In the previous article, we discussed all the ways the US Government, via the IRS, incentivises charitable contributions. In this article, we’ll discuss how to develop a giving strategy that won’t “break the retirement bank.”

You probably won’t be surprised to learn that this is a little more challenging than it sounds, due to the numerous variables involved, not the least of which are the simple desires to be increasingly generous in retirement, especially as we age, while also providing for ourselves for the rest of our lives.

Christian retirees are (relatively) generous

Christian retirees, as a group, tend to be pretty generous. Some recent surveys (Giving USA and others) suggest that giving to religious concerns (churches and causes) averages about $2,500 annually among that group.

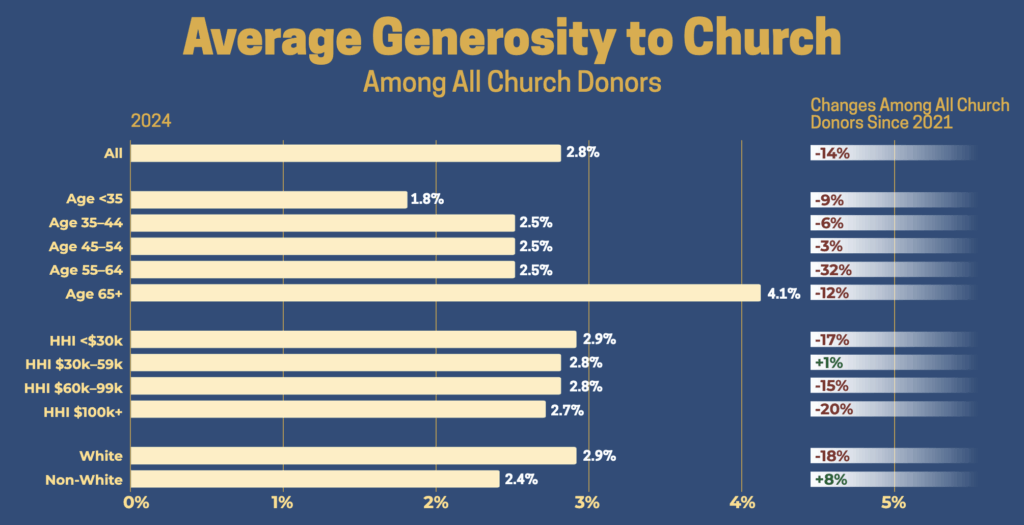

Total charitable giving by those aged 65 and older is higher as a percentage of income than that of younger groups:

Source: ”The Giving Gap: Changes in Evangelical Generosity (2024)”

Most studies indicate that participation rates (the percentage of people who contribute anything) are also exceptionally high among older cohorts. The Giving Gap study also found that,

When we consider only those who give to church, the average evangelical church donor gives away 2.8% of household income to church, with a median of 1.1%. Unfortunately, both of these figures are down from 2021, when the average was 3.2% and the median was 1.3%.

Obviously, the average giving cited in this study is nowhere close to the traditional “tithe” of 10%; it’s not even half or a third. However, annual giving of $2,500 might be extravagant for someone with only a small Social Security check and savings of $200,000. It isn’t for someone with a big Social Security check and a retirement portfolio of $1.5 million.

It’s the “wealthier” retirees that I have in mind as I write this article—those with Social Security and mid to high 6-figure to low 7-figure retirement portfolios.

I believe that many Christian (and even some non-Christian) retirees want their later years to be characterized by a reasonable amount of financial security and greater generosity. They want to give faithfully to their church, ministries, and missions, and they may also want to bless their children and grandchildren while they’re still living.

Do not neglect to do good and to share what you have, for such sacrifices are pleasing to God. (Heb. 13:16, ESV)

The challenge, of course, is knowing how much you can give without a serious risk of running out of money before you (or your spouse) runs out of life.

The approach I will propose to you to help you maximize your “regular charitable distributions” (that’s a play on the “Required Minimum Distributions” term the IRS use for traditional IRA withdrawals; not that clever, I know) is a relatively simple framework that I came up with and have basically been using, which may help take some of the guesswork out and help you realize your goals to be more generous as you grow older.

