I’ve recently had the opportunity to discuss the rationales and mechanics of IRA transfers, 401(k) rollovers, and ”Solo” 401(k)s with a few folks.

It’s not uncommon to want to focus on getting on our ”financial ducks in a row” at the start of a new year. For some, that means simplifying their financial life and accounts, including retirement savings accounts.

Many people have multiple retirement accounts and may want to (and probably should) consolidate when it makes sense. To do that, you have to do either a transfer or a rollover (and sometimes both).

The IRS rules permit tax-free rollovers and transfers that enable you to move your retirement savings from one financial institution to another and from one type of account to another, and it’s possible to consolidate multiple accounts into a single account.

The reasons, rules, and processes for transfers and rollovers are different and also vary based on the type of account.

This is the first of two articles on retirement account consolidation using rollovers and transfers to help you simplify your retirement finances while avoiding costly mistakes (taxes and penalties).

In this post, I discuss the difference between a transfer and a rollover and dive deeper into transfers. In the next one, we’ll look at rollovers.

Account transfers versus rollovers

The terms transfer and rollover are sometimes used interchangeably, with rollover being the most common. But for these two articles, I’m going to make the following distinctions:

A transfer is when you move assets between two of the same types of retirement account, e.g., from a Traditional IRA to a Traditional IRA.

A rollover is when you move assets between two different retirement accounts, e.g., from a Traditional 401(k) to a Traditional IRA.

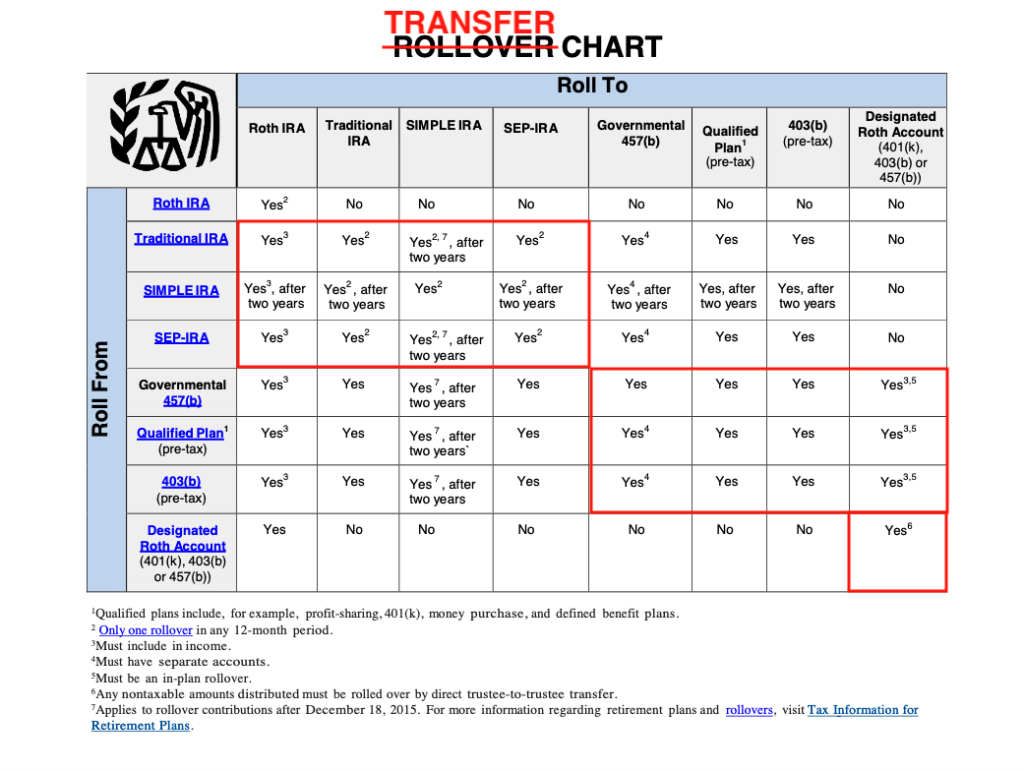

Both are allowed by the IRS, providing certain conditions are met. I’ve modified the following “Rollover Chart” from the IRS (they don’t distinguish between a transfer and a rollover in the same way I do) to show the various transfer possibilities (highlighted in red).

