Over the past few months (and years, actually), I’ve written several articles about taxes in retirement. You can read all of the Retirement Stewardship articles → HERE. If you’re younger, you might want to start with the Tax series on NextGenSteward → HERE.

Honestly, when I retired, I was just as concerned about this as other retirees, as I have most of my savings in a “traditional”—i.e., taxable upon withdrawal—IRA, and I recently started taking taxable Required Minimum Distributions (RMDs).

Plus, it seemed everywhere I looked, someone was sounding the alarm about taxes in retirement and extolling the virtues of Roth accounts, Roth conversions, Backdoor Mega Roth contributions and conversions, and even some forms of life insurance as a way to deal with the tax monster coming to get us all. The current political climate hasn’t helped, with all the misleading claims and misinformation that accompany it.

I’ve already discussed several key components of the retirement tax puzzle: Required Minimum Distributions (RMDs), Qualified Charitable Distributions (QCDs), charitable giving strategies, and the changes introduced by the 2025 “One Big Beautiful Bill” Act (OBBBA), as well as how I’ve implemented them.

Each of those topics stands alone, but when we bring them together, in different retirement-life-stage contexts, we get a powerful picture of how retirees can navigate their situation wisely and use the tax code to their advantage, which I consider part of wise stewardship—giving the government their due and no more.

Jesus said to them, “Render to Caesar the things that are Caesar’s, and to God the things that are God’s.” And they marveled at him. (Mark 12:17, ESV)

I’m describing what is known as “tax arbitrage,” which means managing your current and future years’ income by leveraging the federal tax code’s progressive tax rates to minimize the total tax you pay over your lifetime.

Many retirees are pleasantly surprised to find that a larger portion of their income is tax-free and that their overall tax bill is much lower than they expected. So, while concerns about taxes in retirement aren’t “much ado about nothing,” neither are they something to lose a lot of sleep over—income taxes probably won’t be the thing that wrecks your retirement plan.

As I wrote in an article titled, “25 Things Retirees Tend to Worry About . . .”,

Don’t worry if you didn’t convert everything to a Roth IRA. You’ve likely made the right choice if you’ve evaluated your tax situation and based your decision on fact, not emotion. Yes, tax rates may be higher in the future, but that doesn’t mean YOUR tax rate will be higher—that depends on your income (and its sources), not just what the tax rates are. Even if taxes are higher, you could be in a lower bracket. And your average (effective) tax rate in retirement will almost certainly be less than your marginal bracket when you were working and making pre-tax contributions.

If you’re 65 or older—or approaching that age—this is where all the pieces start to come together. What seems like an unintelligible jumble of rules, exceptions, and acronyms actually reveals a relatively hidden reality: most retirees will pay taxes at lower effective rates in retirement than they did during their working years. That guides almost everything I’ll cover in this article.

Unjumbling the jumble

Regardless of which stage of retirement you’re in, the income you have to spend (your “net retirement income”) can be derived with a long but uncomplicated mathematical formula:

Net Retirement Income = (Social Security + Pensions + Traditional Withdrawals/RMDs − QCDs + Roth Withdrawals + Work Income + Taxable Withdrawals + Interest + Dividends) − (Healthcare* + Taxes)

(*Healthcare refers to the “above-the-line” deductions from Social Security for Medicare Part B. It would also include any Part C Medicare Advantage premiums or Medicare Supplemental coverage you are paying for, plus all other out-of-pocket charges.)

Since we are primarily focused on “taxes,” which reduce “net retirement income” in the above formula, here’s the one for that:

Taxes = (Taxable Income − Standard Deduction − Additional Deduction (Seniors) − Bonus Deduction (Seniors) − Charitable Contributions (Cash)) × Effective Tax Rate*

(*”Effective Tax Rate” is the same as “average tax rate,” which would typically be lower than your “marginal tax rate.”)

It’s easy to see that the more you can save on taxes, the higher your expendable retirement income will be.

Bringing it all together

Let’s look at how your tax (and therefore, your income) situation changes as you progress through each of the following retirement stages.