The retirement giving challenge

Most retirees will have two primary sources of income: Social Security and withdrawals from IRAs or 401(k)s, which, for some, may be more than needed due to Required Minimum Distributions (RMDs). The income from both sources may increase due to inflation adjustments to Social Security, investment growth in your IRA or 401(k), annual increases in your RMD percentage, or a combination of all the above.

Of course, your portfolio value can also decrease due to withdrawals and investment losses. That’s why some of us who want to be more generous in retirement may be reluctant to do so, as, in theory, it will exhaust our savings faster if our investments don’t perform well.

I admit that this is a challenging thing to navigate – mentally, emotionally, and spiritually.

On the one hand, we want to be generous, but on the other, we also need to wisely steward the resources God has given us to provide for ourselves and our families. We know that everything ultimately belongs to God, and we’re not to put our hope and faith in our IRA balances or trust in them for our future security; our faith and trust are in the Lord.

A giving strategy you can live with

I believe that any solution you implement begins with a generous heart, which prompts you to consider responding in the moment to an urgent need that God places before you. It also helps you determine how much you can reasonably afford to give on an ongoing basis.

Later, a generous heart will prompt you to consider when you might be able to increase it, and by how much, and without impacting either 1) your ability to provide for you and your family, or 2) your goals in terms of leaving a financial legacy/inheritance if that’s a priority for you.

To do that, you have to consider these critical factors wisely:

- Your and your spouse’s longevity (one of you may live to 90 or beyond)

- Your portfolio performance (which can be very unpredictable)

- The reality of RMDs (which can force larger withdrawals later in life)

- Your desire to include family giving along with charitable giving

- Your desire to leave a legacy (inheritance)

Many Christians have set a goal of giving at least 10% of their annual income to charity, and some retired individuals have also adopted this approach. (That would certainly be far greater than the averages.) For some, this will be relatively easy; for others, it will be a significant stretch—aspirational at best.

I’ve been giving regularly since I retired, and as I shared in a previous article, I maintained my level of giving at or above what it was before I retired. I have also been increasing it since I recently started making Qualified Charitable Distributions (QCDs), which allows me to save more on taxes than when I was only taking the standard deduction.

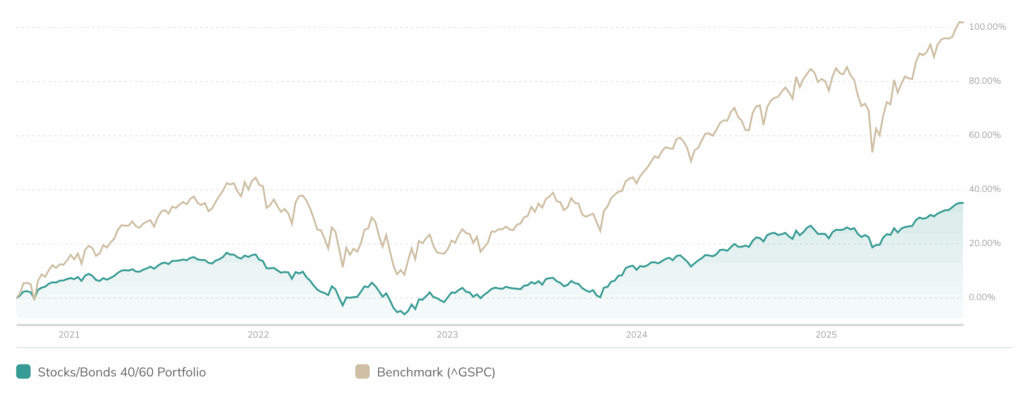

The value of my moderately conservative (≈ 40% stocks/60% bonds & cash) investment portfolio is approximately 11.6% higher today than it was when I retired in 2018, despite all the ups and downs and annual withdrawals I’ve made since then.

However, as we all know, if I were to look back at a different 6-year period, such as 2006 to 2012, it would look very different; the return (without withdrawals) would have been lower—by about 7%—due to lower interest rates and significant losses in the stock market in 2008. If I had retired in 2006 and started making withdrawals, it would have been even less.

