This article is the second about the incoming Biden administration and its plans and proposals that could be most impactful to those planning for or already in retirement.

I wrote these articles because part of wise retirement stewardship involves understanding the changing “times and seasons.” As Dan. 2:21 says,

He changes times and seasons; he removes kings and sets up kings; he gives wisdom to the wise and knowledge to those who have understanding;

The presidential election is still being contested, and the Georgia U.S. Senate election will determine whether the Republicans will maintain a small majority in the U.S. Senate. (It’s underway as I finalize this article for posting.)

As I noted in the previous article, if the Republicans retain control, any significant changes to the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) of 2017 and certain other legislative proposals will be challenging for the Biden administration to push through.

In the last article, we looked at healthcare, Medicare, and income taxes. In this one, we’ll examine public and private retirement programs: Social Security and retirement savings accounts (IRAs, 401(k)s, etc.).

As in the last article, I won’t opine on these proposals’ political aspects or guiding ideologies; I will take a more pragmatic, “Will it work?” “Will it help?” perspective. (But I may slip an opinion or observation in here or there.)

One thing is sure: Social Security, Medicare, and health care need “attention,” regardless of who is in control of Congress. That’s not the core of the debate; it’s how to address them that divide the political parties.

Social Security

Biden basically wants to keep most aspects of Social Security the same and generally shore-up the program. But there are some proposed changes, which include expanding and increasing the benefits for many recipients. Here is a summary of the major proposals:

- Continue funding of Social Security through the current trust fund structure.

- Trust fund investments in government bonds rather than private investment options.

- Benefits available to all who qualify without means-testing.

- Increase benefits for those who’ve been retired for 20 years or longer.

- Raise the minimum benefit for lifelong, low-income workers.

- Prevent surviving spouses from big cuts in their total benefits after the death of a spouse.

- Do away with provisions that reduce or eliminate benefits for some who also receive public-sector pension benefits.

All in all, this is the status quo, along with efforts to expand the program for some recipients in exchange for higher payroll taxes for others.

One objection to the plan is that it alters Social Security’s original concept of “shared worker funding,” whereby current workers’ payments, up to a certain income level, pay for current benefit recipients’ benefits. Sustainability was possible because there have been more workers than recipients.

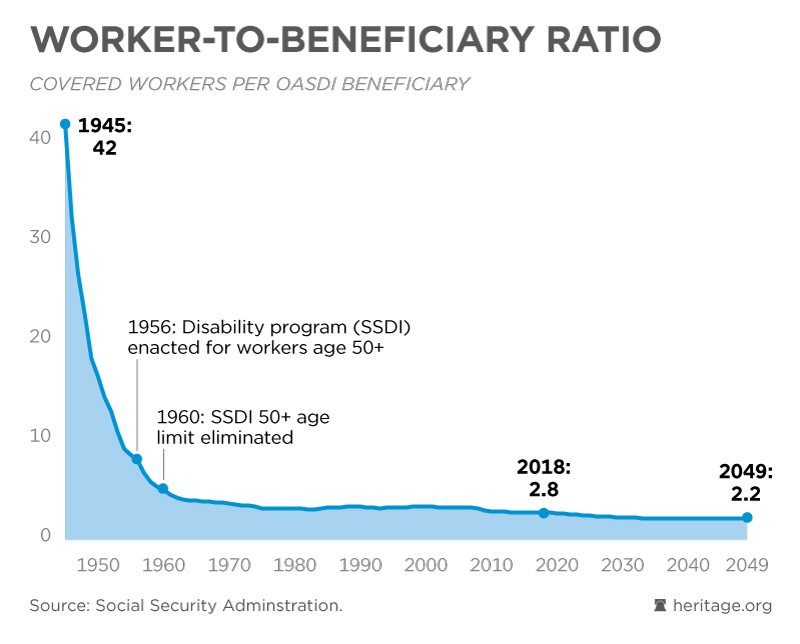

The problem is that the ratio of workers (contributors) to recipients (non-contributors) has decreased.

