(Note: We all have our eyes, hearts, and prayers directed toward what is going on in Ukraine. But with everything happening in the world—globally and domestically—I think part of good retirement stewardship is acquiring understanding so that we can make wise decisions about how to manage God’s money during difficult times (Prov. 1:5). If you need some encouragement, scroll down and read the last section first. Also, apologies in advance for the longer-than-normal article—and “nerdier” than usual with several charts—but there’s a lot to explain and discuss.)

The bubble has burst! (Or should I say bubbles?)

Yes, many said it would happen, and we thought it would happen, eventually, even if we didn’t know precisely why or when.

After so many good years, it seems almost surreal that it has.

And it’s not just the stock market bubble; it’s the bond market too. And it’s affecting almost all of us. Will the housing market be next?

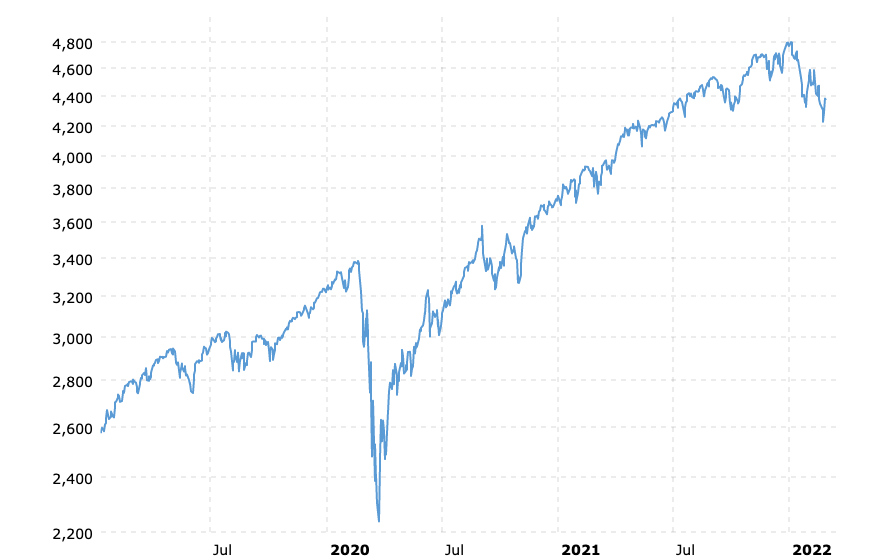

As you can see from the following chart, the S&P 500 was already near correction territory before the Russian invasion of Ukraine, which is defined as a 10% to 20% drop from its latest peak. The index ended Feb. down 8.81% YTD.

S&P 500 Market Index Daily Chart (YTD)

Let’s see how the market did leading up to and then during another world crisis, the 2020 to 2022 pandemic:

S&P 500 Market Index Daily Chart (2020 to Present)

The above chart dramatically depicts the 34% pandemic correction in February and March of 2020 and the fact that it finished the year up 18%. I’m not saying that’s likely to happen in 2022, but rather that it can happen.

The market was calmer in 2021, with the S&P500 finishing up big, almost 29% as the economy was flush with fiscal stimulus and continued to recover.

If you look closely at the above chart, you’ll notice that although the index is down a lot since its most recent highs, it’s still quite a bit higher than it was for most of 2020 and much of 2021. So, it doesn’t look quite so bad when you take a wider perspective.

Retirees (like yours truly) who rely on their investments to fund part of their retirement have seen their account balances fall precipitously since the end of 2021, regardless of whether they’re invested mainly in stocks or bonds.

Near-term retirees (those planning to retire in the next 3 to 5 years) and recent retirees face a “sequence of returns risk” if their assets continue to depreciate.

It’s all very concerning. But, as faithful stewards who know that God owns it all, we can seek to wisely pursue knowledge and understanding to faithfully manage the resources he has entrusted to us (Prov. 27:1).

We all need a general understanding of the economic climate we’re investing in, whether we’re do-it-yourselfers or paying someone to manage our investments for us.

So, in this article, I’ll try to summarize how the war in Ukraine, the fed, interest rates, inflation, and the stock market are impacting us.

Once we understand what’s happening and why we can consider what it means to be a good steward and ask ourselves this question: “What should we do, if anything, to better position ourselves and our portfolios for these negative impacts”?

Major forces at play

Major economic forces are at play due to 3 primary causes: #1 – geopolitical instability (war in Ukraine), #2 – raising interest rates, and #3 – “quantitative tightening (QT).”

All of these are impacting the financial markets, and therefore our portfolios, in similar—and mostly negative—ways.

