees (advisor plus investment expenses) year after year, even during bull markets, when their advisor did little more than send quarterly statements and rebalance occasionally. In those years, the fees were harder to justify.

What I’ve learned is that advisory fees are worth paying when they provide genuine value—behavioral coaching during crises, sophisticated tax planning, complex retirement income strategies, estate coordination—but they’re a waste of money when they’re simply buying you a portfolio of index funds you could have assembled yourself in an afternoon.

The good news is that the fee landscape has improved dramatically since 2017. Fee compression has been real and significant. Transparency has increased. New models have emerged that better align costs with the value delivered. This update reflects those changes while maintaining the core principles about understanding what you’re paying and why.

In the last article, I discussed the different types of financial advisors and the various settings they work in. In this article, I’ll explain how financial advisors are compensated and what that means to you, should you choose to work with one.

In the third and final article in this series, I’ll discuss how to choose a financial advisor or decide to go the do-it-yourself route.

Some know, but most don’t

According to a 2017 Personal Capital study, of the 60% of all Americans who are investors, only “21% of [them] know they pay fees on their investment accounts but are not sure what they pay in investment fees, while 10% of investors don’t even know if they pay any fees.”

More recent surveys suggest fee awareness has improved somewhat since 2017, driven by increased regulatory disclosure requirements under Regulation Best Interest (Reg BI) and greater media attention to the impact of fees on long-term returns. A 2024 survey by the CFP Board found that approximately 45% of investors now report knowing what they pay in advisory fees, up from about 30% in 2017.

However, “knowing you pay fees” and “understanding total all-in costs” remain distinct. Many investors still don’t fully grasp how investment expense ratios, platform fees, and advisory fees compound to create total costs that can significantly impact long-term wealth accumulation.

According to the 2017 study, approximately one-third of investors either didn’t know whether they paid any fees or, if they did, didn’t know how much. In fact, many were paying more than they thought. That’s because some fees are obscured by performance reporting or withdrawn and accumulated over time. It can also be confusing because some fees are charged to the advisor, while others are charged to the investment managers of the recommended funds.

I’ve been providing financial counseling and coaching for several years, primarily through my local church. I have a fair amount of anecdotal data from people I’ve worked with who have used financial advisors. Some general observations based on that experience:

Many people…

- Don’t know specifically what they’re invested in or why

- Don’t understand what commissions, investment fees, and portfolio management fees are costing them

- Don’t know (or correctly understand) how their advisor is compensated

- Have been sold products they didn’t necessarily need because they generated high commissions for their advisor

You need to know what an advisor and your investments are costing you, and then assess whether they’re worth it to you. Both questions can be challenging to answer.

Before I go further, I want to make some crucial points, lest I be misunderstood:

First, I want to emphasize that there are many very good, well-qualified, and committed financial advisors. Sure, some are not—but they’re the exception rather than the norm. The trick is finding a good one you can trust (Matthew 13:26).

Second, I want to stress that financial advisors need and deserve to be paid for their services, just like you and I do (Luke 10:7). You wouldn’t work for nothing, and neither would I (unless volunteering time, of course). The question isn’t whether advisors should be paid but whether what you’re paying is fair and represents good value.

Third, a significant percentage of financial advisors are not as experienced, well-qualified, devoted, and successful as you might think (Matthew 24:4). That’s because many are really salespeople, and when compared with other professions (such as attorneys and CPAs), the barrier to entry is fairly low. It’s much higher for Certified Financial Planners.

Many financial advisors are trained to push specific products for their employers. There’s nothing wrong with that per se (that’s what salespeople do), but you need to know if that’s the case, as they may be more devoted to their employer and their own sales commissions than to you.

Also, although the requirements to become a financial advisor are relatively low (pass a couple of exams; no experience or academic prerequisites for entry-level positions), some individuals are presenting themselves as experts who may have no more than one or two courses on the subject and very little professional or life experience. (Plus, their personal finances could be a wreck and you’d never know it—the Mercedes might be leased.)

Understand your total costs

Although this article focuses on how advisors are compensated, it’s essential to consider their fees in the broader context of total costs.