According to data from the Social Security Administration and the Heritage Foundation, as illustrated in the graphic below, the problem is that the ratio of current workers to recipients had gone from 5.1 in 1960 to its lowest ever; 2.8 in 2018, and it’s estimated to be 2.2 by 2049. (The Social Security Trust fund was “stable” at about three workers to one recipient.)

The changing demographics mean that the additional revenues needed to fund the program at increased and expanded levels have to come from elsewhere.

Under the Biden plan, high-income earners would have to pay more tax in return for no additional earned benefits. Biden’s plan would increase the payroll taxes on those with higher incomes to fund expanded and larger benefits for others. (This coincides with his proposed increase in the highest marginal tax rate for corporations and individuals earning $400,000 or more a year.)

The logic, I suppose, is that those with higher incomes shouldn’t need those additional benefits. And, it would make up for the lower contributions from lower-income workers. The claim is that despite the many challenges Social Security already faces and the additional cost of these expanded benefits, increasing the tax will assure the program’s long-term solvency.

The Federal Income Tax system is a “progressive” one. That means that those in higher income brackets pay a larger percentage of tax. Social Security payroll (FICA) and self-employment (SECA) taxes are just the opposite. Workers pay 6.2% (their employers pay the other 6.2%), regardless of their income. (The self-employed and business owners have to pay the full 12.4% SECA tax.) However, those making more than $137,700 in 2021 don’t have to pay the tax on any amount above that.

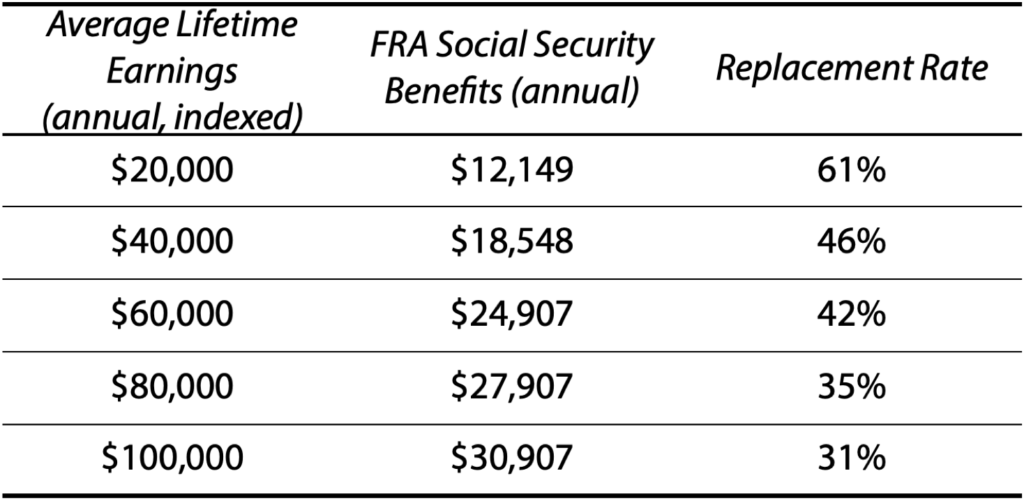

On the other hand, the benefits from Social Security are progressive. The lower one’s income over their lifetime, the greater the benefit they’ll receive from Social Security on a relative basis. Take a look at this graphic based on data from Social Security:

As you can see, someone making $20,000 may have 61% of their pre-retirement income replaced by Social Security, whereas someone making $100,000 will have 31%, which is 50% less. The benefit is “progressive” for those who earn and therefore contribute less over their lifetimes.

Biden wants to make the program more progressive than it is by raising the payroll tax cap. There has also been some discussion about making the benefit calculation formula itself even more progressive.

Those who are not in favor of a more progressive approach may have some legitimate questions, such as:

- Why shouldn’t every worker participate in some way to make the program sustainable?

- Why shouldn’t every worker receive some additional benefit based on increased contributions, even if it’s not proportional?

On the one hand, I think it’s good that Biden is thinking about changes that need to be made to make the program solvent. But I’m not sure that asking less than 2% of wage earners to shoulder the entire burden is entirely fair. And even if it is, it may not automatically put Social Security on an indefinitely sustainable course as it doesn’t solve the worker to benefit recipient ratio problem.