- Ages 66–69 (Early Years): Individuals who retire at Medicare eligibility age (65) may try to avoid initiating Social Security or withdrawing funds from their taxable retirement accounts, instead relying on other income sources. Effective tax rates may be lower than in their working years.

- Age 70 to RMDs (73 or 75): If delayed until age 70, Social Security benefits begin (there is no reason to delay past age 70), but effective tax rates often remain relatively low. QCDs, which can be started at age 70½, are a significant benefit here, as they reduce taxable income and promote generosity.

- RMD Years (73 or 75+): Effective tax rates often remain favorable, even with larger RMD withdrawals, compared to working-year marginal rates. Reinvest unneeded RMDs wisely.

- Widow/Widowerhood (Any age, but typically 80s or 90s): Taxes can increase, but lifetime planning often still shows a clear win (i.e., lower net taxes paid over a lifetime) for traditional account contributions when working, especially for higher-income earners.

Early stage (ages 66–69)

Early-stage retirees may start withdrawing funds from non-retirement taxable accounts, which may offer favorable capital gains tax rates, and continue doing so until they have exhausted those resources. From that point on, they’ll be drawing mainly from traditional IRAs and 401(k)s. At first glance, you might respond with, “yes, and it’s all taxable as regular income.”

And, you’d be partially correct; it’s all potentially taxable, but as you’ll see, that doesn’t mean they’ll actually pay taxes on it.

Here’s why: federal tax law provides a cushion. Even if your traditional IRA distributions are technically taxable, a large chunk of that income can be offset by the standard deduction and, thanks to the OBBBA, the new senior deduction. When you stack these together, you may discover that a sizeable portion of your “taxable” distribution, or perhaps all of it, isn’t taxed at all.

You can see how the math works based on the “taxes” formula from earlier:

Taxes = (Taxable Income − Standard Deduction − Additional Deduction (Seniors) − Bonus Deduction (Seniors) − Charitable Contributions (Cash)) × Effective Tax Rate1

The formula shows that because of all the taxable income reductions (shown as negatives in the formula), you could end up paying little to no income tax on it. (Functionally, it behaves just like a Roth withdrawal—the IRS never touches that chunk of income.)

Let’s make this concrete. A married couple, Pete and Gladys, turns 66 in 2025.2 They retire but decide to delay Social Security until age 70. They have no taxable non-retirement accounts, so they withdraw $80,000 from their traditional IRAs. They make a $5,000 contribution (non-QCD, as they’re not yet age 70½) to their church. Their simple taxable income calculation using our formula would be:

$80,000 – ($31,500 + $1,600 + $1,600 + $6,000 + $6,000 + $2,000) = $31,300

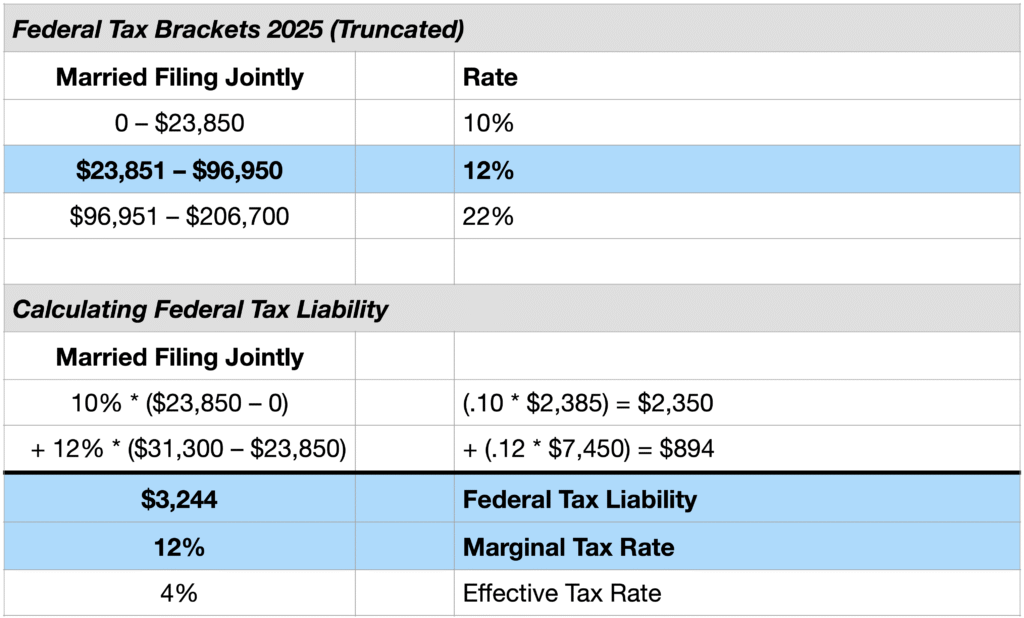

Imagine that! Over 60 percent of their IRA withdrawals ($48,700) are not subject to federal income tax. Their taxable income is $31,300, and although their marginal tax rate is 12%, they have an effective tax rate of only 4%:

Pete and Gladys could have started receiving Social Security benefits and withdrawn less from their traditional IRA. Their tax rate would have been even lower since a percentage of their Social Security income would have been non-taxable. However, they would lose the ≅ 8% annual increase in their Social Security income if they delay until age 70.

No matter what, the generous tax deductions extended to seniors create room for virtually tax-free traditional account distributions during the “Golden Years” of ages 66–69. (As I showed in a previous article, a retired couple with income of $77,045 from IRA withdrawals and Social Security who take the standard deduction, including the new “bonus” deduction, and make the maximum deductible charitable contribution, but do not take QCDs, will pay zero taxes! Yes, that’s right—zero!)

Age 70 to RMDs (73, or later, 75)

By age 70, most retirees are receiving Social Security benefits. At this stage, up to 85% of Social Security may be taxable, causing the deduction impact to fade slightly as Social Security income fills the lower brackets (10% and 12%).

As a result, their IRA withdrawals are pushed into higher brackets (e.g., the 22% or 24% range), which reduces the marginal benefit of deductions or makes new withdrawals more costly from a tax standpoint.

But that doesn’t mean their tax situation goes suddenly out of control, especially if you cut back on IRA withdrawals and replace them with Social Security income, keeping your gross income the same. And even if they don’t, their effective rate will be low.

To illustrate, let’s say Pete and Gladys are now 71 years old and require an annual gross income of $100,000 (a $20,000 increase). Social Security provides $52,000 of that, and the rest ($48,000) comes from traditional IRA withdrawals, which is less than what they received in their 60s. Since they’ve reached age 70½, they give $10,000 to their church using QCDs.

We’ll again calculate their taxable income, but this time we have to account for the taxable portion of their Social Security benefits (which is $31,500):

{($48,000 – $10,000) + $31,500} – {($31,500 + $1,600 + $1,600 + $6,000 + $6,000) + $2,000} = $20,000

The result is that $80,000 (=$100,000 – $20,000) of their $100,000 in gross income is non-taxable. They effectively pay zero tax on their entire Social Security benefit of $52,000, and in addition, only $28,000 of their $48,000 IRA withdrawal is taxable.

