I have written about the significant changes in the U.S. and the world economies and how they might impact our retirement portfolios.

These changes are not all bad (for example, many people think it’s good that the Fed wants to take a more passive role in controlling the U.S. economy—after a round of quantitative tightening, of course). It’s probably a good idea for interest rates to rise to normal levels.

But these changes are causing some significant pain for everyone: inflation (much higher prices for things like gas and food), stock and bond market volatility (affecting savers and retirees alike), and higher interest rates for loans (credit cards, auto loans, and mortgages).

This is occurring as the economy is recovering from the debilitating effects of the worst of the COVID pandemic.

These changes are causing many of us to adjust our lifestyles, investments, and economic expectations. It has hit young families with lower incomes and retirees pretty hard—especially those like me who rely on their savings for a portion of their retirement income.

In my last article, I wrote about making the retirement decision in this challenging economic climate. Whether to retire during these times is a difficult enough question. Many have probably decided to delay it.

But what if you recently retired?

One of the hardest hit groups is those who retired at the peak of the stock market “bubble,” which would have been late 2021, but any time between mid-2020 and then. A big reason is the “sequence of returns” problem.

I’ve written about this before, but in this article, I go deeper. It’s a significant risk, but as I’ll show you, there are ways to mitigate it.

What it is

“Sequence of returns risk” (SRR) is a sophisticated-sounding description of a relatively simple thing: the risk of lower or negative returns early in retirement while you are spending from it.

In other words, a “double whammy” effect (not a technical, financial term) such that you are withdrawing money from a portfolio while it’s declining in value, thereby accelerating its losses.

It’s not the short-term losses that matter (although they can be painful); it’s the long-term effects.

We’re currently in a down market year and we’re experiencing its effects. But we don’t know how it will finish, and we also don’t know how it will perform next year. Therefore, we don’t know how much sequence risk the fed’s quantitative tightening policies will create—only time will tell.

Generally, retiring during a bear market (if you can), with stocks at lower valuations, is better for avoiding SRR than retiring near the top of a bull market, with stocks at high valuations or overvalued.

Why? Because if you retire during low valuations, there’s a better chance they will go up in the future. If stocks are over-priced, there’s a greater chance they’ll do down.

How it does damage

Let’s say that just as you retire, you’re withdrawing 4% and your portfolio falls by 20%. Your portfolio will be down a total of 24% in the first year depending on withdrawal timing.

If you were selling assets (stocks and bonds) to fund those withdrawals, you’ll have 24% fewer assets to generate growth and income in the future. Another year or two of bad returns combined with 4% withdrawals compounds the problem.

In my last article, I discussed whether now is a good time to retire. When you first read the title, you may have thought, “What a dumb question, this is the worst time to retire.” You’re probably wise to be reluctant right now, all things considered.

I provided some simple ways of assessing your current financial condition in that article. If you plan to retire at the end of 2022 or early 2023, you might be rethinking that decision. Or perhaps you can still afford to despite the losses likely to add up this year.

I didn’t discuss sequence risk in that article. Still, it’s a genuine threat, even if your current financial condition looks pretty good, and especially if we go into a prolonged recession.

Prolonged poor annual market returns early in a retiree’s series of returns can cause problems, but they can also happen due to a quick, precipitous crash like we had in 2008 when losses in a single year were extremely high.

Usually, sequence risk is relatively low, but during major economic upheavals, it occurs in bouts.

Part of a bigger picture

Although a sequence of negative returns can have a damaging impact, it’s only one determinant of premature portfolio depletion; it’s part of a bigger picture.

Many other things affect portfolio sustainability, such as life expectancy, the market returns themselves, the volatility of those returns, the amount you choose to periodically spend, how flexible you are with your spending, and the starting value of your portfolio.

The simplest way to explain how all these things work together is the smaller our starting savings account balance, and the longer we live, or the more we spend, the more we depend on higher returns (or less volatility of them) to maintain our portfolio’s sustainability. And some of these factors have a greater impact on it than others.