#1 – War in Ukranine

War creates uncertainty, which is something the financial markets hate. And they’ve reacted accordingly.

In this specific case, both Ukraine and Russia are commodity producers, notably oil and gas and agricultural products. The war and sanctions imposed by allied governments to punish Russia for its aggression will create shortages in Europe and the U.S., leading to higher inflation.

Oil prices, which were already up as the pandemic abated, are continuing to rise:

Crude Oil Prices (Per Barrel)

This is especially impactful since we were already experiencing high inflation, which many attribute to pandemic-caused supply problems and high levels of federal stimulus. Moreover, the prospect of rising energy prices amid an aggressive fed policy pivot focused on reducing inflation has significantly impacted investor sentiment.

#2 – Rising interest rates

One way (and some would argue the most impactful) the fed implements its monetary policy is by manipulating interest rates.

They typically do this by changing the fed funds rate, the interest rate commercial banks and credit unions lend their cash reserves to other institutions overnight. (Some would argue that the fed funds rate is the most powerful economic force in the world today.)

The fed funds rate is different from the discount rate and the prime rate, but they’re closely related.

The discount rate is the fed’s rate to lend to member banks when they have temporary problems obtaining funds to meet their reserve requirements or other short-term funding needs.

The prime rate, which is currently the fed funds target rate + 3%, is used by most banks as a baseline for what they charge on many consumer loan products, such as car loans, credit cards, and home equity lines of credit (HELOC).

Thus, any loan tied to the prime rate will change when the fed fund rate changes.

The fed lowers short-term interest rates (by reducing the fed funds rate) to ease the U.S. financial system’s stress and spur economic growth. It raises the fed fund rate to accomplish the opposite: slow an overheated economy to reduce inflation.

A commonly cited metric is the fed target inflation rate, combined with employment numbers. The fed tries to hit those targets as a policy goal.

Beginning in 2021, as inflation continued to rise to levels not seen in several decades, the fed signaled its intent to raise the fed funds rate starting as early as March 2022.

Despite the war in Ukraine, many still expect the fed to raise the fed funds rate—perhaps less aggressively—by 25 or maybe 50 basis points this month. And additional staggered increases may follow.

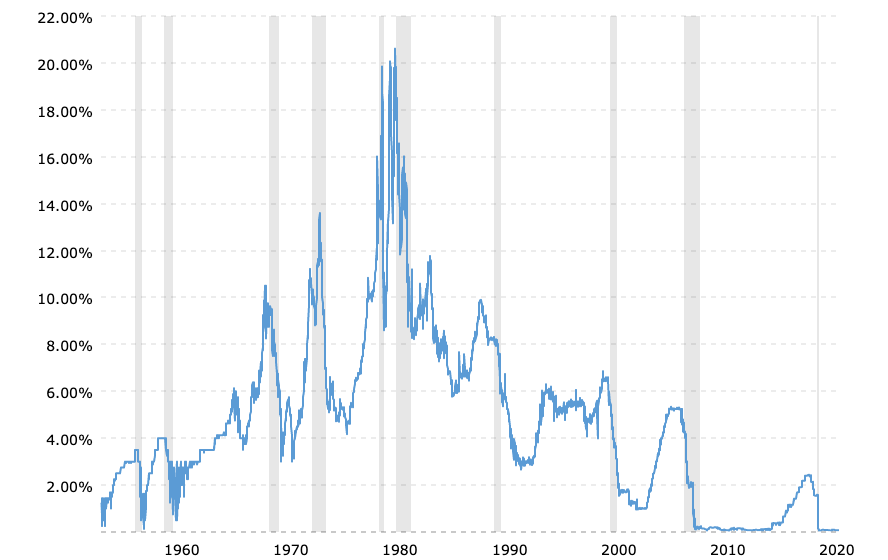

This chart shows the fed’s rate change actions during multiple recessions (the gray shaded areas) and then again on the heels of the 2020 pandemic. (Although it has recently been near 0%, it was once as high as 20%. I remember having a 12% adjustable-rate home mortgage during that time!)

Fed Funds Rate Historical Chart

Compare that chart with this one showing the decline of the benchmark 5-year US Treasury Bond:

5-Year Treasury Bond Rate Yield Chart

The causative relationship between the fed fund rate and other short- to medium-term interest rates is obvious.

The net effect of these, along with other actions in recessionary times (or times of crisis), was a “propping up” of the stock markets, higher prices for safer assets, and low bond yields across the board.

