In the last two articles, to help you answer the “Can I retire?” question, I went over an approach for calculating your essential living expenses and for determining whether you will have enough income from “guaranteed” sources to cover them.

I also looked at what you could do regarding withdrawals from “non-guaranteed” sources, such as retirement savings, to cover any shortfall.

In this, the final article in the three-part series, I am going to discuss the “sustainability” of withdrawals and some of your options if you believe that your required withdrawal rate from savings is not sustainable over the remainder of your lifetime.

This step is one of the most critical aspects of financial planning in retirement as it relates to longevity risk, which is the risk that you will withdraw too much from your savings and run out of money before you leave this world.

It’s important from the outset to remember that, when it comes to our plans, there are no guarantees or absolutes in this world. God is ultimately in control of things, including our retirement (Job 42:2; Ps.135:6). We can only plan and adjust to circumstances as we are able based on the wisdom and guidance he provides while trusting in him for the rest. An abiding trust in the goodness and faithfulness of God must be the foundation for any well-laid-out plan we may have (Ps.13:5).

Begin with your required savings withdrawal rate

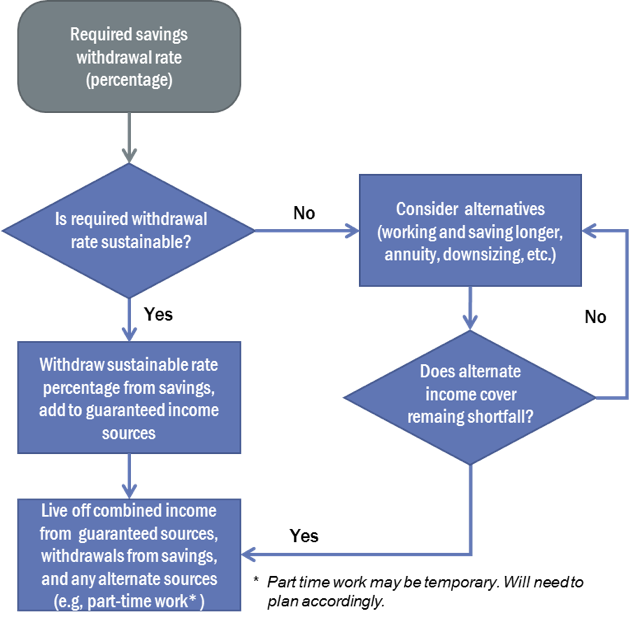

As you can see in the diagram below, the third section of the larger one I introduced in the first article, I begin this discussion with your “required savings withdrawal rate.” In the illustration I have been using, there is a shortfall of $15,750 which results in a required withdrawal rate of 3.5 percent from total retirement savings of $450,000.

I also discussed the implications of having a 30 percent lower savings balance which resulted in a required withdrawal rate of 5.0 percent, and a 30 percent higher balance resulting in a decrease to 2.7 percent.

Once you come up with your required withdrawal rate, you need to decide whether it is “sustainable,” meaning that you can withdraw that amount (hopefully, adjusted for inflation) each year for as long as you live without running out of money.

From there, as the diagram shows, things can go in a couple of different directions depending on what you decide.

What is “sustainability?”

To get at this question of sustainability of withdrawals from savings, I need to introduce the idea of “safe withdrawal rates.” If you read much about retirement planning, you have probably come across the term; it’s widely used in the financial industry but often misunderstood.

Ironically, when it comes to investing in the financial markets, especially stocks, there is no such thing as “safe” – in a relative sense, perhaps, but not in any absolute sense. The value of your investments will fluctuate based on the ups and downs in the markets, which are driven by multiple factors such as supply and demand, global politics, and macroeconomics.

We have been in a dramatic and unprecedented stock market upswing for almost ten years now with seemingly no end in sight. But if history is any indication, it won’t go on forever; market cycles never do. (As I write this, we are experiencing increased volatility in the stock market and the S&P 500 is down almost 10 percent.)

When you are young and are saving and investing for the long term, market ups and downs are not a problem. The best thing to do is just ignore them. That’s because, overall, over the course of many decades, the market has gone up. But when you are near or in retirement and need to start withdrawing from your savings, you are in a much different (and more precarious) situation.

A significant market downturn early in retirement can create “sequence of returns risk,” which can affect your required withdrawal rate.

Consider someone who retired around 2008, which was one of the worst years in stock market history. The Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA) declined a total of almost 34 percent for the year! If you take a 34% hit to your savings, you will have that much less to draw from, at least temporarily. Assuming your required withdrawal rate is 3.5 percent from savings of $450,000, and they are reduced 34 percent to $297,000, your required withdrawal rate would increase to 5.3 percent – not nearly as “safe” as 3.5 percent.

