In Investing for Retirement – Parts One and Two, I introduced a ‘framework’ for investing for retirement and discussed different asset types and holding options, and also active versus passive management styles. Once you make those decisions (or have some idea what you want to do), you’ll need to decide how you want to implement them. That is the focus of this post – the third in a three-part series on investing for retirement.

This decision is a very critical one that can have a big impact on your long-term success. Exactly how you achieve your goals will also be affected by your investing strategy (growth, income, growth and income, etc.).

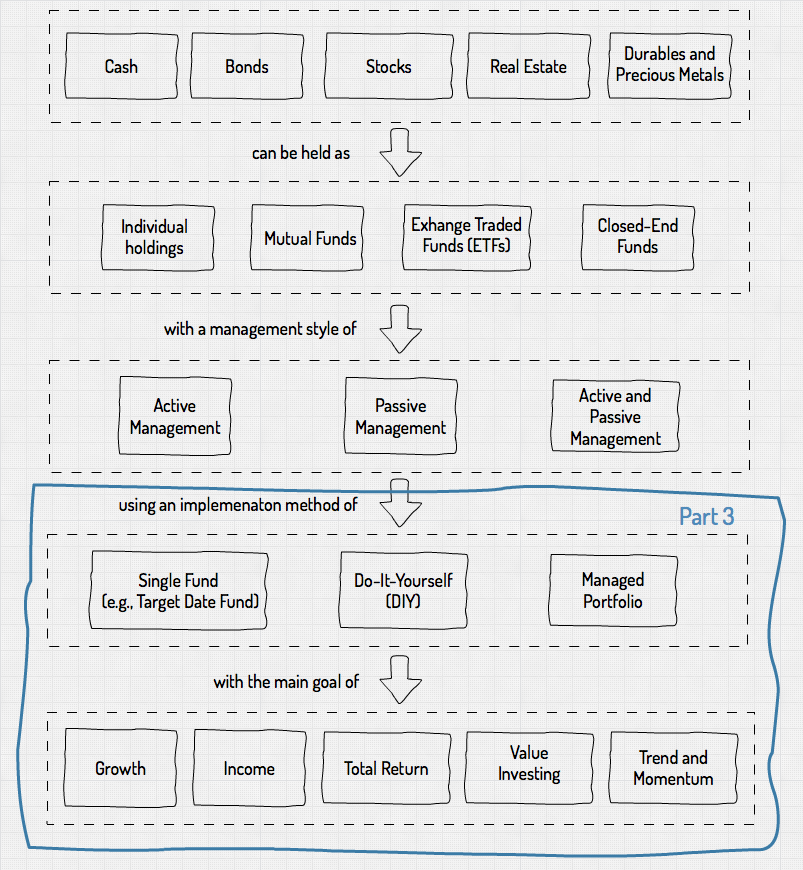

To help you keep your bearings, here is the investing framework I have been using, with the topics covered by this final article in this series highlighted:

Ways to implement your approach

You have several choices here. The main distinction is between doing it yourself (DIY) and hiring an investment advisor. Most people are, by default, do-it-yourselfers as they are choosing the investments in their 401/k or 403/b. They may or may not be doing so in an IRA. However, as we shall see, both have their advantages and drawbacks – the right option for you depends on your particular situation.

Managed portfolio

This is usually a portfolio containing a mix of different investments that are managed by a professional advisor based on your situation and risk tolerance, typically with a “total return” approach to growth (more on this later). Preferably, your portfolio manager is a financial professional who has a fiduciary responsibility to act in your best interest, but most importantly, someone that you have confidence in and trust.

You would more commonly use this approach in an IRA, but some employers offer “managed portfolios” as part of their 401/k offerings. The “portfolio manager” constructs the portfolio based on your age, risk tolerance, planned retirement date, investment objectives, etc. There are costs associated with this approach. An example of a “managed portfolio” is one offered by Fidelity Investments. The costs vary depending on the type of service you choose. That is a good option for someone who wants to rely on a financial professional to help them with their investment choices and make changes when conditions warrant.

Many portfolio managers subscribe to something called “Modern Portfolio Theory” (MPT). You can find a lot of sophisticated definitions about MPT. They’ll use phrases like “correlation index,” “efficient frontier,” and “variance and standard deviation.” But what it is really about is the relatively simple principle of optimal diversification that achieves the best results with the lowest possible risk. Moreover, to further simplify – not putting all your eggs in the same basket.

So, MPT has mainly to do with using the right mix of asset types in your portfolio so that you maximize your returns while minimizing risk. You “diversify” across different asset types such that, under certain economic circumstances, one may go up when the other goes down and vice-versa.