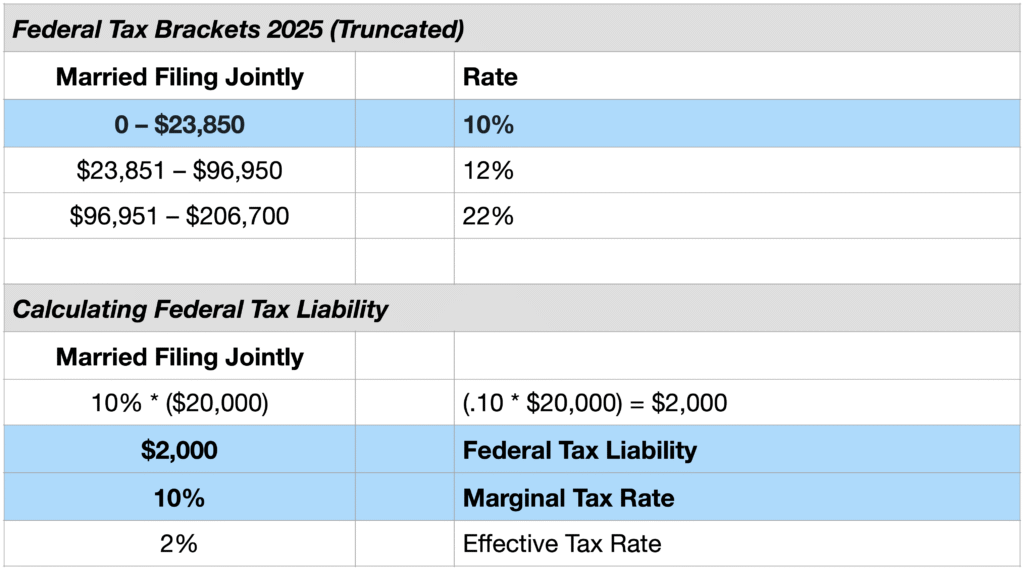

Their QCD reduces taxable income and future RMDs (the next stage of retirement life). Their marginal tax rate is 10% and the overall effective tax rate on $100,000 of gross income is just 2%:

Hard to believe, but the numbers don’t lie.

The key takeaway from this is that adding Social Security to the mix doesn’t have to be a tax disaster. With QCDs and a thoughtful withdrawal plan, many retirees can still achieve tax rate arbitrage – deducting contributions at a rate of 24% or 32% while working and then withdrawing later at a rate of 10% or 12%. I discovered this for myself and discussed it in a previous article, after wondering for a long time if I had made a mistake by not saving much in a Roth account while I was working.

Now let’s move to the next life stage and see what happens when we add RMDs to the mix.

RMD Years (73 or 75+)

For those born before 1960, RMDs now start at age 73. Those born in 1960 or later have to start RMDs at age 75. I’m in the first category, and I have been surprised to find that even larger traditional IRA distributions are still taxed favorably. They’re not the catastrophic tax event we so often hear about in the popular financial media.

To illustrate, we again pay Pete and Gladys a visit. Their traditional IRA has been growing despite starting withdrawals at age 65, and it’s now worth $1.5 million. Let’s pretend it’s 2033 and Pete and Gladys are both 79 years old. They started receiving RMDs at age 75, but are now taking annual RMDs of approximately $85,000 (5.7%).

Additionally, they receive $60,000 per year in combined Social Security benefits (of which $51,000 is taxable). They give $15,000 annually to their church directly from their IRA using QCDs, which counts toward their RMD but doesn’t show up as taxable income. They also make out-of-pocket charitable contributions of $2,000.

{($85,000 – $15,000) + $51,000} – {($31,500 + $1,600 + $1,600 + $6,000 + $6,000) + $2,000} = $72,300