Aging is a critical variable in all of this because it affects everything else. All of the risks to our portfolio go up as we age. Most importantly, aging affects our life expectancy and the size of our portfolio (the longer we live, the more we have to spend from it).

Therefore, the size of our portfolio and our life expectancy at any given time are the most important factors—market volatility, and sequence risk notwithstanding. We simply don’t know (and probably can’t say for sure) how much money will be left in our retirement account in 10 or 20 years or whether we will live that long.

Sequence and longevity risk

“Sequence risk” enters an already uncertain picture with all its different variables as we periodically spend from a volatile portfolio of stocks and bonds. ”Longevity risk” is simply the risk that you outlive your savings.

Sequence risk and longevity risk are closely related. The longer you live, the more damaging the effects of an undesirable sequence of returns can be. Why? Because sequence risk means you take more chips off the table before you have a chance to play the game (sorry for the bad metaphor).

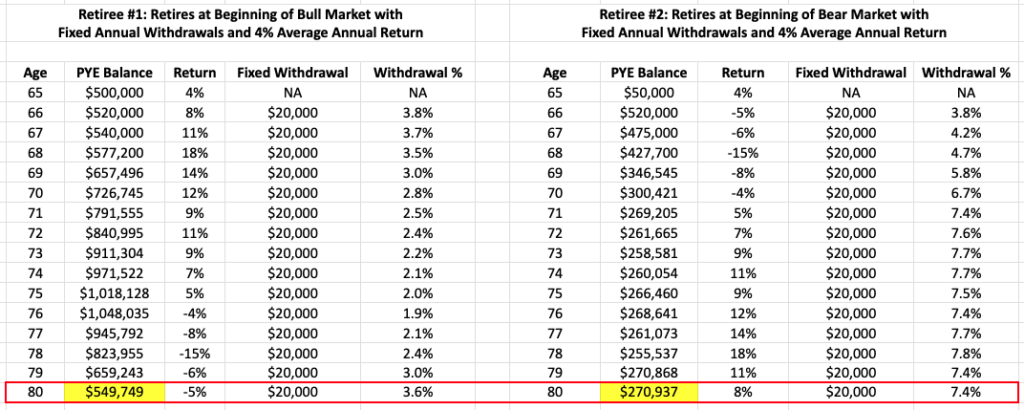

To illustrate, here’s a chart that shows how sequence of returns risk works over long periods—in this case, 15 years. It shows two identical retirees, with the difference being that retiree #1 retires at age 66 during a bull market, and retiree #2 retires at the same age during a bear market:

(In this chart, “PYE Balance” is Prior Year End (Account) Balance; “Return” is Investment Returns; “Fixed Withdrawal” is the Fixed Annual Withdrawal Amount; and “Withdrawal %” is the Actual Withdrawal Percentage per Year.)

As you can see, annual gains and losses are the same but reversed. Therefore, the average annual return for both retirees is identical after 15 years (4%). However, retiree #2, who retired at the beginning of a sequence of down market years, has about 50% less in their account than the one who retired at the start of a multi-year bull market.

And that was despite the fact that there were only five years out of 15 with negative returns in this example! Furthermore, the negative years weren’t terrible (they ranged from -5% and -15% per year).

A critical factor that exacerbated the situation for retiree #2 was maintaining a fixed annual withdrawal of $20,000 regardless of his account balance. That equates to 3.8% in year one but rises to over 7% by year six and stays in that range to age 80. (You may recall that 3% to 4% is generally considered a “safe” withdrawal rate to help your savings last.)

Hopefully, most people wouldn’t automatically maintain such a high withdrawal rate from a portfolio that has lost half its value over six years.

This example can be alarming, especially if you’re in the fixed annual withdrawals camp. As the table shows, five or six years of a down market while you’re withdrawing the same amount each year can be devastating.

But take heart—such scenarios are uncommon; most bear markets last two to three years. Plus, most people will adjust their withdrawal strategy to compensate, and if they do, it can significantly impact mitigating sequence risk.