Just the other day, I was talking to my wife about the stock market. (Yes, she is interested in it, at least to the extent that she likes to know how our savings are doing.) It was one of those days when the markets were down close to 2 percent. She had been listening to the news, and of course, they were talking about it with the usual hype. I showed her our IRA account online at Fidelity in which all of the stock funds were down, but several other investments (mainly fixed income funds and a gold fund) were up. (That isn’t always the case – I have seen them all red and also all green.)

Sometimes, when one type of asset (e.g., stocks) are down, others (e.g., bond) will be up. Depending on the factors that are causing the volatility, even though an asset class may be quite volatile at any given time, it tends to make the volatility of the entire portfolio less overall.

I like this approach. I use a variation of it myself, as evidenced by the little interchange with my wife I described above. I am probably not as diversified as most MPT portfolios, which may hold 10 or 15 different asset classes, but I am using the principle. I simply have a mix of stocks (domestic and international), bonds (short and long-term), and alternatives (preferred stock and gold), as well as a fairly large cash holding. (If you want to read more about MPT and get help to build a portfolio based on MPT methods, I recommend 7Twelve: A Diversified Portfolio with a Plan.)

Also, if you decide you want to go the managed-portfolio route, there are many ways to implement it. I discussed most of them in this article.

Do-It-Yourself (DIY)

With this approach, you take responsibility for building your portfolio, so it can be almost anything you like. You can use this approach in either a 401/k or IRA, but with the former, you may have a limited number of investment options. If your company plan offers a self-directed brokerage account option, then you will have much more flexibility. Typically you’re going to shoot for a well-diversified mix of investments with a goal to maximize “total return,” but it may be tilted more toward growth or income depending on your age and risk tolerance.

For example, I manage my own IRA. Because of my current age and proximity to retirement, I have become more conservative and orient my investments more toward income than growth. I have a higher percentage of my investments in bond funds (close to 60 percent) than stocks (less than 40 percent), and the stock funds I own have a focus on generating income through dividends.

The costs for the DIY option are usually lower than a managed portfolio, but you will still have to pay the management fees for the investments you choose. You can implement this for an IRA account at Vanguard, Schwab, and Fidelity and other brokerages.

Single fund approach

This approach is usually a variation of the DIY model discussed above. It is the height of simplicity, and you would typically use a “Target Date Retirement Fund” to implement it. You could use this in your 401/k (if available), your IRA, or both. With this approach, you purchase a single fund based on your age and desired retirement date. The fund automatically adjusts its asset allocation (mostly stocks and bonds) as you age – from more to less “aggressive” regarding the percentage allocated to stocks. The main cost of this approach is the management fee for the fund, which is relatively low in most cases. A good example is the Vanguard Target Retirement 2045 Fund (VTIVX). It charges a fee of only 0.15%. This fund can be an excellent choice for someone who is looking for an effortless but effective option.

I have heard some suggest that you can build an entire portfolio with just one or two funds. That’s certainly true in the case of target-date and other lifestyle funds. However, you could also use a total stock market fund like the Vanguard Total Stock Market Index Fund (VTSMX) or the Fidelity Total Market Index Fund (FSTMX). With either of your funds, you would capture total stock market offers you. If you wanted to add bonds to the fund, you could add a total bond fund such as VBMFX or FTBFX.

Which is best?

That’s a hard question to answer. As I have written before, most people would do well to use a financial advisor, preferably one who has no conflict of interest. I recently wrote a series of articles about financial advisors and how to choose one. The most significant advantage in using a trusted advisor is not so much in the investments they choose; it’s what they do to help you keep a steady hand on the wheel, especially when things get tough.

If you’re comfortable doing it yourself, and you think you can stick to your strategy during thick and thin, you may make out better in the long run. That’s because advisor fees can add up – and remember, they’re in addition to whatever fees you’re paying for the investments themselves.

If you’re interested in going the DIY route, I would strongly suggest taking the time to educate yourself. You don’t have to be a CPA or a CFP to do it, but you do need some basic knowledge, wisdom, and discipline. To that end, there are many good books and blogs on investing that provide excellent ideas on asset allocation plans. I have listed several on the Resources page of this blog. If you’re a “beginner”, consider: Sound Mind Investing Handbook (by Austin Pryor), The Bogleheads Guide to Investing (by the Bogleheads), The Little Book of Common Sense Investing (by John C. Bogle), The Little Book of Bulletproof Investing (by Ben Stein & Phil DeMuth), and Investing Made Simple (by Mike Piper, CPA). To go more in-depth, look at Unconventional Success: A Fundamental Approach to Personal Investment (by David F. Swensen), A Wealth of Common Sense (by Ben Carlson), and Financial Fitness Forever (by Paul Merriman & Richard Buck).