The markets have been quite volatile over the last five years or so; 2022 was particularly challenging for those with conservative to moderately conservative portfolios.

Bond losses that year were historic. US Treasury bonds experienced one of their worst years ever. 20-Year US government bonds lost 29%, and 10-Year US government bonds lost over 12%. Even typically low-volatility short-term Treasurys and mortgage-backed securities lost 4% and 12%, respectively.

It was truly a challenging year for bonds, but 2022 was also one of the worst years for stocks, as they declined by over 18%.

The last couple of years, however, have been choppy, but overall, they’ve been positive. As the Ibbotson chart below shows, the overall trend has been up since a low point in October of 2022:

I share that market and portfolio information to say that portfolio performance and survivability is a key consideration in coming up with a giving policy as it affects your ”sustainable withdrawal rate” (SWR), which is generally defined as the percentage of your savings that you can withdraw each year without running out of money, commonly in the 4% range, adjusted annually for inflation. Many people include giving in their SWR.

As you’ll see, I have factored that into my overall strategy. Here are the steps involved:

Step 1—Establish a giving ”floor”

Set a minimum amount that you will give each year, such as between 5% and 10% of your combined Social Security and IRA withdrawals. That becomes your baseline, your “floor.” The simple formula would be:

Giving Floor$ = (IRA/401(k)/Pension/Annuity/Other$ + Social Security$) * Giving%

That’s basically what I did when I retired; however, my percentage was already higher than 10% when I was working, and I maintained the same giving amount after I retired. Consequently, my starting base percentage was even higher, as my retirement income was approximately 15% lower than my income while I was working.

My decision upon retirement was not to get bogged down in determining what percentage of this or that is “tithable,” but instead to maintain my level of giving and increase it over time if possible. (I’m not saying that’s best for everybody; it’s just where I landed on the matter.)

Until you’re eligible to make QCDs (age 70½), you can make charitable contributions from your income, savings accounts, or, if you have any, from appreciated stock. However, once you qualify to make QCDs, you’ll probably want to fund your “floor” with them. QCDs count toward your RMDs and reduce your taxable income at the same time.

Setting a giving floor means that you’d never give less than X% or X$, no matter what the markets do. (Of course, if we have a total market meltdown, that’s a different matter. And you’re free to reduce it if you get really uncomfortable with what’s going on or have a major, unexpected expense. But generally, this is a fixed amount or percentage that you’re trusting the Lord to provide.)

Step 2—Add a surplus percentage

If your investment portfolio is performing well and you have more than enough income to cover your living expenses and give a floor, consider giving a percentage of the surplus.

For example, suppose your Social Security plus income from your IRA sustainable withdrawal rate (SWR), or your RMDs (which may be roughly equal to your SWR), is $130,000. Still, you only need $120,000 (including your 10% giving floor). In that case, you have a $10,000 surplus.

Then, you might decide to allocate X% of that surplus in addition to your 10% floor. In this case, if you gave 60% ($6,000), your total giving would now be $19,000, or 14.6% (=$19,000 ÷ $130,000).

A way to view this formulaically would be:

Surplus$ = (IRA Withdrawal/RMD$ + Social Security$) – (Core Spending$ + Giving Floor$) * Giving%

This approach allows your giving to increase as God blesses you, while still safeguarding your financial stability.

Step 3—Set guardrails

I stated in step #1 above that it would be good not to change our giving floor, regardless of what the markets do. However, for those of us who want to be as generous as possible while also avoiding giving more than is sustainable, you may want to set some guardrails.

For example, you could cap your giving at 1-2% of your average 5-year portfolio value. If your portfolio falls by more than 20% or your financial plan appears underfunded, consider reducing your giving back to the 10% floor until the situation improves.

To illustrate, let’s say you started in 2025. Your current portfolio value is $850,000. However, looking back five years, using your year-end balance for each year, calculates an average portfolio balance (including any deposits, withdrawals, as well as income and capital gains) of $790,000.

If you capped your total annual giving (floor plus surplus) at 1.5% of the 5-year average, that would be $11,850 (= .015 * $790,000).