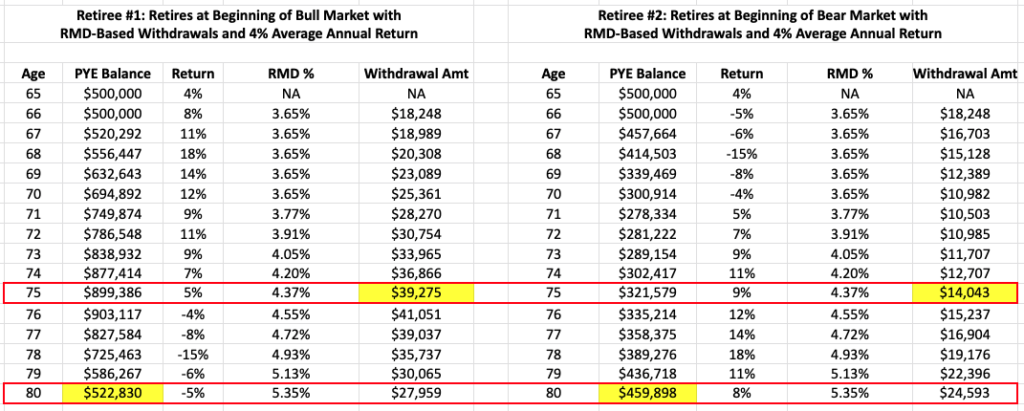

Take a look at another example. It shows the same scenario for two retirees but with one big difference: Instead of a fixed annual withdrawal, they are using their RMD percentage with a low withdrawal rate that increases at age 72 (which is now when RMDs must begin by law). The RMD is a percentage is applied to the prior year’s end balance.

(In this chart, “PYE Balance” is Prior Year End (Account) Balance; “Return” is Investment Returns; “RMD %” is the “Required Minimum Distribution Percentage”; and “Withdrawal Amt” is the Actual Withdrawal Amount per Year.)

As you can see, despite the bear market that retiree #2 had to go through early in retirement, their account balance at the end of 15 years was very close to that of retiree #1’s. That’s nice, but the news isn’t all good.

Look at each retiree’s retirement income at age 75. Retiree #1 is withdrawing their RMD of $39,275, but retiree #2 is withdrawing only $14,043, which is less than half (and probably much less than what they need to live on).

Because of positive returns in the following years, retiree #2 will make up some lost ground, but she will never get to where retiree #1 is regarding account balance or withdrawals.

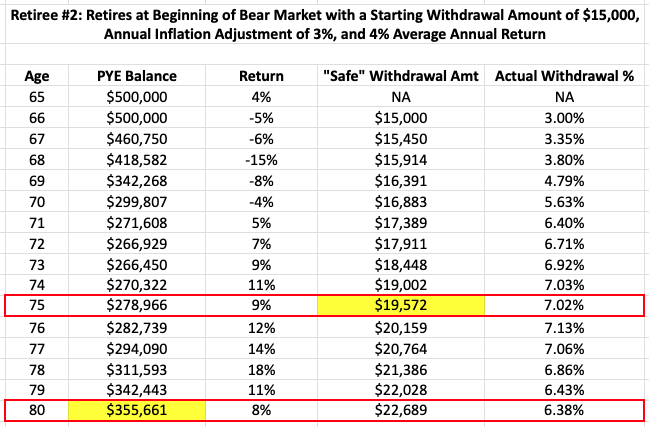

Withdrawing more (well over the RMD) to fund spending needs will be problematic for retiree #2. In the following example, I assume that retiree #2 can live on withdrawals starting at $15,000 annually, adjusted by 3% for inflation each year. (The actual withdrawal percentage will far exceed the RMD requirement.) Let’s see how that works out:

(In this chart, “PYE Balance” is Prior Year End (Account) Balance; “Return” is Investment Returns; “Safe Withdrawal Amt” is the Fixed Annual Withdrawal Amount; and “Actual Withdrawal %” is the Actual Withdrawal Percentage per Year.)