Now, to be fair, the market gained back 18.8 percent in 2009, but your savings would have still been 15 percent less than at the start of 2008. And over time, the markets recovered even further, reaching many new daily highs, at least until recently. In fact, in 2018 alone there were 13 new all-time highs on the S&P 500 before the recent correction.

Safe withdrawal rates

Most people try to mitigate sequence risk due to market volatility by supplementing their stock investments with fixed income – things like bonds, CDs, bank savings, etc. They tend to think of such assets as being “safe.” While they may under many circumstances counter-balance the risks of stocks, they are not totally “safe.” They don’t protect from longevity risk or inflation. As we have seen, Social Security, annuities, and pensions (especially those that are adjusted for inflation) are “safer,” but there are some risks with them as well.

Most financial advisors will suggest that you consider withdrawing no more than 3 to 4 percent from savings per year to start, which is considered to be a “safe” withdrawal rate. Those percentages are based on widely referenced research first published back in 1998 that concluded, “If history is any guide for the future, then withdrawal rates of 3% and 4% are extremely unlike to exhaust any portfolio of stocks and bonds during any of the payout periods shown. In those cases, portfolio success seems close to being assured…”

Because the study was based on a retirement time horizon of only 25 years and several historical periods of strong market gains, new models have been developed. The Trinity Study was recently updated by one of my favorite professional retirement “experts,” Wade Pfau, who used a different modeling technique. He found that a somewhat conservative 50% stock/50% bond portfolio would not fail when a 4% or less withdrawal rate was used for any 30 year period during 1926 through 2010. Note that the analysis period included both the Great Depression and 2007-2008 market crashes.

It would seem that maintaining a balanced investment portfolio in the 50/50 stocks/bonds range is key to supporting a safe withdrawal rate of 4 percent or less. If you are too much more conservative than that, you could run out of money unless you have a substantial savings balance. Withdrawing a much higher percentage could result in similar problems.

On the other hand, if you are too aggressive with your portfolio (80 to 100 percent stocks), there is also a pretty good chance you’ll come up short unless you withdraw a much smaller percentage. You could sustain significant losses that you can’t recover from – it’s all a matter of timing.

I have historically had a balanced (60/40) portfolio, and I would characterize myself as “moderately conservative” when it comes to investing. One of the reasons that worked out okay for people like me is that bonds have done very well during the last few decades. But we are now in a prolonged period of low bond yields, and as yields slowly increase, bond values will decline – the outlook may not be nearly as good going forward. In the decades ahead, younger people may need to allocate more to stocks, including international companies, to get similar results.

Because I am getting closer to retirement, I am currently sitting closer to 35/50/15 (percentage of stocks, bonds, cash), which is obviously more tilted toward fixed income and cash. That’s because I have been concerned about high valuations in the stock markets and a possible major correction just as I am getting closer to retirement. I would rather not be 60 percent in stock funds and then take a 30 percent hit early in retirement, which would be an effective overall reduction of 18 percent (30 percent of 60 percent is 18 percent).

Even if stocks get real cheap and I buy more, which I may do now that we are in a “correction,” I don’t see my stock allocation going above 40 or 45 percent – that just happens to be what’s right for me. Plus, in retirement, I would prefer to have at least two years of expenses in cash so that I could weather a severe economic storm if necessary without having to sell any sinking assets. I am shooting for starting out with a sustainable withdrawal rate of at least 3.5 percent to supplement Social Security, increased each year for inflation.

Where are you?

If your required savings withdrawal rate is at or below the generally “safe” withdrawal rate of 4 percent (3.5 percent or lower would be better), then you could consider it “sustainable.” Simply make the withdrawals and add them to your “guaranteed” income sources to cover your essential living expenses.

If you decide to go with a higher rate, perhaps 5 percent or more, you may be okay for a while. You won’t see a huge impact on your portfolio for many years. But, ultimately, your withdrawal rate will be the primary determinate of how long your money will last. You may experience a “loaves and fishes” event at any time, but it would not be wise to presume on that.

If your combined income exceeds your essential living expenses, then you will have extra to spend on “discretionary” expenses such as extra giving, hobbies, travel, and entertainment, etc.

One advantage to having some discretionary margin is that you can cut back during years when your investments don’t do as well, perhaps helping to ensure the sustainability of your withdrawals in the future. In fact, many financial advisors are urging retirees to consider such “return-adjusted” withdrawal strategies instead of the more traditional “safe withdrawal rate” of a fixed percentage of 3 to 5 percent.

But what if your required rate is higher than the “sustainable” rate? In that case, you have some difficult decisions to make, but that doesn’t necessarily mean you can’t retire.

