This article is part of the Retirement Financial Lifestyle Equation (RFLE) series. It was initially published on January 25, 2023, and updated in January 2026.

In the last two articles, I discussed how retirees (and others) use bonds as part of a diversified portfolio because of their stabilizing effect during stock market volatility.

Bonds can also be an excellent source of income and may provide capital gains under some economic scenarios (especially falling interest rates).

We’ve also seen that individual bonds are best used for “liability matching” to future spending needs. Many retirees may find that building a bond ladder with individual bonds of varying maturities can offer benefits that bond funds and ETFs don’t.

In the three years since I wrote this article, bond ladders—particularly TIPS ladders—have become significantly more attractive due to improved real yields and new research from Morningstar. Their 2025 study shows that a 30-year TIPS ladder can support an inflation-adjusted starting withdrawal rate of 4.5% with 100% success (full depletion at year 30). This is a game-changer for retirement income planning.

Additionally, I continue to hold TIPS through a fund rather than building a ladder, and I’ll explain in this updated article why that decision remains appropriate for me, while acknowledging that TIPS ladders have become compelling for many retirees—especially those with specific known spending needs and portfolios over $250,000.

In this, the third in a series, I’ll examine the benefits of building a bond ladder versus investing in bond funds, particularly in certain situations.

Rolling versus non-rolling bond ladders

There are two types of bond ladders: rolling and non-rolling. Which one you choose will depend on why you are selecting a bond ladder over a bond fund in the first place, because, as we’ll see, a bond fund behaves much like a rolling bond ladder.

In the last article, I described how a rolling bond ladder would work for a single bond. You purchase a one-year bond initially for $50,000 and then “roll it over” each year by buying a new bond at the prevailing interest rate, which may be higher or lower.

But in reality, very few people would build a bond ladder with a single bond (a ladder with a single rung is a step stool, I think).

A better alternative, as shown below, might be to purchase five bonds (A through E), each for $10,000 and with a different duration (from one to five years), and at the current coupon (interest rate) for that term (the second row in the table; interest rates are illustrative).

Then, after spending the coupons for income, you could roll over each bond upon maturity by purchasing a new five-year bond that begins coupon payments in year two and matures in year six.

As shown in the table, the first bond (A) would mature in one year and would pay a coupon of 3.5%. You would receive your original $10,000 plus one year of coupon payments ($350) for a total of $10,350.

If you reinvest in another bond instead of spending the money you receive from the matured bond, you’ve created a rolling ladder because you roll over the money you receive from each maturing bond to a new five-year bond, extending the ladder to year six.

In the above example, you would roll bond (A) into a new five-year bond (F), which would start paying coupons of 3.5% in year two and will mature in year six. That process would continue for bonds B thru E as they mature, making the ladder non-depleting.

A rolling bond ladder is not necessarily designed to address a date-certain future liability, such as a year of college tuition or retirement income. A rolling ladder behaves more like a bond fund and will exhibit similar returns over long holding periods.

The advantage of a rolling ladder over a bond fund is debatable—you get slightly more control over specific bond selection and maturity dates, but you sacrifice diversification, professional management, and simplicity. For most retirees, a well-chosen bond fund will perform similarly to a rolling ladder with far less effort.

That’s why I continue to use bond funds rather than rolling ladders—the benefits don’t justify the management complexity for my situation.

To fulfill a future spending liability, such as a year of retirement income, a non-rolling ladder of individual bonds is more suited to that purpose than a rolling ladder or bond fund.

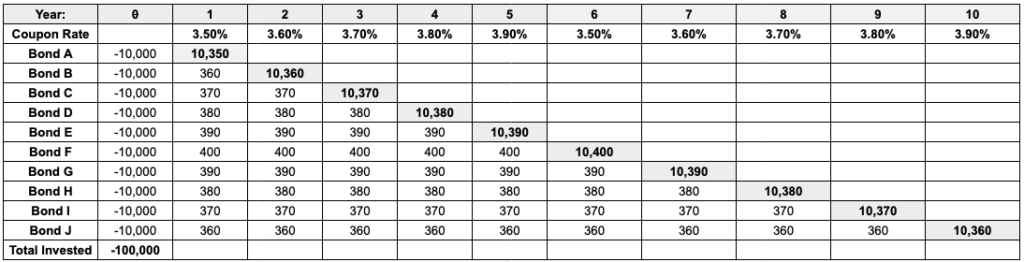

For example, if you need money each year for ten years and want to protect your principal from interest rate risk, you might set up a 10-year bond ladder as shown.

You could purchase ten bonds, each for $10,000 and with a different duration (from one to ten years), and at the current coupon (interest rate) for that term (shown below the year in the table; interest rates are illustrative).

The first bond (A) would mature a year from now and would earn interest of 3.5%. You would receive your original $10,000 plus interest of $350 in year one for a total of $10,350. The next bond (B) would mature in year two, and you’ll get back your original $10,000 plus $360 of interest, plus one year of coupons for two years ($720) for a total of $10,720 ($720 + $10,000).

With each passing year, each remaining bond (C thru J) has one less year to maturity. This scenario fully depletes the ladder after the last bond matures in ten years. Most retirees build ladders based on their life expectancy.

With current Treasury yields at 4.0-4.5% and TIPS real yields at approximately 2% plus inflation adjustments, non-rolling ladders have become genuinely attractive for the first time in over 15 years. This is particularly true for TIPS ladders, which we’ll discuss in detail below.

Because bonds make coupon payments monthly, semi-annually, or even annually, if you need $10,000 of income each year from your ladder, you might “discount” each bond purchase by the total income you expect to receive each year from the other bonds in the ladder.