I’m making the transfer delineation based simply on like-to-like transfers (e.g., Roth IRA to Roth IRA). I’ll identify the others as “rollovers” (e.g., Traditional 401(k) to Traditional IRA), which I’ll address in the next article.

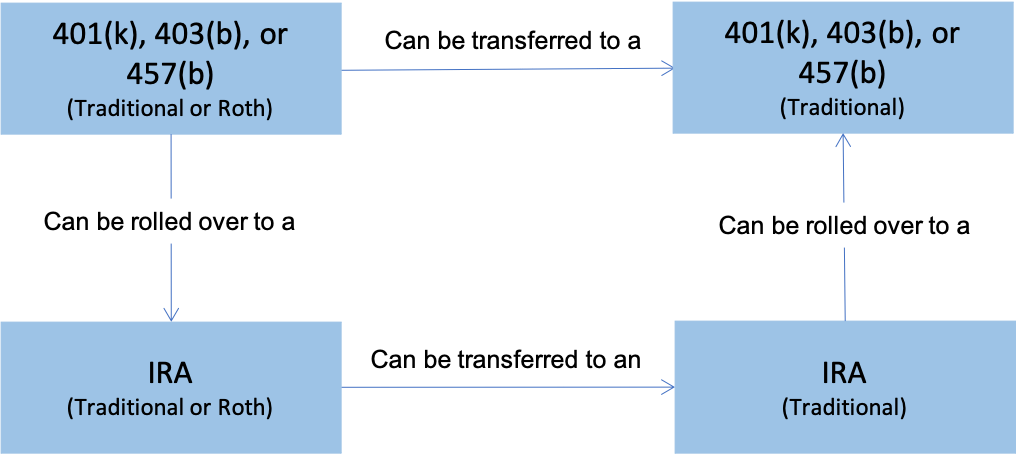

As you can see, because of the multiple account types, there are many transfer and rollover options. And in some scenarios—such as Traditional IRA to Roth IRA—there are tax consequences (as you have to do a Roth Conversion). So, for purposes of this article, here’s a simpler diagram to help you better visualize the possibilities:

These are non-taxable events if done correctly. (An exception would be transferring a Roth IRA to a Traditional IRA—a Roth Conversion.) But mishandling any of them could result in a taxable event and may even incur other financial penalties.

So, it’s crucial to understand the different types of transfers and rollovers and the IRS rules for each of them. (In other words, not just what you can do and why you would do it, but also how to do it to keep the IRS happy.)

As you can see from the IRS chart and my diagram above, you’re allowed to do a tax-free transfer from:

- a Traditional 401(k) with a former employer to a Traditional 401(k) with a new employer

- a Roth 401(k) with a former employer to a Roth 401(k) with a new employer

- one Traditional IRA to another Traditional IRA (one financial institution to another)

- one Roth IRA to another Roth IRA (one financial institution to another)

401(k) transfers

Some people may want to transfer an old 401(k) with a former employer to a new employer’s 401(k). I’ve never done this as, when I left an employer, I rolled my 401(k) balance into my IRA. (All of my retirement savings are now in a Traditional IRA and a smaller Roth IRA.)

This scenario typically occurs when you leave a job, no longer contribute to your former employer’s retirement plan, and work at a new employer and participate in their plan.

It could also occur if you leave an employer, become self-employed, and contribute to a Solo 401(k). The IRS defines a Solo 401(k) as “. . . a traditional 401(k) plan covering a business owner with no employees, or that person and their spouse. These plans have the same rules and requirements as any other 401(k) plan.”

Generally speaking, most people will be better off doing a rollover to an IRA (more on that in the next article). However, according to Investopedia, there are some good reasons to keep your savings in your employer’s 401(k):

- Leaving your 401(k) account with your employer can save you fees since the company can buy funds at institutional pricing rates.