Over the last decade, near-zero rates helped fuel the bull market in stocks and bonds and the pitifully low yields investors have received from CDs, treasuries, and corporate bonds. Rising rates are likely to have the opposite effect, which is already being felt.

#3 – Quantitative tightening

In addition to lowering the fed funds rate, the fed also uses quantitative easing (QE), or tightening (QT), to manage monetary policy. (With apologies to Albert Einstein, there is no physics involved.)

Whereas lowering the fed funds rate reduces short-term rates, QE mainly reduces long-term interest rates.

The fed implemented QE during the 2008–2009 financial crisis and again during the coronavirus pandemic in 2020.

They made large-scale purchases of mostly longer-term Treasury securities and mortgage-backed securities to do so. (Recently, the fed has even purchased stocks.)

The effects of these purchases were potent. They increased the money supply, which lowered longer-term rates, thereby reducing the cost of long-term borrowing (such as corporate bonds), spurring economic growth.

The goal is to stimulate economic activity during a crisis and keep credit flowing. As mentioned previously, this is done while keeping an eye on two key economic metrics: inflation and employment.

That brings us to where we are now: high inflation and low unemployment, along with low interest rates and high stock valuations. These are signs of an overheated (too well-stimulated) economy, where demand for goods and services (and employees) exceeds demand.

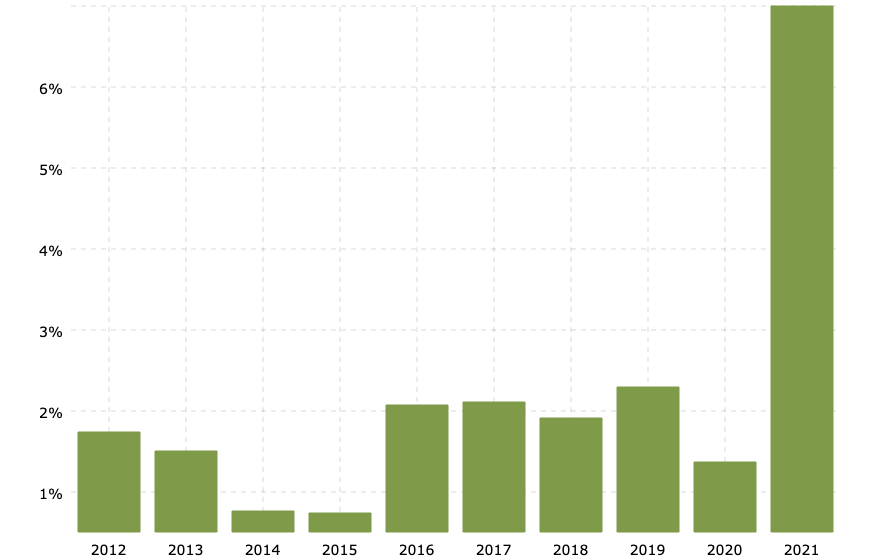

Historical Inflation Rate by Year

Inflation was 7% in 2021, and YTD is now at 7.5% and likely to go higher due to increasing oil and gas prices.

To combat high inflation and increase long-term rates, the fed announced and is already in the early stages of “quantitative tightening” (QT), the opposite of QE.

Although many argue it’s bad for long-term economic health, QE was (generally) good for the economy and investors in stocks and bonds. Thus it’s reasonable to expect that QT may do the opposite, albeit while lowering the inflation rate, an arguably noble goal.

To implement QT, the fed will wind down their purchases of assets and may eventually sell them. And they will do this in conjunction with raising the fed funds rate.

These actions should reduce demand for assets like government and high-quality corporate bonds. As bonds are sold off, prices fall, but yields will rise.

There’s a rule of thumb that some forget about when buying bonds: interest-rate sensitivity and risk. For each 1% increase in interest rates, a bond (or bond fund) will decrease in value by a percentage equal to its effective duration.

What this means for you and me

What all this means to an individual investor has everything to do with their individual portfolios’ asset types and allocations.

From there, it depends on what stage of life they’re in, their risk tolerance, and their specific retirement goals. So, there’s no one way to describe how this will impact us.

I can, however, describe what’s going on in my own portfolio (which may be somewhat typical of others’) and what I am doing (or not doing) at this time.

My portfolio is down YTD

I’ve mentioned before that my investing strategy is “strategic growth and income.” My current stock/bond allocation is approximately 40% / 60%, including 7.5% cash.

Because my portfolio is income-oriented, some of my investments are a tad riskier. As of 2/28, it was down 3.68% overall year-to-date, but still up about 7% since the start of 2021.

