In a recent article, I discussed spending in retirement and whether our costs go down as we age. In this article and the next, we’ll look at the other side of the equation: generating income, specifically the different ways to withdraw from savings to fund your spending, hopefully for as long as you live.

This is part of wise retirement stewardship. Wisely managing the resources God has entrusted to us to take care of ourselves and our families, and if possible, with a surplus for generous giving. It’s not about achieving absolute safety and security by coming up with a failsafe plan; there’s no such thing. We do what we can while placing our ultimate faith and hope in God’s providential care and provision for us.

There are two big questions to answer when planning for retirement: 1) How much is enough? and 2) Once you have “enough,” how can you generate enough income to live on while ensuring you don’t run out of money too soon? Question number one is about accumulation, and question number two is about decumulation.

Both are challenging but closely related questions to answer if for no other reason than how much is enough depends on how much you will spend and how quickly you spend it. But this article will be concerned primarily with question number two. And it’s a crucial question for those who need to rely on their retirement savings for a portion of the income they need in retirement for as long as they live.

Strategies and more strategies

Most retirees will need some kind of income-generating strategy, especially those with relatively small portfolios. Even if it’s “spend what I want until it’s gone and then hope for the best” (a fun approach while it lasts), everyone will have a plan. And some are better suited to your situation than others.

However, the sheer volume of funding strategies available to someone planning retirement can be overwhelming. There are systematic withdrawal rates, floor-and-upside, bucket strategies, dividend strategies, cash reserve strategies, and then there’s the strategy economists love and consumers hate, purchasing life income annuities.

No one says you have to limit yourself to one strategy, so you can combine these and others to create a hybrid approach to fit your specific financial situation.

Boiling them down

Not to over-simplify, but most retirees’ strategies will include income from one or both of the following sources:

- Withdrawals from a risk-based investment portfolio (stocks, bonds, etc.)

- Income from “guaranteed” sources such as pensions, Social Security, annuities, or whole life insurance (some may also include reverse mortgages).

Assuming that the majority of retirees will have Social Security benefits and some amount of invested assets at a minimum, the fundamental question is this: “Will my ‘safe’ income sources (e.g., Social Security, annuity, etc.) along with income from a ‘risk-based’ portfolio provide enough income to support my spending needs for as long as I (and perhaps a spouse) live?

The answer to this question hinges on how much ‘safe’ income you have and the long-term sustainability of your income withdrawals from your portfolio. This article is focused on the latter: income withdrawals and the most popular strategies for making them.

The most common approach is some type of “systematic withdrawal strategy” that can be further broken down into two sub-strategies: Taking fixed withdrawals as an annual percentage or a specific amount (perhaps with yearly adjustments for inflation) is the simplest, and variable withdrawals based on year-to-year portfolio performance or other factors, which can be more complicated. We’ll look at the former in this article and delve into the latter in the next.

Fixed withdrawal strategies

The fixed withdrawal can be an amount or a percentage of your portfolio’s value, with the withdrawal amount adjusted annually for inflation. It’s still considered a “fixed” withdrawal even though the amount will grow over time as it remains constant in real (inflation-adjusted) terms. In other words, your spending power remains constant.

At the center of the fixed withdrawals strategy is the revered 4% “safe withdrawal rate,” proposed by Willian P. Bengen in 1994 and confirmed by the well-known “Trinity Study” a few years later. The study used a model that showed a 95%-98% probability that you wouldn’t run out of money if you start retirement by withdrawing an amount equal to 4% of your portfolio’s value, annually adjusted for inflation (so not exactly an equal amount from year to year).

Later studies based on the same set of assumptions produced similar results. That led to institutionalizing the “4% rule” in the retirement planning industry.

To illustrate: if you own a $400,000 portfolio, you would withdraw $16,000 a year (.04 x $400,000 = $16,000.) If inflation were 2.5% in the first year, you’d take out $16,400 the next ($16,000 x 1.025 = $16,400). A 3% inflation rate in year two would mean withdrawing $16,892 ($16,400 x 1.03 = $16,892) starting in year three. You stay the course irrespective of the value of your assets, which would fluctuate based on market conditions.

Perhaps you see some problems with this strategy, especially the “irrespective of your assets’ value” part. Withdrawing an increasing percentage from depreciated assets will accelerate their depletion. As the old proverb says, “If you fall into the hole, stop digging.”

Over the last twenty years, during historically low-interest rates, many retirement professionals understandably questioned this strategy. They concluded that setting a fixed withdrawal rate with an annual adjustment for inflation and sticking to it for your entire retirement was no longer realistic. Not to mention that no rule of thumb can account for all the real-world variables retirees may have to deal with.

Some recommended a lower initial portfolio withdrawal rate of 3% to 3.5% for a similar probability of success (i.e., a 95% chance of a portfolio lasting 30 years or more). There were also concerns that many retirees would not be willing to hold at least 50% in stocks throughout their retirement, which was the allocation used in the original studies.