- If you own appreciated company stock in your 401(k), transferring the stock to a brokerage account instead of an IRA can save on taxes.

- Not rolling over your 401(k) can help with legal protection in bankruptcy and provide access to your money at an earlier age.

- Company 401(k) plans have access to stable value funds, similar to money market funds, but offer better interest rates.

- If you want to retire early and leave your job at age 55 but before at 59½, you can withdraw funds from your 401(k) without incurring the additional 10% tax penalty that usually applies to retirement account withdrawals before age 59½.

Another advantage of transferring from one 401(k) plan to another, especially for older employees, is that your savings are subject to required minimum distributions (RMDs). (They would be if kept in the old employer’s plan or rolled into an IRA.)

Whether you decide to transfer your 401(k) or not, be sure to make the most of it.

How to transfer to a new 401(k)

(Note: This information would also apply to 403(b) and 457(b) employer plans.)

The main thing to know about 401(k) transfers is that not all employer-sponsored plans allow them. So, the first thing to do is to ask your new plan sponsor, custodian, or HR person who specializes in assisting employees with their 401(k) plan.

If transfers are allowed, your employer will have a prescribed process you must follow, which will probably involve a lot of paperwork. Once the paperwork is complete and processed, the transfer can begin. But this is where things can get tricky.

When you make the transfer, you’ll have to give both the old and new 401(k) plan administrators detailed information on what you want them to do with the assets you’re transferring. How you accomplish that will depend on whether you do a direct or indirect transfer.

A direct transfer is just what it sounds like—from one plan custodian to another, typically done electronically (no paper checks involved).

In most cases, with a direct transfer, you’ll have to liquidate your investments to convert them to cash so that you can transfer the funds. In rare instances, you can do an “in-kind” transfer whereby your existing investments are transferred.

A slightly more risky option is the indirect transfer (what the IRS calls a “60-day rollover”). In this case, you request the account proceeds in the form of a check to be sent directly to you. If you do, the custodian must assume that you are liquidating your account and are therefore obligated to withhold income taxes (20% federal tax plus a 10% penalty if you’re under age 59½), even if you intend to deposit it back into another 401(k) or IRA.

Why would anyone want to do this? The best reason I can think of is that the new employer’s 401(k) plan does not accept direct transfers, and an indirect transfer is the only way to get it done.

Another reason could be that someone needs the temporary use of the money for a portion of the 60 days, but then they have to come up with the total amount and deposit it in time to avoid the withheld taxes becoming permanent.

If done correctly, neither a direct transfer nor a 60-day rollover from one 401(k) to another will create a permanently taxable event, nor will they incur an IRS early withdrawal penalty. (We’ll discuss this more in-depth in the “What if you mess it up?” section below.)

IRA transfers

An IRA transfer is when you move your IRA from one financial institution to another (e.g., from Fidelity to Vanguard or vice-versa). I have only done this once—when I transferred an IRA from Vanguard to Fidelity, which I did to consolidate and to take advantage of Fidelity’s online brokerage platform and because I wanted to diversify out of mainly Vanguard funds (although I still own some in my Fidelity account).

Now, if I wanted to transfer my Fidelity Roth IRA brokerage account to a Schwab brokerage account, for example, I could do that as a Roth IRA transfer.

The process for an IRA transfer is very similar to transferring a 401(k).

There are many reasons that you might want to do this, but I have found that the most common is to move an IRA from a high-fee, advisor-managed account to a self-directed, lower-cost alternative.

Some fee-based advisors charge as much as 1% or more and may also use higher-cost actively managed mutual funds in their clients’ accounts, driving costs even higher.

If you want to move from a high-cost broker to a low-cost provider, such as Fidelity, Schwab, or Vanguard, you must do an IRA transfer.

When you transfer, funds or assets (specific securities positions) are sent directly between the institutions—you never see the money at all. As with a 401(k) transfer, this is usually the fastest and most reliable method of moving an IRA.