As you can see, this approach allows you to adjust your giving smoothly in response to market performance. If you had a really bad year and your portfolio lost 20%, your balance might drop to $680,000. That decline would pull your 5-year average down as well—say from $790,000 to about $750,000. In that case, your giving cap would drop to $11,250 (= .015 * $750,000).

Step 4—Consider another (more complex) option—your ”funded ratio”

I stated earlier that a major challenge to generosity for retirees is the concern that they might run out of money. The funded ratio (FR) is a calculation that assesses whether you have sufficient funds to meet your essential needs, possibly with a margin of safety, also taking into account any inheritance or legacy you wish to leave behind.

The problem is that this is a much more complex calculation that is best done with an online calculator. However, the basic formula would be as follows:

Funded Ratio (FR) = Assets ÷ (PV of lifetime spending needs + reserves + legacy bequest)

(PV=Present value, which Investopedia defines as “an estimate of the current value of a future sum of money, is calculated by investors to compare the probable benefits of various investment choices.” In this context, it’s how much money you need today to fund all your future expenditures, taking into account what the money might earn in the future and the impact of inflation.)

You can use a retirement calculator at Fidelity, Vanguard, Schwab to do the calculation, plus Excel and Google Sheets have a built-in formula for this:

=PV(rate, nper, pmt)

But here’s a really easy rule of thumb-type approach: Figure out how much you’ll need each year in retirement, subtract guaranteed income (Social Security, pensions), and multiply the gap by 25. That’s your target amount to have saved now.

I used the spreadsheet formula above to calculate the PV of $30,000/year at a 2% real return (accounts for inflation) for 25 years. The present value (PV) is approximately $603,000. Your current balance is $525,000; therefore, the FR is as follows:

FR = Assets ($525,000) ÷ PV of Lifetime Spending Needs ($603,000) = .87

An FR of 1.20 (equates to 120%) or higher could be considered ”well funded,” meaning you have at least 20% more than you need—a surplus. If your FR is between 1.0 and 1.19, you’re in the ”okay” range—i.e., “fully funded.” There, you may want to stick with your giving floor only.

If your FR slips below 1.0 (indicating you may not have enough to cover your spending and giving plan), or if your portfolio has dropped by more than 20%, you may want to exercise greater caution.

However, remember that the PV calculation assumes fixed spending over a fixed horizon. It prices your retirement like a guaranteed annuity: $30,000 × 25 years at a 2% real return = $750,000 needed. In real life, retirees often adjust their spending when markets fall, shorten their time horizon as they age, and carry cash/bonds to smooth out downturns. This formula ignores all that.

Also, keep in mind that many (most) retirees have other income sources, such as a pension or Social Security (or both), which may cover a large percentage of their spending needs. Once we net that out, the ”gap” your portfolio has to cover is much smaller.

Still, using this kind of approach keeps your giving responsive to real financial conditions without being overly reactive to short-term market noise. It builds in both generosity and prudence: when you’re well-resourced, you give more; when times are lean, you protect your ability to provide for yourself and your family, while also maintaining your faithful giving over the long haul.

Step 5—Give more aggressively later in life

Many couples want to give more as they age. One reason is that they begin to realize that they’re probably not going to run out of money, but there are others.

Giving becomes easier because RMDs increase annually after age 73, thereby improving your income, unless your IRA balance is significantly lower, which can occur due to market downturns or additional withdrawals. If you don’t need the extra RMD income, you could add some or all of it to your floor + surplus giving.

Additionally, in their late 70s to mid-80s, retirees’ living expenses tend to decline (with less travel and smaller homes, for example), freeing up more income for giving.

A wise approach to increase giving during this time would be to plan for a giving “step-up” at a specific age, such as 75, 80, or 85 years old. At that point, you might raise your giving floor from 10% to 12–15% of income, or increase your surplus amount (and perhaps your cap), or both, knowing that you may not need as much for yourself.