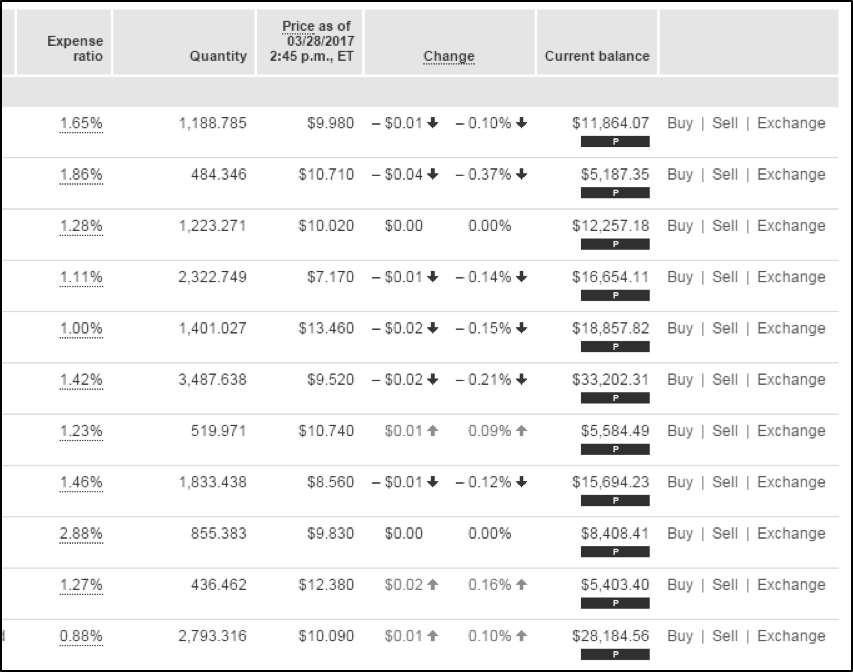

Back in 2017, a friend who was concerned about fees asked me to review his IRA portfolio. (I’ve done many of these reviews over the years.) He sent me a snapshot showing his holdings and their expense ratios (I’ve removed the company and mutual fund names):

Look at those expense ratios. The funds in his portfolio averaged approximately 1.5%. But that was in addition to the 0.75% fee he paid to the investment management firm he worked with. That was 2.25% of a $160,000 portfolio, or $3,600 a year.

He’s a very bright individual, but he didn’t fully understand the total charge until he took a closer look. He later wisely decided to go the do-it-yourself route, transferred his assets to Fidelity, and created a well-diversified portfolio using low-cost index funds with expense ratios around 0.03-0.10%.

That 2.25% total cost, compared with what he could have paid (perhaps 0.05-0.15% for index funds with no advisory fee, or 0.80-1.00% with a modern robo-advisor or low-cost advisory service), makes an enormous difference over time.

On a $160,000 portfolio:

- At 2.25% annual fees with 7% gross returns = 4.75% net, growing to $315,000 in 20 years

- At 0.85% annual fees with 7% gross returns = 6.15% net, growing to $525,000 in 20 years

- At 0.15% annual fees with 7% gross returns = 6.85% net, growing to $610,000 in 20 years

That’s the difference between $315,000 and $610,000—nearly double—from fees alone. This is why understanding total costs matters so much.

This example is a good reminder that the total cost for a managed investment portfolio isn’t just the advisory fee. You also have to pay the costs associated with the investments, as well as any other custodial and administrative charges.

And they can really add up. Financial planning blogger Michael Kitces wrote in 2017 that “a recent financial advisor fee study from Bob Veres reveals the true all-in cost for financial advisors averages about 1.65%.”

That’s right off the top and can be a considerable amount of money in larger portfolios, particularly if they’re conservatively invested and only growing 4-5% annually. The “all-in cost” includes the underlying investment expenses (mutual funds and/or ETFs), transaction costs, and various platform fees.