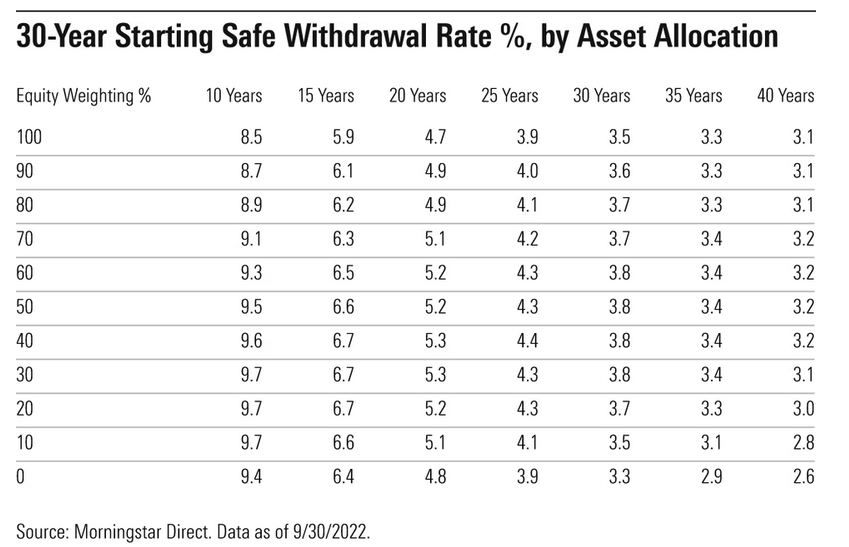

More recent studies have adjusted the rates a little higher. For example, a recent report from Morningstar titled “The State of Retirement Income 2022,” citing higher interest rates, put the “safe” starting withdrawal percentage at 3.8%, with annual inflation adjustments to withdrawals after that.

Interestingly, concerning asset allocation and the safe withdrawal rate, the study found that,

While with our base case we concluded that a 50% stock/50% bond portfolio was likely to sustain itself over a 30-year time horizon with a 3.8% starting withdrawal, we found that a retiree could dial equity exposure all the way down to 30% and still employ that same starting withdrawal percentage of 3.8%.

Here’s a table from that study. To use it, find your equity allocation percentage in the far left (mine is 40%) and how long you need for your savings to last on the top row (I’m using 25 years), and you can get your “safe” withdrawal rate percentage (for me, that’s 4.4%, which is less than I’m currently withdrawing).

Other studies have come up with rates that are both higher and lower. That said, a reasonable estimate would be a range of 3% and 4%, depending on total assets, risk of depletion, and whether you’d like something left for heirs.

The risks

The most common investment strategy associated with fixed withdrawal is often called a “total return strategy.” Essentially, it seeks a stock/bond allocation on the “efficient frontier” that aligns with a retiree’s risk tolerance, aiming for the highest possible portfolio return considering the level of volatility (risk).

For many retirees, a stock allocation of around 40% to 50% would be suitable; others will want to be more conservative. Those using the total return approach typically reinvest dividends and interest to contribute to growth and regularly sell assets (e.g., fund shares) to generate income.

You (or an investment manager if you have one) retain control over your investment capital, and there is a possibility that your investment results will be favorable enough to maintain your fixed withdrawals and perhaps increase them in the future.

The risk of withdrawing from a risk-based investment portfolio is that growth and income are unpredictable (duh!). We know how easy it is to lose money in stocks, even the “safer,” low-volatility ones. We also know that bonds, including treasuries, carry interest rate risk (as many of us know based on how bonds performed in 2022). When rates rise, bonds lose money. Bond prices may go up when rates go down, but yields (those all-important monthly interest payments) to investors go down.

The lower your savings, the less you can withdraw from them to increase the probability they will last. But smaller withdrawals mean less income. Withdraw too much, or experience significant investment losses early on, and you risk running out of money. Withdraw too little, and you may be unable to pay the bills.

Is this strategy for you?

Retirees with a savings surplus will be the most comfortable with this strategy as the likelihood of running out of money if they start with a relatively low withdrawal amount and experience average annual returns that at least keep up with inflation is pretty low.

Those with small balances comfortable with a 5% to 10% probability of depleting their retirement funds might also choose this strategy. It will also appeal to those comfortable with withdrawing from a diversified stock/bond investment portfolio and believe in the stock market’s ability to rebound over time and remain unfazed by significant fluctuations in their account’s value.

Moreover, this strategy is suitable for those who don’t require a guaranteed and consistent annual income or a safety net to prevent a drop in spending. It may be particularly ideal for individuals whose income floor is adequately covered by sources such as Social Security retirement benefits and other pensions.

But wait, there’s more

As we’ve seen, fixed withdrawal strategies are popular and certainly have their place. But they’re not for everybody, especially those with less savings. My next article will look at variable strategies, which may make more sense for many people.

Coming up with the right withdrawal plan is very important. Given all the uncertainties, precision is scarce. We’re not shooting for certainty but reasonable sustainability. So consider the options carefully, perhaps with the help of a trusted advisor who’s an expert on retirement income planning.