Your investing goal

Regardless of which approach you decide on, you’ll need to come up with a basic investing strategy. Will you invest for growth, income, or total return? Since you are investing for retirement, we are mainly concerned with how specific investment types contribute to increasing the value of your portfolio over time. You can use these different investment strategies in both 401/k and IRA accounts – your focus could be on growth, income, or both (also known as “total return”). Let’s take a closer look at each of these:

Growth investing

For most people in the accumulation stage, the main objective is growth over the long term, but without taking more risk than you are comfortable with. The most common investments are growth stocks that grow earnings faster than others, which translates into a growth in share price (a.k.a., “capital gains”). Because most “growth companies” are retaining their earnings and reinvesting them in the company, they don’t typically pay dividends to shareholders.

You can invest in growth stocks by picking them yourself or in consultation with your broker or advisor who would buy them for you (for a commission, of course). An alternative is to let your broker/advisor select them for you without your direct involvement. Both of these approaches can be riskier if neither of you has deep expertise nor experience in this area.

This is why many people opt for growth-oriented mutual funds. Such funds contain many different growth stocks that are picked by the fund’s asset managers. You (or your broker/advisor) choose the funds (instead of the stocks) that have a good chance of increasing in value.

An excellent example of a growth company fund is one that I once owned in my IRA: the Fidelity Growth Company Fund (FDGRX). (It is currently closed to new investors.) The investment “policy” of this fund on Fidelity’s website is:

The Fund seeks capital appreciation. Fidelity normally invests the Fund’s assets primarily in common stocks. Fidelity invests the Fund’s holdings in companies Fidelity believes have above-average growth potential.

Notice that the policy statement could be the definition of almost any growth-oriented stock mutual fund.

Another good example is the iShares Russell Growth 1000 ETF (IWF). It is comprised of over 500 stocks that track the Russell 1000 Growth index, which measures the performance of large- and medium-size companies that are expected to grow earnings faster than the broader market.

There are many others out there – look for consistent performance and low cost when choosing one.

Value investing

A variation of stock picking is to focus on “value” stocks. It is the strategy espoused these days by famous investor Warren Buffet. It involves choosing undervalued stocks based on a detailed analysis of the company’s fundamentals, such as income and balance statements, management, competition, markets, etc.

The success of this approach is to buy stocks when they are “on sale”; i.e., at a price that is less than what it is really worth. Theoretically, there is less risk in such a purchase, combined with a greater probability that it will out-perform growth stocks over the long term. Many “value” stocks also pay dividends, which helps to provide a margin of safety.

Some studies have shown that value stocks do better than growth stocks over the long term. The challenge is in finding them. You can buy individual value stocks, but you have to do your homework. Fortunately, there are also plenty of value stock mutual funds and ETFs, which you can use instead of individual stocks.

An excellent example of a value stock fund that I have previously owned in my IRA is the Fidelity Low-Priced Stock Fund (FLPSX). According to Fidelity, the objective is capital appreciation by,

Normally investing at least 80% of assets in low-priced stocks (those priced at or below $35 per share or with an earnings yield at or above the median for the Russell 2000 Index), which can lead to investments in small and medium-sized companies.

A good example of a value-stock-oriented ETF is the iShares Large-Cap Value ETF (JKF) which invests in “large U.S. companies that are thought to be undervalued by the market relative to comparable companies.”

Some value stocks pay income. For example, the iShares JKF fund is currently yielding 2.43%, which is pretty good. However, to see a significant increase in share price, you may need to hold on to the fund for a pretty long time.

Income investing

Income investing is just as it sounds – investing in assets whose primary objective is generating income. Income-generating assets can be stocks, bonds, or real estate. While they may offer some opportunity for growth, their primary focus is current income.

One top-rated fund is the Vanguard Wellesley Income Fund that I listed above. Vanguard’s website describes the fund as an “income-oriented balanced fund [that] offers exposure to stocks and investment-grade bonds.”

Another excellent example of a stock fund is one that I currently own in my IRA: the ProShares S&P 500 Dividend Aristocrats EFT (NOBL). The fund targets results consistent with the S&P 500 Dividend Aristocrats Index. It currently yields dividends of 1.88%. Another is one that I have owned for several years in my own IRA: the Schwab US Dividend Equity EFT (SCHD). US News and World Report…

Schwab US Dividend Equity ETF is … a low-cost portfolio of profitable stocks with attractive dividend yields. SCHD is part of Morningstar’s large-value category, referring to funds and ETFs generally holding large-cap U.S. stocks that are less expensive or growing more slowly than other large-cap stocks … the fund tracks the performance of the Dow Jones U.S. Dividend 100 Index, which selects from the 2,500 largest U.S. stocks that meet a number of criteria, including 10 consecutive years of dividend payments. It owns shares of 103 companies meeting the benchmark’s screening criteria.