The advisory fee landscape has changed substantially in recent years. According to more recent data from industry surveys:

Average advisory fees have declined from approximately 1.00% in 2017 to 0.85-0.90% in 2025 for comparable account sizes. This compression has been driven by:

- Robo-advisor competition is forcing traditional advisors to justify their fees

- Increased transparency from Regulation Best Interest disclosure requirements

- Zero-commission trading eliminates transaction costs

- Ultra-low-cost index funds (many below 0.05%) are becoming standard

Typical all-in costs for professionally managed portfolios in 2025:

- Low-cost robo-advisor + index funds: 0.25-0.40% total

- Hybrid robo/human advisor + index funds: 0.40-0.60% total

- Traditional advisor + index funds: 0.90-1.15% total

- Traditional advisor + active funds: 1.40-2.00% total

The friends I’ve worked with who are still paying 2%+ total are increasingly rare and, frankly, are probably overpaying unless they’re receiving extraordinarily comprehensive services.

The research Kitces cited showed that financial advisors typically set their assets-under-management (AUM) fee schedules not only at a single rate but also on a sliding scale for both smaller and larger account balances. As his research found, the median advisory fee for assets under management up to $1M was 1%. However, many advisors charge more than 1% (especially on “smaller” account balances), and often substantially less for larger dollar amounts, with most advisors incrementing fees by 0.25% at a time (e.g., 1.25%, 1.00%, 0.75%, and 0.50%).

Fees, fees, and more fees

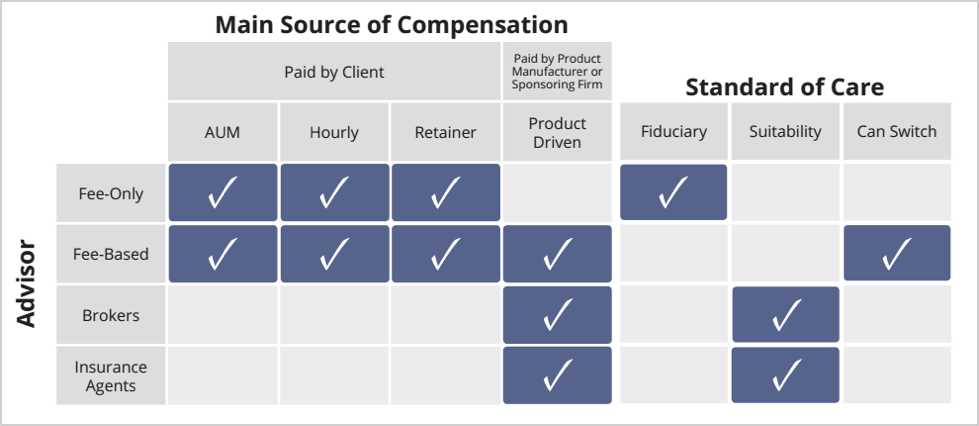

A percentage of AUM is only one way advisors charge for their services. Here’s an excellent chart from retirement planning expert Wade Pfau that shows the various ways financial advisors are compensated, aligned with the “standard of care” discussed in my previous article (fiduciary or suitability):

As shown in the chart, there are four main ways financial advisors are compensated:

- Assets Under Management (AUM) – fees based on a percentage of assets under management

- Hourly fees and fee-for-service – “pay as you go” for specific services

- Retainer – such as a flat annual fee or monthly subscription

- Product-driven – typically via sales commissions

You can also see there’s a direct correlation between fee-only advisors and a fiduciary standard of care. Brokers and insurance agents historically adhered to the suitability standard, while fee-based advisors (hourly or fee-for-service) may fall under either standard.

Several new or expanded compensation models have gained traction:

Monthly subscription fees: A growing number of advisors now charge flat monthly fees (typically $100-500/month) rather than AUM percentages. This model appeals to younger investors with lower balances and strong incomes, and to retirees seeking comprehensive planning without AUM-based fees that penalize them for having saved successfully.

Hourly-only planning: More CFP professionals now offer hourly-only comprehensive planning with no ongoing relationship, charging $150-400/hour for 5-15 hours of work to create a complete financial plan. Clients then implement on their own or return annually for updates.

Flat-fee comprehensive planning: Annual flat fees of $2,000-10,000 for comprehensive planning without ongoing portfolio management have become more common, appealing to DIY investors who want professional guidance on strategy but prefer to execute themselves.

Hybrid models: Many advisors now combine AUM fees for investment management with additional flat fees for comprehensive planning services, recognizing that portfolio management and life planning are distinct services that warrant different compensation structures.