An alternative is to do an indirect transfer (the 60-day rollover method). Still, as with employer accounts, you’ll be subject to federal tax withholding and an early withdrawal penalty, depending on your age.

Importantly, when you transfer an IRA, you have to move from one type of IRA at one institution to the same type of IRA at a different one. In other words, you have to transfer a Traditional IRA to a Traditional IRA and a Roth to a Roth. You can’t move a Traditional IRA into a Roth IRA unless you do a Roth Conversion.

As you may have seen in the IRS chart above, you can also transfer to SIMPLE and SEP IRAs under certain conditions. SEP IRAs are like Traditional IRAs when transferring—you can move these accounts to other SEPs and Traditional IRAs.

SIMPLE IRAs can also be moved to a Traditional IRA, but only if you’ve had the SIMPLE IRA open for at least two years. You can move these funds back to a SIMPLE IRA as well, but only after they’ve been in the Traditional IRA for at least two years. It would be best to clarify before opening your account that the plan type is right for your goals and the contributions you hope to make.

(They’re hard to read, but the footnotes in the IRS chart are very important.)

How to transfer an IRA

Transfers are typically initiated at the company where you want to move the IRA. For example, if you wish to move your IRA from Schwab to Fidelity, you would first go to Fidelity and start the process online. (Most large institutions will have an online process while others will use a transfer form with instructions.)

Whether the process is online or using paper forms, the steps would be very similar:

- Compile all the needed information.

- Complete the necessary forms and send them to the existing custodian.

- Start the transfer and verify when complete.

- Decide how to invest the transferred assets (if not transferred “in-kind”).

As with a 401(k) transfer discussed previously, you can do an all-cash transfer, but you will first need to liquidate any assets and convert them to cash. Another option is to do an in-kind transfer.

When transferring assets in-kind from your previous IRA custodian, they will have to be reregistered in the name of the new IRA. Some custodians require certain guarantees before receiving in-kind transferred assets.

What if you mess it up?

All in all, the transfer of either a 401(k) or IRA from one plan or custodian to another is relatively straightforward. However, it is not ”risk free,” meaning if you don’t follow the IRS rules to the letter, you could find yourself with a hefty tax bill and other penalties.

The first challenge comes when you do an indirect transfer and receive only 70% to 80% of your current account balance due to tax withholding and possibly an early withdrawal penalty. (That money is sent by your employer or account custodian to the IRS.)

You then have 60 days to deposit 100% of your original balance into the new account. To do so, you’ll have to come up with the 20% or 30% that the IRS deducted.

If you deposit it into another account within the 60-day window, you will need to report the distribution on your tax return. Still, you will also show that you deposited the entire amount back into another retirement account within the allowed period.

That would result in an IRS refund of the taxes (and any penalty) withheld, which you can then redeposit into the new account if you could not come up with the 20% to 30% extra to make the full transfer.

But what if you miss the 60-day rollover window. (It doesn’t start from the date you requested the rollover, it begins when you receive the money, typically in the form of a check or direct deposit to your bank account.)

If you miss the deadline because you haven’t cashed the check (i.e., did not have ”constructive use” of the money), you may still be able to get the entire amount back into an IRA and undo everything.

If you miss the 60-day window completely? Fortunately, the IRS has provisions in their rules for automatic and on-request waivers: “The IRS may waive the 60-day rollover requirement in certain situations if you missed the deadline because of circumstances beyond your control.” That’s good news for anyone who misses the deadline, but waivers aren’t automatic.

If you don’t receive a waiver, you can’t put all the money directly back into a retirement account in the year you made the withdrawal. Your next option is to minimize the tax impact and rebuild your retirement savings account by using the money to increase your contributions in the following years.

If you and your wife are both working, you could max out both of your 401(k)s and IRAs each year—a substantial annual contribution.

These potential risks are why I (and most financial professionals) don’t recommend indirect rollovers. Even if you do it perfectly, you still have to come up with the 20% to 30% of your original account balance to fund the new account fully. Plus, you won’t get it back until you file your taxes returns in the following year.