A simple example

Let’s say you’re 73 years old and relatively affluent:

- Portfolio: $1.2 million (5-year average = $1.03 million)

- Social Security: $50,000

- IRA SWR (or RMD): $48,000

- Total income: $98,000

- Core Spending: $80,000

- Income needed from portfolio: $30,000

Here’s how the framework and formula might look:

Giving floor:

Giving Floor$ = 10% * $98,000 (Total Income) = $9,800 (funded with QCDs)

Surplus giving:

Surplus$ = (IRA Withdrawal/RMD$ + Social Security$) – (Core Spending$ + Giving Floor$) x Giving%

Surplus$ = ($48,000 + $50,000) – ($80,000 + $9,800) = ($98,000 – $89,800) = $8,200 * 60% = $4,920.

Total giving:

Total Giving is $14,720 (= $9,800 + $4,920), which is approximately 15% of income and within the 1.5% Cap ($15,450) of the 5-year portfolio average ($1.03M).

With a 20% loss in the next year:

The portfolio balance is now $960,000 (= 0.80 * $ 1.2 million).

The 5-year average will also decline, but not as sharply, as it smooths out over multiple years. For illustration, let’s assume it drops from $1.03M to about $975,000 (roughly a 5% decline in the average). Consequently, the new giving cap is $14,625 (= .015 * $975,000).

Total giving is now ($9,800 + $4,920) = $14,720. But this year, the cap is $14,625, which is slightly lower. You may want to reduce your sustainable giving amount to $14,625 from $14,720.

That’s not a significant change, but you have flexibility in how you calculate your cap and the amount to which it will be applied. Some, for example, may use a year-by-year calculation (instead of a multi-year average) to set their cap.

PV/FR Analysis:

The core spending need from the portfolio is $30,000/year (= $80,000 – $50,000). The PV of that amount over 25 years at a 2% real return is approximately $573,000. Therefore, FV = 960,000 ÷ 573,000 ≈ 1.67. That FR is comfortably above 1.2, which means that ”floor + surplus” giving is feasible, and there may be room for additional surplus giving.

Taxes:

If you’re wondering about taxes, in this example $30,650 of your Social Security benefits is taxable. With an AGI of $78,650, your taxable income is calculated as follows: AGI ($78,650) – Standard Deduction ($34,700) – Senior Deduction ($12,000) – QCDs ($14,720) = $17,230.

The 2025 federal income tax is approximately $1,723 (= .10 * $17,230). That’s an effective tax rate of only 2.2%!

Don’t forget family giving

Generosity isn’t just about your church and other ministries; it can also be about blessing your family. As you grow older, if you’re able, you might consider:

- Annual tax-free (for them) gifts to children or grandchildren (the annual exclusion is $19,000 per recipient in 2025).

- Funding 529 college savings plans or the new ”Trump Account” for grandkids.

- Family experiences, like paying for a vacation that brings everyone together.

By planning family giving as part of your overall generosity framework, you can be intentional without neglecting your other charitable commitments.

I try to “practice what I preach”

You may wonder whether my wife’s and my giving aligns with the guidelines I outlined in this article.

Well, in the interest of transparency—and certainly not to boast, as I’m sure there are many of you out there who are more generous than I am—and so that you know that I try, by God’s grace, to “practice what I preach,” our annual “core giving” plus “surplus giving” is currently approximately 23.5% of our gross income, which consists of Social Security and RMDs from my IRA.

Additionally, it accounts for approximately 1.32% of our portfolio’s average 5-year balance (January 2020 to December 2024).

We use QCDs for most of our major giving, but we also make some cash gifts directly ($2,000 of which is now deductible under the OBBBA!).

My current FR is fairly good at 1.45, as it exceeds 1.2. As I increase my giving in the years ahead, I’ll closely monitor that ratio to help me decide what I’m comfortable with. I’m in pretty good shape right now, but as we all know, things can change fast. Additionally, my wife and I are discussing taking at least one or two overseas trips (perhaps a cruise) before we’re too old, and that would significantly reduce our savings.

By establishing a floor, adding a surplus share, setting guardrails, and planning to increase giving later in life, we can cultivate generosity without fear of depleting our financial resources. I hope the guidance I offer in this article helps you to do the same.

Each one must give as he has decided in his heart, not reluctantly or under compulsion, for God loves a cheerful giver. (2 Cor. 9:7, ESV)