Let’s review each traditional fee structure and assess how it may benefit or harm you, given potential conflicts of interest and total costs.

Asset-based fees (assets under management)

These advisors could work for any company providing investment management services—banks, brokerages, mutual funds, small advisory firms, etc. Most robo-advisors also use this pricing model. The advisor is paid based on the size of assets under management (AUM), typically determined by a percentage of your total assets.

Larger accounts usually carry lower percentage fees, while smaller accounts carry higher percentage fees. As your portfolio grows, the advisor receives more fee income in absolute dollars. If it shrinks, they receive less. In that sense, they’re incentivized to help you grow your assets and minimize losses—their interests are aligned with yours regarding portfolio growth.

This is why some advisors, especially successful ones, have minimum portfolio sizes. Smaller portfolios simply aren’t worth their time if they’re only earning 0.5% annually. That’s why advisors typically charge a range of fees—usually from 0.5% to 1.5% of AUM, with the percentage declining as portfolio size increases.

Current typical breakpoints for AUM fees in 2025:

- First $500,000: 1.00-1.25%

- $500,000 to $1 million: 0.75-1.00%

- $1 million to $3 million: 0.50-0.75%

- $3 million to $5 million: 0.35-0.50%

- Over $5 million: 0.25-0.35%

These percentages are lower across the board than comparable 2017 fee schedules, reflecting industry-wide fee compression. Many advisors now have minimums of $500,000 or $1 million, up from $250,000- $ 500,000 in 2017, as they’ve had to increase minimum account sizes to maintain profitability with lower percentage-based fees.

Most advisors deduct these fees directly from your account, which can be convenient for clients (no check-writing or budgeting hassle). The problem is that you may not notice it unless you carefully review your account statements or ask about it directly.

There are fewer potential conflicts of interest with this fee structure compared to commission-based compensation. However, there are some potential downsides:

Advisors benefit from maximizing your account size, even when that’s not optimal for you—such as when you’d be better served saving less and using money elsewhere, liquidating some assets to pay down debt, or maintaining a larger cash cushion for emergencies.

Smaller portfolios may receive less attention than clients with larger ones (1% of $100,000 is $1,000/year, whereas 0.5% of $500,000 is $2,500).

You pay regardless of service level. If your advisor spends minimal time with you in a given year, you still pay the full percentage fee.

You need to be aware of variations within this model. “Fee-only” advisors who charge only based on AUM are more likely to recommend lower-cost investments for your account, minimizing overall expenses and helping your assets grow faster. “Fee-based” advisors may be able to collect sales commissions in addition to the percentage fee charged on assets, creating potential conflicts of interest.

Hourly fees and fee-for-service

In this case, you pay the advisor (or planner) by the hour or for a particular service. For example, you may pay them to perform a risk analysis on your current portfolio, run a retirement planning model, create a comprehensive financial plan, or provide Social Security claiming analysis.

Since the hourly rate isn’t tied to any other measure or the purchase of specific products, you can be reasonably confident you’re getting objective advice. This can be especially valuable if you’re willing and able to implement the recommendations yourself, thereby eliminating ongoing fees.

As with attorneys and accountants, hourly rates or fees-for-service vary widely from one advisor to another. A highly experienced advisor, or someone with in-depth knowledge in a specialty area such as retirement or estate planning, will charge more. Less experienced advisors charge less.

Current typical ranges for hourly and project-based fees in 2025:

Hourly fees:

- Entry-level advisors: $150-200/hour

- Mid-career CFPs: $200-300/hour

- Senior/specialist CFPs: $300-500/hour

Project-based comprehensive planning:

- Basic financial plan: $1,500-3,000

- Comprehensive retirement plan: $3,000-6,000

- Complex estate/tax planning: $5,000-10,000+

These fees have increased moderately since 2017 but represent better value than AUM-based fees for many clients, particularly those with substantial assets who don’t need ongoing portfolio management.

One thing to keep in mind is that any reasonable businessperson is looking for new business. If you come in as an hourly fee customer, they may try to convince you to sign up for ongoing services. Hourly or fee-for-service advisors may have an incentive to “over-plan”—that is, to recommend services you don’t really need.