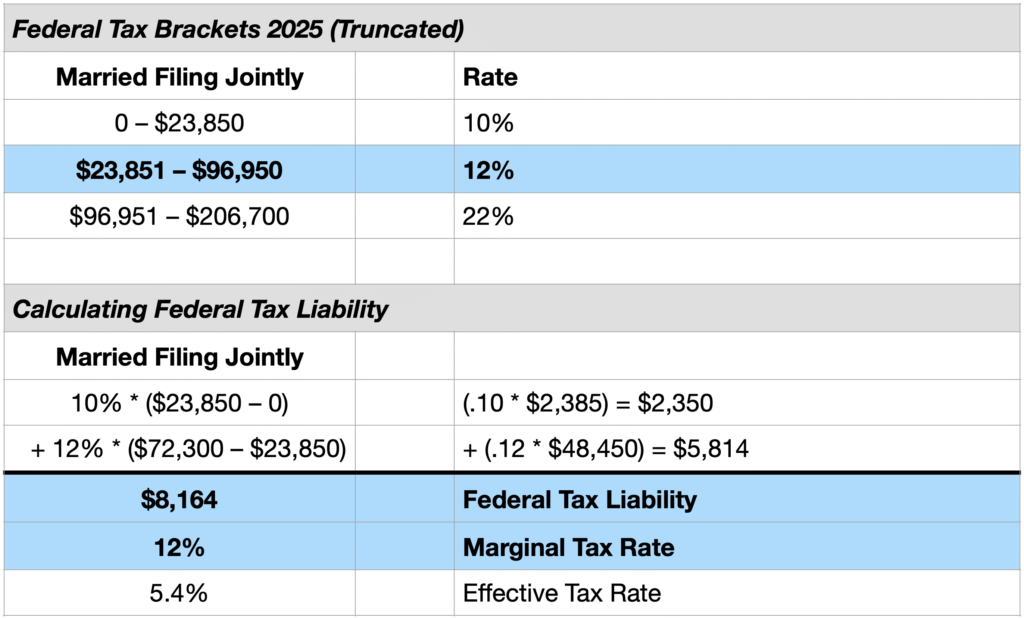

After subtracting all their deductions, including QCDs, their taxable IRA income is $72,300. Their effective federal income tax rate is only about 5.4%:

So, even though their account is large and their RMDs are significant, Pete and Gladys are still paying taxes at a rate far lower than the 24% marginal bracket they were in when they contributed to their 401(k)s during their working years. They’re giving through QCDs, which significantly lowers their taxable income; their standard and senior deductions help even more, and their Social Security is only 85% taxed.

In other words, they’re still winning the tax-arbitrage game in their late 70s, as would anyone who contributed to tax-deferred retirement plans during their working years at higher marginal tax rates.

And if they don’t need all of their RMD for spending? They can reinvest it in a taxable brokerage account, ideally in tax-efficient funds that generate qualified dividends.

The widow(er) years

This last one won’t be as much fun to discuss, but it deserves special attention. I’ve counseled with widows (no widowers as yet) in my church and elsewhere over the years, and I’ve become all too aware of the significant tax implications of widowhood, in addition to the other financial challenges that can come up.

This has been called the “widow’s tax trap,” which is when a surviving spouse must file as a single taxpayer with the same or less income, typically due to the loss of the spousal Social Security benefit and perhaps a pension. That can result in higher tax rates, which can translate into even less income.

Important note: Surviving spouses can file as a “Qualifying Surviving Spouse” (QSS) for the next two tax years after their spouse’s death if they have a dependent child living with them, they paid over half the cost of maintaining that home, and they haven’t remarried.

That status uses the same tax brackets and standard deduction as Married Filing Jointly, effectively continuing the “married filing jointly” benefit for two years.

If they don’t qualify as a surviving spouse (for example, their spouse died more than two years ago), but still have a dependent, they may be able to file as Head of Household if they’re unmarried (or “considered unmarried”) and paid more than half the cost of maintaining a household for a qualifying person (usually a child or sometimes a dependent relative).

If they have no dependents, then they must file as Single, and that’s when the tax hit comes.

It’s 2044, and, sadly, Gladys is now widowed at 84. She has $1.8 million in IRAs, but she faces higher tax rates than she and Pete enjoyed together. (But the good news for Pete—there are no taxes in heaven, as far as I know).

Gladys’ RMD is now approximately a whopping $107,000! That seems like a huge number, but with 2% annual inflation, $107,000 in 2044 has the same purchasing power as about $60,000 today. In other words, what appears to be an enormous RMD is actually just the future version of what would be a middle-income withdrawal today.

I ran the numbers, and I won’t list them in detail again, but when Pete was alive, their effective tax rate was a little over 5%. As a widow, Gladys’ effective tax rate rises to ~12%. That’s more than double her federal tax burden, even though her overall resources haven’t increased commensurately (although some expenses may have decreased).

The “trap” isn’t that Gladys is now “losing” a lifetime of tax arbitrage—she’s still ahead compared to the 24%+ marginal rate of their working years. It’s that, after decades of relatively low taxes together, widowhood shifts her into higher brackets simply because she’s filing as single.

So, we need to maintain some perspective here. During their decades together, they benefited enormously from traditional account deductions and lower effective tax rates in retirement. By the time Gladys files as a single taxpayer, the lifetime tax arbitrage story is still overwhelmingly positive.