But the good news (if there is any) is that even though share prices have fallen, I still receive income from my portfolio, which I use to continually refill my cash bucket.

My stock funds are down

My stock investments are primarily in three high quality, dividend-paying domestic stock funds, two international stock dividend funds, and smaller positions in two small-cap value funds, a preferred stock fund, and two real estate funds. Together, these comprise about 40% of my portfolio.

My stock funds would collectively be categorized as ‘moderately conservative,’ but they are down a weighted average of 5.83 % YTD collectively. However, that’s better than the S&P 500, which is down 8.81% YTD.

The good news is that they’re paying average dividends in the 2 to 3 percent range, which I hope to continue even as their share prices decline. Only time will tell.

My bond funds are also down, but less than stocks

In times of extreme volatility in the stock market, we hope that our bond investments help offset stock losses. Unfortunately, that’s not been the case. My bond funds are down less than my stocks, but they add to my total losses.

Fortunately, they continue to pay interest, which is one of the main reasons I have them in the first place.

I have a sizable investment in an intermediate-term (5 to 10 year) bond ETF with an average effective duration of 5.90 years. (It pays about 2% in interest.)

You may have something similar in your portfolio.

That means that a 1% increase in interest rates (which is very likely to happen over the next 12 mos.) would result in a 5.9% decrease in the fund’s net asset value.

If rates increase less, say 0.50%, the NAV decrease would be 2.95%.

My fund’s performance is already down 3.58% year-to-date (as compared to the category average of 3.23% and its benchmark index of 3.53).

My other bond funds, a TIPs fund and an interest-rate-hedged US bond fund are down 1.44% and 3.07%, respectively.

This is to be expected based on the market’s reaction to the fed announcements on QT and its intent to raise the fed funds rate by as much as .75% to 1.00% over the next 12 months, possibly starting as soon as this month.

Why bonds go down when rates rise

Like me, many retirees have a high allocation to bonds in their retirement portfolios.

Remember, the financial markets move based on future expectations, not what’s going on right now. That’s why yields have risen, and bond fund valuations are down as traders anticipate where rates are headed over the next one to two years.

In other words, the market has to an extent, already baked in these actions, even though the fed hasn’t fully implemented them yet.

More specifically, when traders anticipate that companies and the US government will issue new bonds in the future with higher coupon rates, they decide they can get higher yields elsewhere.

Consequently, they sell their current bonds to purchase newer ones with higher interest rates. If this buying and selling are heavy, it will cause current bond prices to fall.

For example, instead of holding a 7-year bond earning 2%, they may sell that bond and buy one earning 3.0% or 3.5%, or even 4.0%.

Rising rates may also reduce the demand for assets like high-quality corporate bonds in favor of less risky CDs, money market funds, etc. (Due to historically low rates, these have been out of favor for the last few years.)

Still, there is a point where bond yields rise to the point that investors want to buy new bonds, and then the money comes out of CDs and other ‘safer’ interest-paying investments.

Normalization in abnormal times

At this point, it’s hard to tell where all this is headed, and I’m certainly not going to make any predictions.

When interest rates are near zero and inflation is low (like in the last ten years), earning expectations are high, and investors will bid up stock prices accordingly.

But the current environment of near-zero rates and a ‘bubbly’ (not as in cheerful and outgoing, but as in easily burst) stock market is not typical. It points to what the fed has come to realize as ‘too much of a good thing.’

This is especially true since they are combined with the surge of cash due to pandemic-related fiscal stimulus and with the post-pandemic (if I may use the ‘post’ word) phenomenon of surging demand and supply shortages.

The result is exceptionally high inflation; 7.5% (by one measure) over the last year!

So, the fed wants to try to return conditions to normal, which they define as inflation in the 2% range and with whatever level of employment that can support. (They may also want to “reload their monetary and fiscal policy guns” to have something to use to deal with the next economic crisis.)

Normalization seems a worthy goal.

But full normalization may be challenging to achieve anytime soon when considering the amount of fiscal stimulus pumped into the economy and how long interest rates have been near zero. That’s not to mention the new economic factors introduced by the conflict in Ukraine.

What to do?

Ben Carlson, a popular financial advisor and blogger, recently wrote that you have three options during times like this: 1) do more, 2) do less, or 3) do nothing.

If you have an aggressive risk profile, you hopefully have at least 10 or 20 years or more to retirement, so plenty of time to ride out the storm, even if your total returns during that period don’t measure up to those of the last two decades.

Those with more conservative allocations, such as a traditional balanced portfolio of 60% stocks and 40% bonds, have also been hit hard. The Vanguard Balanced Index Fund (VBINX) is down 6.41% year-to-date.