Sales commissions

Typically, financial advisors employed by brokerages and insurance companies are paid on commission. They may also receive a small salary, but the bulk of their compensation comes from commissions on product sales.

In addition to commissions, if they meet their annual sales targets, they may receive bonuses. If they don’t, they make less and could even lose their jobs. If they exceed targets, they can earn additional bonus pay.

As you can see, commission sales can be a tough business—it can be challenging for the salesperson, and it can also have negative impacts on you. That’s because the advisor’s recommendations may be influenced by their compensation. The larger the commission, the more likely an advisor is to push you toward a particular investment product. Unfortunately, greed can become a driving factor (Ecclesiastes 5:10).

Since Regulation Best Interest took effect in June 2020, commission-based advisors face significantly higher disclosure requirements and must demonstrate that recommendations are in the client’s best interest rather than merely suitable. While commissions haven’t been eliminated, the regulation has:

- Required more transparent disclosure of commission amounts and conflicts

- Pushed many commission-based advisors toward fee-based or fee-only models

- Reduced the most egregious high-commission product sales

- Increased scrutiny of variable annuities and other high-commission products

Many broker-dealers have responded by shifting their advisor compensation structures from pure commission to salary-plus-bonus models that reduce direct pressure to sell products. However, commission-based conflicts haven’t been eliminated—they’ve just become more regulated and disclosed.

Commissions are paid in various ways. Many people believe that all their money goes into the investment they purchase, and that the investment company pays the salesperson out of its own pocket. Wrong! In most cases, commissions are deducted from the top, and your investment is reduced accordingly. Rarely does the investment company pay the advisor directly from its own profits.

One example is a front-end charge (called a “sales load”) on a mutual fund. Another is the commission for the sale of an annuity. If you invest $10,000 in a mutual fund with a 5% load, you would pay $500 in upfront loads. If you invest $100,000 in an annuity with a 5% sales charge, you pay $5,000 upfront.

Front-end sales loads have become much less common since 2017. Most major fund families now offer no-load share classes, and many broker-dealers have eliminated sales loads on mutual funds entirely in favor of fee-based compensation. However, they still exist, particularly for Class A shares sold through insurance agents and some traditional brokerages.

Similarly, annuity commissions remain substantial (often 5-7% for traditional annuities, 1-3% for lower-commission “fee-based” annuities), though disclosure has improved significantly under Reg BI.

That’s a big deal, especially if you consider what that money would be worth 20 years later if it had grown modestly at 5% annually. That initial $500 mutual fund load would have grown to $1,326, and the $5,000 annuity commission to $13,266.

Remember, many other fees may apply when you purchase an annuity, depending on the features and benefits you choose: guaranteed income riders, guaranteed lifetime withdrawal benefits, fees on the underlying investments, mortality and expense fees, and more. Some of these features may be desirable to you, but be sure you understand their cost.

There are also charges that occur on the “back-end” of some transactions. These are usually associated with products that have surrender or cancellation charges. In return, the investment company pays the salesperson directly rather than charging you up front. But if you bail early, you’ll pay directly, and maybe dearly. Early termination charges are standard in many life insurance and annuity products and typically last 5-10 years.

Finally, there are “trailing fees” or “residuals.” In this case, the salesperson receives an ongoing fee taken directly from your investment year after year. One significant problem is you may not even notice since they’re debited automatically and tend to be smaller amounts (typically less than 0.5% annually, though they accumulate over time).

Retainer

The most common form of this fee structure is a “flat annual fee” or a monthly subscription. This is a fixed amount you pay, regardless of portfolio size, number of transactions, or market performance.

Subscription-based advisory models have grown substantially since 2017, particularly appealing to:

- Younger professionals with high incomes but lower asset balances (for whom AUM fees don’t work)

- Retirees who want comprehensive planning without being penalized for having saved successfully

- People who want financial planning advice without ongoing portfolio management

Typical monthly subscription fees range from $100 to $500/month ($1,200 to $6,000 annually), depending on the complexity of services provided. Some advisors offer tiered subscription models with basic, standard, and premium service levels.

The advantage is predictability and no conflict around growing your portfolio. The potential downside is that advisors might do the minimum work necessary to retain you, since their compensation doesn’t increase with effort or results.

Which fee structure is best?