The Social Security Trust is running out of money (and this has accelerated due to the economic fallout from the pandemic, including the suspension of payroll taxes in 2020), and there are many questions about whether just raising taxes and then spending the additional revenue on additional benefits would actually make the program sustainable long-term.

Retirement Plans

The Biden Plan includes additional incentives for people to plan and save more for retirement.

- Equalize the tax benefit incentives of defined contribution plans for middle-class workers.

- Remove penalties for caregivers who want to save for retirement.

- Give small businesses a tax break to start a retirement plan and give workers the chance to save at work.

- Worker access to “automatic” 401(k)s if not available at work.

Tax Incentives for Saving

If you are a regular reader of this blog (and others about retirement), you know that a good retirement plan starts with years of diligent saving. But, despite the increasing availability of employer-sponsored programs and existing tax incentives, Americans are terrible at saving for retirement. (According to the Federal Reserve, the median savings for those aged 50 to 60 are less than $50,000!)

The Biden Plan wants to change this by providing more incentives to help low- and middle-income earners save more. It will do this by equalizing the tax savings benefits across the income scale so that these workers get a larger tax break when they save.

The current tax benefit for saving in defined contribution plans (401Ks, IRAs, etc.) is based on the concept of tax deferral. Savers get to exclude their contributions to these accounts from taxes, their savings grow tax-free, but they have to pay taxes on the money when they withdraw it in retirement. The Biden team asserts that this system favors those in the upper-income brackets as they get a much better tax break while providing little or no benefit to lower- and middle-class workers with fewer earnings.

Based on current tax rates, the highest earners can get a much as a 37 percent tax benefit from their retirement plan contributions. (That’s because they are in the 37 percent marginal tax bracket.) Such a person who contributes the maximum of $19,500 can get a tax savings of $7,215. But a lower earner who is in the 10 percent bracket receives a $1,950 benefit. (Of course, whether they could, or would, contribute the maximum when making a middle-class salary is debatable.)

Here’s how the Biden Plan would work: Instead of an up-front tax deduction, Biden’s plan would give everyone a percentage tax credit based on how much they contribute. The projection (exact amounts aren’t yet fully detailed) is that the credit would be about 26% of a worker’s contribution. For example, if a low earner contributes $5,000, they would receive a tax credit of $1,300, effectively reducing taxes dollar-for-dollar rather than just reducing taxable income. The high-income earner, who contributes $10,000, would receive $2,600, a higher amount but the exact percentage as the low earner.

The idea is that the low-income earner, who receives a marginal benefit from a tax deduction, will receive a much greater benefit from a dollar-for-dollar tax credit up to some percentage. The higher income earner will also benefit, but it won’t be as great as their tax savings if they are in the highest marginal tax brackets. (At a 26% credit, that largest amount a worker under age 50 could receive is $5,070, based on a maximum contribution. Compare that to a tax savings of $7,215 if they’re in the 37% marginal tax bracket.)

I’m generally a big fan of tax incentives that encourage people to save more. But I am also a realist; I know that some people won’t save no matter how great the incentives are. And getting people to save, to pay some attention to how they invest, and to adjust their spending if they need to save more, will always be a challenge. Will a greater incentive help? Perhaps.

On its face, the proposal kinda “feels right.” Low- and middle-income earners have a tough time. It’s hard enough to pay the bills, much less save $5,000 or more a year for retirement. Giving them a tax credit seems like a reasonable thing to do. But, as with every benefit increase, someone has to pay. In this case, it’s 20% or so of workers who pay the most in taxes already. (Although they also receive higher tax benefits under the current tax structure.)

It may also be helpful to think about how tax credits work. Typically, a taxpayer realizes a tax credit at the time taxes are filed; it reduces their taxes owed dollar-for-dollar. Suppose that’s the kind of credit envisioned here. In that case, the intended goal of encouraging lower- and middle-income workers to save more is defeated because it won’t immediately put money in their pocket to save if they have already had the money withheld for taxes. If they receive the credit as a tax refund, it becomes discretionary funds they can put toward more urgent needs (or wants), which may also be self-defeating.