Despite how counterintuitive that may seem, most people may be better off doing nothing. But as stewards who want to honor and obey God, we can prayerfully consider our options and then make wise, informed decisions and move forward in faith and with peace.

I have written about this, but I can’t tell you what to do because I don’t know your specific situation.

I can, however, tell you what I’m doing (or, more appropriately, not doing) or might do in the future as conditions warrant. But first, a little background.

I slowly de-risked my portfolio as I approached and then entered retirement. I went from 60% stocks/40% bonds and cash to a 35%/65% allocation, and more recently, to 40%/60%—ratcheting up the risk just slightly—to generate more income.

Additionally, I set up my “bucket strategy,” which I have faithfully followed.

As part of that strategy, my stock fund holdings are money I don’t anticipate needing for 10 to 15 years, so day-to-day volatility doesn’t bother me much. (Though I’d be dishonest if I said the recent correction doesn’t make me a little uncomfortable.)

So, at least for now, I’m doing nothing. That may be the right thing for you too, but maybe not.

If you are in the “do more” (or at least the “do something”) category, here are some of the things you may want to consider, now or in the future:

Buy assets that are “on sale”

Some people go bargain hunting when the market is down big. I have done it myself over the years.

I think the younger you are (with more time for your “discounted” investments to grow), the more this strategy makes sense.

The challenge is that almost everything is on sale right now, and some may be cheaper in the future. So it’s best to buy a little at a time and leave the door open for future opportunities.

Because I’m already retired, and I know growth stocks are riskier, I’m not interested in investing in them. I’d rather stick with value and quality, focusing on dividend-paying stocks.

Rebalance in the future

I plan to hold on to the bond portion of my portfolio, as well as my stock funds.

It’s my opion that long-term investors should hold on to the bond portion (which is typically 10% to 30% of the total) of their portfolios just as they would stocks, rebalancing to their chosen asset allocation as necessary.

Sure, it can be painful to watch the losses pile up when interest rates rise quickly (just as when stocks fall quickly). However, for a bond fund, as interest rates rise and bonds mature, the fund will begin to purchase new bonds at higher interest rates so that, over the long term, the losses caused by rising rates will be offset by increased interest payments.

You could sell fixed-income assets that haven’t depreciated as much as equities and buy more stocks or stock funds. But that could make your portfolio riskier, significantly so if stocks underperform expectations.

Go to all bonds

More conservative investors (like near-retirees or the retired) may see better bond returns, thanks to higher yields after price declines and rate increases. Some people (like me) may move from dividend-paying funds back to fixed income if yields are comparable.

One this is for sure: the decades-long banquet for investors in bond funds, at least in terms of rising bond asset prices, is over. As rates continue to rise and QT takes effect, there will surely be more volatility, resulting in lower stock prices and bond prices.

But it’s probably best to think long and hard before you dump all your stocks for bonds or vice-versa, or go to all-cash so you can wait it out and then jump back in when the time is right. (One of the greatest challenges is deciding “when the time is right.”)

Buy commodities and /or precious metals

Commodity and precious metal investments (especially gold and silver) are often suggested as possible ways for investors to hedge against risk—especially inflation and geopolitical risks—in their portfolios.

These alternatives have no earnings. But real assets often retain their value and may increase in value when the dollar’s value falls.

In the current environment of high inflation and increasing oil prices, gold and commodities are getting more attention, as are energy stocks.

Though not a real asset, cryptocurrencies also come into the discussion in this context.

Therefore, I will discuss gold as an inflation and market risk hedge in my next article, and I plan to follow it up with an article on crypto.

Sell everything and move to cash

Some may consider selling out and running to ‘cash.’ But if you cash out, you have to decide when to put your cash back to work—that’s the hard part.

Raising more cash may be a reasonable strategy, especially if you can do so by selling assets that have appreciated more than others over the last few years.

And if you’re going to cash out, perhaps you’ll want to consider buying some gold since cash earns nothing and gets eaten up by inflation?

But as rates rise, cash-based assets, such as CDs and money market funds, may begin to look more attractive. If long-term rates go up too, even single premium immediate annuities will look better.

Remember, while QE tended to push investors toward riskier assets, QT may tend to do the opposite.

God over everything

Our God is the sovereign ruler over everything. In these difficult and challenging times, we can be encouraged by Isa. 41:10 (ESV):

Fear not, for I am with you; be not dismayed, for I am your God; I will strengthen you, I will help you, I will uphold you with my righteous right hand.