As we’ve seen, there are pros and cons to each compensation method. I have concerns with all of them.

I appreciate the fiduciary aspects usually associated with advisors who charge asset-based fees. What I don’t like is that you pay the fee on an ongoing basis, regardless of the level of service you receive year-by-year. That makes “fee-for-service” more attractive, as it’s a pay-as-you-go model.

Both methods may have fewer potential conflicts of interest than commission-based advisors. But with a commission-only approach, you only pay when your advisor/broker sells you something or purchases it on your behalf. That could reduce your overall costs, especially if those transactions are infrequent (assuming there isn’t excessive “churning” in your account that you don’t know about).

Here are my observations:

AUM fees can be worthwhile for comprehensive services that include tax planning, estate coordination, Social Security optimization, withdrawal strategy, rebalancing, and behavioral coaching. But they’re a waste if all you’re getting is a quarterly statement and annual rebalancing.

Hourly or project fees work well for DIY investors who need periodic expert guidance but prefer to handle day-to-day management themselves. The $3,000-5,000 cost of comprehensive planning is often a better value than paying 1% annually forever.

Robo-advisors provide exceptional value for straightforward situations with fees of 0.25% or less, automated rebalancing, and tax-loss harvesting. But they lack the behavioral coaching that matters most during crises.

Commission-based models are problematic even with Reg BI improvements. The conflicts are too fundamental. If you’re working with a commission-based advisor, ask yourself: Would they recommend this same product if it paid a 1% commission instead of 5%?

Hybrid models combining human guidance with robo-efficiency (charging 0.40-0.60% total) may offer the best balance for many retirees—low enough to preserve wealth while providing human support when it matters.

The “right” answer depends on your situation, but fee transparency and value alignment matter enormously.

And be careful about advisors who tell you their fees are being paid by the investments themselves—that somehow they “earn their keep” by buying, selling, and reallocating your assets so you earn more than “the market.” They do get paid, but that money has to come from somewhere, and it’s usually from commissions embedded in the products they sell.

The “which is best” question is difficult to answer due to the nuances involved. For example, an advisor who charges 0.75% AUM may tell you that’s a great value because they’ll enhance your returns by more than that, making them worth every penny—and maybe they are. Or they may argue that the upfront 5% sales charge is worth it because the investment is a top performer. If you’re purchasing an annuity, you may want add-on features you believe justify the additional expense.

But what if you could find an advisor who’s just as good but only charges 0.25% of AUM? (That happens to be the range most robo-advisors charge.) Wouldn’t that be the way to go? Perhaps, as long as you genuinely believe the value you receive justifies the cost and meets your specific needs.

How can you know?

In the next article, I’ll discuss how to choose a financial advisor in detail. But no matter who you select, be sure to get a full explanation of how they’re compensated before you hire them. Ask good questions and seek honest, direct answers. If the advisor is evasive or implies that fees don’t matter, leave and look elsewhere.

If they’re paid on AUM or on a fee-for-service basis, ensure you know the applicable percentages or rates and how and when you pay them. If they’re commission-based, make sure you know how much they’ll receive for any investments or insurance products they recommend, and exactly how it will be deducted from your account.

Finally, ensure you understand the costs associated with the investments in your portfolio, in addition to what you’re paying the advisor. That can be a little tricky because they’re usually deducted by the investment management company before earnings are reported, making them less visible.

The good news is that the advisory fee landscape has improved substantially for consumers since 2017:

Greater transparency: Reg BI requires clearer disclosure of all fees and conflicts of interest. It’s much harder for advisors to hide total costs than it was a decade ago.

More options: The explosion of robo-advisors, subscription models, and project-based planning gives consumers choices beyond the traditional 1% AUM model.

Fee compression: Competition has driven fees down across the board. What cost 1.5% in 2017 might cost 0.85% in 2025 for comparable services.

Better alignment: New models, such as monthly subscriptions and project fees, better align compensation with value delivered rather than just portfolio size.

That said, many advisors still charge too much for too little. Your job is to understand exactly what you’re paying, what you’re getting, and whether the value justifies the cost. Do this carefully, and you can enter any advisory relationship as a well-informed investor, making the best decisions possible for your retirement stewardship.