As we have seen, the big wildcard regarding your ability to retire is your withdrawal rate. That’s because it is a function of your lifestyle (expenses) divided by your savings (investment assets). If that ratio is 4 percent or less, you’re in pretty good shape.

If your withdrawal rate is somewhat high but not off the charts – say, in the 5 to 7 percent range – then you may be able to retire if you are prepared to live very frugally and take some other actions, or consider other options.

You have options

If the numbers aren’t falling into place, you have some important decisions to make. Fortunately, as the diagram shows, there are other things you can do to mitigate a shortfall in retirement income:

Work longer and save

By far, the best option for many people is simply to work longer and save more, if they are able. This option may not be the most desirable, but it can be the most effective. It can have more of a positive impact than you might think.

First, your Social Security benefits will be higher, for life. Second, your savings may increase (through additional contributions and more time to grow), which could increase your effective withdrawal rate in the future. Third, if you need it, you’ll have more time to pay off debt, which will decrease your essential living expenses.

A variation would be to work part-time in retirement to supplement your other income sources. Many retirees turn hobbies and other pursuits into “side gigs” that can generate a little income, and a little can go a long way when you’ve got a small shortfall. Plus work can be fun!

Annuitize some of your assets

Another alternative is to increase your sustainable income by annuitizing some of your retirement savings. That strategy would involve the purchase of an annuity so that your withdrawal rate is more viable for your lifetime.

An annuity may help address the problem because, typically, annuity payout rates tend to be a little higher than your sustainable withdrawal rate. However, that gap is narrower now than it’s been due to historically low-interest rates and longevity trends.

Whatever savings you put into the purchase of an annuity will give you more “bang for the buck” versus other “safe” investments and thereby bring your withdrawal rate closer to your sustainable rate. The other major factor is the fact that annuities are insurance contracts and are, therefore “guaranteed” by the companies that underwrite them.

How can annuities pay more than prevailing interest rates on “safe” investments such as CDs, savings accounts, short-term bonds, etc.? Mainly because some of the money is the return of principal, not just interest income. Plus, because annuities are funded via “risk pools,” the insurance company keeps the premiums of those who die early to make the payouts of those who live longer.

The cost for this wonderful magic is the price of your annuity. In most cases, you have to withdraw the money from savings, effectively removing it from your investment portfolio, and your estate, and hand it over to the insurance company.

I do want to point out that what I am mainly referencing here are Single-Premium-Immediate-Payout-Annuities (SPIAs). (See my earlier article on annuities to review the other types.) They tend to be easier to understand, less costly, and easy to purchase.

If you go this route, there are a few things to consider: First, do you need a survivorship clause (most couples will)? Second, do you want inflation protection (usually a good idea, but it will come at a cost)? And third, do you want to leave something to your estate (will require other special provisions, again, at a cost).The impact of any or all of these options can be a decreased payout.

Downsize or tap home equity

I consider tapping home equity via reverse mortgages to help fund retirement a last resort. However, downsizing to eliminate mortgage debt, or to put some equity to work generating income, can be a great way to deal with a shortfall.

For example, if you live in a $400,000 house but can get by with one for $200,000, then you could downsize and annuitize the other $200,000 to generate an additional $8,000/year in “guaranteed” income.

What if the numbers just don’t add up?

If you aren’t able to work any longer, and don’t have the options of annuitizing or downsizing, but still have a shortfall regarding covering your essential expenses, you may need some help. My suggestion is to discuss your situation with a pastor and your family honestly. Ask them to look at your finances to see if there is anything that can be done. You could also meet with a financial counselor or retirement planning professional.

If you are a faithful Christian with a family and part of a community of believers, you can ask them for help. As I wrote in an earlier article:

This suggestion won’t be very popular, but here goes: Get help and support from your children. I know that’s the last thing that anyone would want to do, but it is an option. Families should take care of each other. As parents, you scrimped and sacrificed for your kids. Perhaps you spent money you should have saved for retirement sending them to college or paying for an expensive wedding or helping with the down payment on a first house. Let them know you could use some help. That doesn’t mean moving in with them, but it might. At least get close to your family if you can – geographically and emotionally.

And of course, you can also pray and trust that God will provide for you as he has promised. He knows what’s going on in your life — that includes your checkbook and your savings accounts. He also knows what you will need exactly, all the time, and he wants to help you. Yes, it may be challenging, but no matter what, God doesn’t want you to succumb to fear and hopelessness.

May the God of hope fill you with all joy and peace in believing, so that by the power of the Holy Spirit you may abound in hope. Romans 15:13 (ESV)