In this case, her income at age 75 (the “safe withdrawal amount” in the table) is higher than it was with RMDs but not nearly as high as retiree #1. As you can also see, her actual withdrawal rate is very high at that age.

Her account balance at the end of 15 years is less than if she had taken RMDs, but having 71% of her original account balance of $500,000 remaining at age 80 isn’t so bad. This assumes she can live on $22,689 (plus any Social Security and other income) at that age.

In all the scenarios for retiree #2, we see the damaging effects of sequence risk, but we also see how we can mitigate them somewhat with flexible spending approaches but at the cost of less income.

Mitigating factors

We can conclude from these examples that sequence of returns is a real risk to the long-term sustainability of a market-sensitive retirement portfolio. The highest ‘cost” of sequence risk is the loss of capital and its compounding returns.

The situation is further exacerbated when we spend from a portfolio by selling assets during a time we are losing capital due to a falling market; our portfolio balance further loses the money we spend plus all the potential future compounded gains on the assets we sold.

Another contributing factor is periodic spending, which, if too large, can result in further portfolio depletion. While losing 100% of a retirement portfolio due to SRR is highly unlikely, even with SRR and excessive spending, an extremely poor sequence of returns combined with unsustainable spending could lead to portfolio destruction.

Because we have no control over the sequence of returns we receive, nor can we predict the sequence, we can only look for ways to mitigate its effects.

1) Adjust your spending.

Variable spending strategies (especially reducing spending when portfolio value is down) won’t eliminate SRR. But they can lower the probability of premature portfolio depletion by not unwisely spending the same fixed amount annually when savings dwindle.

The problem with variable spending is that we may be unable to maintain our standard of living. When our “safe” variable spending drops below our non-discretionary expenses for an extended period, we still have to buy food and pay the electric bill and our medicare premiums, even if we are at an “unsafe” level of spending from our portfolio.

2) Adjust your asset allocation.

Another way to mitigate SRR is to change your stock to bond allocations, reducing stocks and adding less volatile bonds. This protects against stock market declines but not rising interest rates or inflation. (I shifted from a 60%/40% stock to bond ratio before retirement to 40%/60% when I retired.)

3) Purue a “safety first” strategy.

Another option is to pursue a ”safety first” strategy which relies on assets like a Single Premium Immediate Annuity (SPIA) or TIPS bond ladder to provide income that is not subject to market risk in the event of portfolio failure. (Learn more about this strategy here.)

4) Maintain a cash buffer.

Maintaining a cash buffer that you can spend down when the market is down may prevent you from having to sell depreciated assets, further increasing sequence risk. (I discussed this in more detail here.)

Key takeaways

Most people think and care about the potential returns of their retirement portfolios, whether oriented mainly toward growth, income, or both.

But in reality, the sequence of those returns matters more than average returns (which is why I used the same average annual returns in each of the examples above). For our portfolios to be sustainable over a long retirement, we need a fortunate sequence of portfolio returns much more than we need really good returns.

Fortunately, as we have seen, there are some things we can do to mitigate SRR. It never goes away, but it can become relatively small if your wealth is (or becomes) very large relative to your spending needs and remaining life expectancy — when your portfolio performs well throughout retirement. Sequence risk can become quite high under the opposite circumstances.

The key takeaways are that the sequence of the returns your retirement portfolio experiences is a major determinant of portfolio sustainability. But the most crucial factor is how long you will be retired (which goes to life expectancy and longevity risk). And as we know, none of these is predictable for an individual or couple.

For that reason, we do all we can to mitigate known risks (Prov. 27:12). We also hold our assets ‘loosely,’ thus avoiding anxiety and fear in the knowledge that it all belongs to God, and in his sovereignty, he has chosen to give it to us to manage in his behalf (Matt. 25:15-29).

Finally, we must put our ultimate trust in our heavenly father who loves us and who has promised to help and care for us:

For I, the LORD your God, hold your right hand; it is I who say to you, “Fear not, I am the one who helps you (Isaiah 41:13, ESV).