For example, when bond E matures in year five, you’ll receive coupons from all the other bonds still outstanding. Therefore, you could purchase a five-year bond with a face value less than $10,000 to meet your spending requirement of $10,000 in year five when combined with the coupon income from bonds F through J. (The math for this calculation is complex; you’ll need a spreadsheet or an online bond ladder tool.)

Whether you do this would depend on what you expect your future spending needs to be (and inflation, since we’re talking about “nominal” non-inflation-adjusted bonds here).

Bond ladders versus bond funds

The primary reason for building a non-rolling bond ladder is to take advantage of the total return of the principal when bonds mature. Even though the “on paper” value may fluctuate, you’re assured of getting your principal back plus interest (unless you spend it for income before the bond matures).

Not only is each bond guaranteed not to lose value over its term, but the bond ladder won’t lose money over its term (which was ten years in the example above).

Some view this as a safer option for fixed-income investments than a bond mutual fund or ETF, which, as we have seen, works more like a rolling bond ladder.

For someone who needs to satisfy a date-specific future spending need, a non-rolling ladder may be superior to a bond fund. You could use it to match future cash flows from the return of principal and earned interest to future spending needs that protect the bond portion of your portfolio from interest rate changes.

Looking back at the bond market through the 2022-2025 period, I can now provide more nuanced guidance:

The 2022 experience illuminated differences:

- Individual bond ladder holders: Saw their bonds’ market values decline but were unaffected if holding to maturity; continued receiving their fixed coupon payments

- Bond fund holders: Saw fund NAV (Net Asset Value) decline by 13-15%; distributions continued but fund values were down significantly

- The outcome by 2025: Bond funds fully recovered their losses; individual bondholders got their principal back as bonds matured but had locked in lower yields if bonds were purchased 2019-2021

What this taught us:

- Both approaches “work” but serve different purposes

- Individual bonds provide price certainty if held to maturity

- Bond funds provide liquidity, diversification, and professional management

- The “safety” of a bond ladder is psychological as much as financial

It must be noted, however, that the value of individual bonds held in a personal bond ladder fluctuates just as the net asset value (NAV) of a bond fund does (since the fund’s NAV is an aggregate of the NAV of all its bond holdings). The daily price fluctuations of an individual bond will be very similar to those of a bond fund with the same duration.

You shouldn’t be too concerned if you plan to hold the individual bonds to maturity. Nor should you be overly worried by the fluctuation of a bond fund NAV if you are primarily interested in the income it’s generating and don’t need to liquidate shares to fund spending in the near future.

Still, a bond ladder can provide some mental and emotional comfort. Bond funds and ETFs can seem opaque, and when you only see fluctuating prices (or significant losses as many experienced in 2022), it can be troubling since most retirees own bonds for relatively “safe” income. They (including me) don’t like to see their value decline as they did in 2022.

Having lived through 2022’s bond losses in my bond funds, I can confirm the psychological challenge was real. Seeing double-digit losses in what were supposed to be “safe” investments was disconcerting. However, I maintained my positions, and by 2024-2025, all my bond funds had fully recovered and were yielding 4-5%, substantially higher than the 1-2% yields in 2020-2021.

An individual bondholder with a ladder purchased in 2019-2021 would have avoided the paper losses but would now be locked into 2-3% yields as those bonds matured and required reinvestment at current rates. There’s no clear “winner”—just different trade-offs.

A bond ladder, on the other hand, feels more transparent. You know exactly when each bond matures and exactly how much you’ll receive. But if you build a rolling bond ladder and continuously reinvest your principal, your overall returns may not differ significantly from investing in a bond fund or ETF—and you’ll have much more management work.

A better ladder?

Another big issue with non-rolling bond ladders that match withdrawals with matured bonds is that you’ll get your principal and accrued interest back, but it won’t be adjusted for inflation. So, although you may receive your $10,000 investment back in full in five years, it’ll be worth less due to inflation—a lot less if inflation has been extraordinarily high over that period.

From January 2020 to December 2025, cumulative inflation was approximately 22%. This means that $10,000 in 2020 had the purchasing power of only $8,197 in 2025. A traditional nominal bond ladder would return your $10,000, but you’ve lost 18% of your purchasing power. For a 30-year retirement, this erosion is devastating.

This is why inflation protection is crucial for retirement income planning.

The remedy may be Treasury Inflation Protected Securities (TIPS). These are U.S. Treasury bonds that compensate for inflation. The U.S. Treasury is considered the safest bond issuer in the world. Many consider TIPS the safest of the safe because, unlike all other Treasuries, TIPS protect against inflation.

TIPS bonds pay their coupon rate of interest semi-annually. At maturity, the Treasury increases the amount of principal you are repaid to compensate for inflation over the bond’s life.

When I wrote this article in January 2023, TIPS real yields were approximately 1.5-1.8%. As of December 2025, TIPS real yields are approximately 2.0-2.2%, which are the highest real yields since 2009. This makes TIPS significantly more attractive than they’ve been in over 15 years.

We’ll discuss TIPS and TIPS ladders in greater depth in future articles.

Bottom Line

The question “to ladder or not to ladder?” has become more nuanced, particularly for TIPS ladders, which have emerged as a validated and powerful retirement-income tool.

Remember: Wise stewardship means matching tools to needs. TIPS ladders are powerful tools—but only if they match your specific retirement income needs, risk tolerance, and portfolio size. Don’t build a ladder just because someone says it’s optimal. Build it because it solves a specific problem you have.