Still, I’ve come to realize that widowhood requires careful planning—especially with QCDs and beneficiary designations, and possibly some Roth conversions if they make sense—but it doesn’t overturn the central thesis that for most retirees, taxes are not something to worry too much about.

What about the future?

These articles on taxes in retirement have hopefully given you a much better understanding of how taxes and, especially, how tax “arbitrage” can work in your favor.

Many people worry about future retirement taxes. They worry about politicians changing the rules and about being punished by the government for saving too much. There are concerns, of course, (especially when it comes to the national debt).

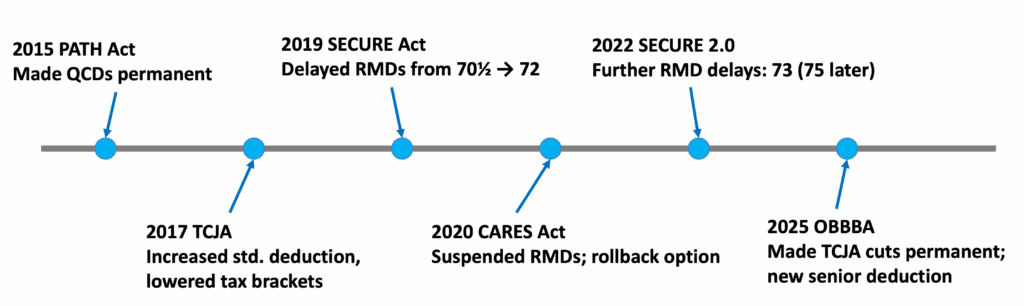

Still, history, demographics, politics, and the current laws all suggest that retirees need not be too concerned. If the past is precedent, retirees are a politically protected group, and their effective tax rates are often surprisingly low.

The graphic below illustrates the major tax laws that have been favorable to seniors, which have been enacted in the last 10 years or so and have largely remained in effect:

Does that mean you’ll pay zero tax forever if you pay none today? Or that all the senior deductions we now enjoy will last forever? Not necessarily. However, it does mean that with planning—utilizing taxable accounts wisely, Roth IRAs, QCDs, Social Security timing, and the generous senior deductions—you can significantly reduce your lifetime tax burden.

If you need help with this (many retirees will), work with a trusted advisor, such as a CFP or CPA,3 who shares your stewardship values. (Most portfolio advisors/managers are not tax experts.)

Ultimately, the goal isn’t just to minimize taxes. It’s to be a faithful steward of what God has entrusted to you—to provide for your family, give generously, and live wisely. The things we’ve discussed aren’t loopholes; they’re tax provisions that favor retirees that can that can be used to help you align your financial reality with your spiritual priorities.

Retirement taxes may look complicated, but when you zoom out, the story is clear: most retirees will pay lower effective rates than they did while working, and they can structure their income in ways that support generosity and stewardship along the way.

That’s good news, and worth sharing with others who may be overly anxious about the tax side of retirement.

For God gave us a spirit not of fear but of power and love and self-control. (2 Tim. 1:7, ESV)

- This formula includes the additional deductions for seniors that were enacted as part of the “OBBBA” of 2025. ↩︎

- The “real” Pete and Gladys would actually be over 100 years old in 2025. They were the couple on an American television sitcom I used to watch as a child. It starred Harry Morgan (also starred in MASH and Dragnet) and Cara Williams. The show aired on CBS every Monday at 8:00 pm Eastern and Pacific time for two seasons, beginning on September 19, 1960. The last episode was broadcast on September 10, 1962. It was hysterical, at least to an 8-year-old! (Source: Wikipedia) ↩︎

- A Certified Public Accountant (CPA) focuses on accounting, tax preparation, and auditing, while a Certified Financial Planner (CFP) specializes in creating comprehensive financial plans, including investments and retirement strategies. Both certifications require passing exams and meeting specific educational and experience criteria. CPAs would be considered “experts” on taxes, while CFPs will possess more general knowledge. ↩︎