Interestingly, there’s already a retirement saver’s credit, which many people apparently don’t know about. Known as the “Savers Credit” (formerly known as the Retirement Savings Contribution Credit), it gives a special credit to low- and moderate-income taxpayers who save for retirement. Of note is that this credit is in addition to current tax benefits for saving in a retirement account.

The credit is based on a worker’s adjusted gross income (AGI) and tax filing status. They can claim a credit of between 10% and 50% of the first $2,000 they contribute during a tax year to a retirement account. The maximum credit amounts that can be received are $1,000, $400, or $200. (Couples filing joint returns can get as much as a $2,000 credit.) The Savers Credit is a “non-refundable” tax credit. That means the credit can reduce the tax you owe to zero, but it can’t provide you with a tax refund.

We also have to remember that everyone who pays taxes gets a tax break if they contributed to a tax-deferred retirement plan. And these tax breaks are limited by law for higher-income earners (the most they can get is 37% of the maximum contribution of $19,500 in a 401K and $6,000 in a traditional IRA).

I am a retiree who is drawing from a traditional (taxable) IRA account. My savings plus Social Security are such that I can “afford” to pay the taxes (I include them in my “budget”), even though I don’t particularly enjoy it. But for those with fewer savings and smaller Social Security benefits, perhaps the government could make the distributions in retirement tax-free up to a certain income limit, say $40,000 a year. That would let some retirees keep more money in their pocket.

Help for Caregivers

The Biden Plan would also remove current penalties for caregivers who want to save for retirement. Under the current law, people who work as caregivers (for sick or aging relatives) without pay are ineligible for tax breaks for retirement savings. The plan would also allow caregivers to make “catch-up” contributions to retirement accounts, even if they’re not earning income.

That all sounds pretty reasonable to me; it’s compassionate towards those helping others and benefits those receiving care. But a logical question might be, “How can they save for retirement if they aren’t receiving any income?” Many caregivers have to leave the workplace to care for family members. When they do, they are no longer contributing to an employer plan. However, they could still contribute to an IRA. But they need money to contribute.

The exception would be where they are doing both (part-time caregiver and part-time employee). The latter may be in a better position to save something for retirement. To help, the Biden Plan would offer a $5,000 tax credit for “informal” caregivers. That would effectively be a tax subsidy for caregivers who are not working who and don’t contribute to a retirement savings account. If the caregiver receives the credit as a tax refund, it’s unclear if it would be mandatory for the caregiver to use it as a retirement account contribution. If that’s not the case, it may defeat the whole purpose, except to the extent that it is “free” income.

Tax Incentives for Small Business Retirement Plans

Another proposal that sounds interesting is to give small businesses a tax break for starting a retirement plan and giving workers the chance to save at work. The Obama-Biden Administration originally proposed this to encourage more widespread adoption of workplace savings plans, with tax credits to small businesses to offset some of the costs.

As with some of the other proposals, this one would cost taxpayer dollars. Where will those dollars come from?

Automatic 401(k)

Finally, under Biden’s plan, almost all workers without a pension or 401(k)-type plan will have access to an “automatic 401(k),” which they say would make it eaiser to save for retirement at work.

But this is a bit of a misnomer; it’s not actually “saving at work.” Under current state-mandated plans, employers forward a given percentage of the employee’s wages to an IRA managed by a custodian chosen by the state. There may be a federal (instead of an employer) match under the program, and the tax-deferral contribution provision would be eliminated in return. Whether this would work, especially since the pre-tax savings structure is removed, is a matter of conjecture. Plus, some employers currently providing retirement plans may simply decide it’s not worth their while and instead choose just to meet the legal requirements for payroll deductions for the federally mandated account system.

Will they work? Will they help?

I am not sure whether these provisions, which seem to have some good intentions in terms of helping lower- and middle-income workers, would actually have the intended results. Plus, they will cost taxpayers a lot of money. Therefore, the usual question of “where will the tax dollars come from?” looms ever larger, especially in light of the ballooning federal debt due to a series of pandemic stimulus packages.