Many income-generating funds hold bonds instead of stocks. Because bonds represent loans to companies, the interest paid is returned to fund holders as income. A good example of a fund that I also currently own is the iShares 0-5 Year Investment Grade Corporate Bond ETF (SLQD). The iShares website describes it as a fund that,

… seeks to track the investment results of an index composed of U.S. dollar-denominated, investment-grade corporate bonds with remaining maturities of less than five years.

Because the bonds it holds are of shorter duration, the income is currently at about 3%.

Neither of the two funds I have listed is likely to experience rapid growth in their share price. But that’s not why I own them. I am holding them as more conservative investments that will generate some of the income I will need to live on in retirement.

Investing for total return

Total return is probably the most popular approach to investing for retirement. Total return describes a way of investing that seeks to maximize the performance of an investment or a pool of investments through growth (capital gains), interest, dividends, and distributions over time. In other words, it’s not focused on growth or income specifically but seeks to achieve both.

Investing for total return is a mainstream strategy that can be easily implemented by investing in just a handful of low-cost mutual funds or ETFs that cover the growth, value, and income spectrums. Many implement this strategy by choosing index funds to capture the gains of the market index represented by the fund. An example of a fund that I have in my IRA to capture the overseas developed markets is the iShares Edge MSCI Min Vol EAFE ETF (EFAV). This fund “seeks to track the investment results of an index composed of developed market equities that, in the aggregate, have lower volatility characteristics relative to the broader developed equity markets, excluding the U.S. and Canada.” EFAV pays a dividend of 2.46% and has a 5-year total return of 9.42% (21.57% over the last year). It has a slightly more volatile cousin, the iShares Core MSCI EAFE ETF (IEFA).

A good example of a mutual fund is the Vanguard 500 Index Fund Investor Shares (VFINX). According to Vanguard, it is “… offers exposure to 500 of the largest U.S. companies, which span many different industries and account for about three-fourths of the U.S. stock market’s value.” It currently pays a dividend of 1.83% and has had a 5-year total return of 13.14% (13.84% over the last year).

This approach is also known as “passive index investing,” which I discussed earlier – and it is becoming very popular. It has been my strategy for the last decade or so, although my investments are now tilted more toward the income side of things. It is relatively easy to set up and requires the least amount of time and expertise to manage. If done right, a total-return portfolio will have a moderate risk, which is best for investors during the accumulation phase, in my opinion.

Consider the “simple” index-fund based portfolio constructed by Tim Maurer and detailed in his excellent book, Simple Money: A No-Nonsense Guide to Personal Finance. If you take a look, you’ll see that it includes both growth and income stocks – that’s the “total return” part.

A possible shortcoming of this strategy is that you may not receive a consistent income. The total return means that you are achieving your investment goals via both growth and income. That may mean that you can live off the income generated by the portfolio alone – you may need to liquidate shares in order to produce the income you need. Another challenge is that a volatile stock market may have a greater impact on your portfolio. That can be mitigated to some extent by holding some bonds or bond funds, if (and this is a big if) they move in an opposite direction from stocks. A big positive for this strategy is that is simple and easy to manage – this is something that gives the average investor their best opportunity for success.

Trend and Momentum Investing

This strategy is more tactical (short-term, as compared to value investing, which is more long-term) and is focused on understanding and benefiting from certain market trends and the likelihood that they will continue in the future. It requires more technical analysis and views market trends link light of both macro and microeconomics as well as investor sentiment and emotion. As such, it can be riskier, but if the trends are rightly understood and play out as anticipated, it can produce higher returns in the short-run.

I don’t do momentum trading nor do I own any momentum-following investments. If you are interested in this strategy, check out the momentum strategy that is used by Sound Mind Investing. You can also learn more about momentum trading strategies in this article by Fidelity Investments.

Which approach is best?

Once again, there is no “one size fits all” answer here. Most younger workers who are saving for retirement concentrate on growth or total return. Those who want to be more tactical and hands-on may tend toward trend and momentum following. Generally speaking, I tend to favor the total return approach using a well-diversified portfolio of mostly passively-managed index funds. However, as I noted in the last article, I use actively-managed funds where I think they make sense.

Older folks who are nearing or in retirement may favor income-oriented investments, for obvious reasons. Growth is less of a concern – the need is to preserve capital and generate the income you need to live on in retirement. I plan to do a couple of articles very soon about investing in retirement, so stay tuned for that!

Don’t obsess

I have presented a lot of material in this series on investing for retirement. I know it’s a lot to take in (it is for me too). But the reality is that I have only touched the surface in some areas. You may want to do more reading and study on the subject, but if there is one piece of advice I would give you it would be this: Don’t obsess over having the absolute best investments – it’s more important to live below your means and save regularly. If you decide on a basic approach using a few proven funds, diversify, and mostly just leave it alone, you’ll have a pretty good shot at having enough when you decide to retire.